По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

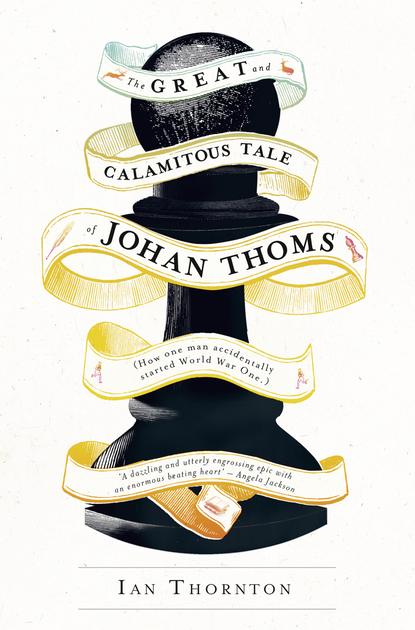

The Great and Calamitous Tale of Johan Thoms

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Johan had started to piece together his own proposition for the nature of things. He had learned at school that humans breathed out just enough carbon dioxide to feed the trees, which in turn returned just the right amount of oxygen for humans. Then there was the sun, which was just far enough away to keep him warm and to grow crops, and to give the world light for enough time to do work and have a bit of play before proffering the night, which loaned just enough darkness to allow sleep, for tomorrow’s energy. If the sun were any closer, life would not be possible; any farther away, he would freeze. There was just enough food on the table for when he was hungry, and if he was thirsty, there was stuff he could pour into his mouth to quench his thirst. If he was cold, there were clothes or a fire, and there was ice for a hot day. He had a soccer ball or a chess set when he was bored. There were those injections and white tablets for when his head hurt. There had been horses to take men around, and now there were engines and automobiles to do it as well. There seemed to be someone for every job. Everything just seemed to work, but was its sheer brilliance by divine design? Or, more likely, was it just too marvelous to have been designed? He started to suspect, with increasing evidence, the latter.

And here were these wonderful women in starched white who would give love and comfort to those with little love and no comfort. He presumed that there were just enough of these generous girls, spread around the globe the right distance apart, that he would never be alone with his pain and would always be clean, surrounded by caring faces and by loving hands, which would put him back together again. The scattering of these angels meant that everywhere had just enough and they were not in excess or shortfall in any one location. The pieces of life’s jigsaw seemed to fall into place, so well designed that there could not possibly be a God who could be doing this. It was just too big a job.

He considered infinity in the other direction, to the smallest particle. If x was an atom, y, cosmic vastness, and z, time, it was just too much. It was miraculous in its nature, in its randomness, in its nondesign. Just one huge coincidence that all seemed to work. From the nurses and their love, he extrapolated a theory that explained everything. It was naive and juvenile (he was just a small boy), but also incredibly neat and real.

The Universe (and everything in it) had been arrived at simply by a series of coincidences—good luck and bad luck, and nothing more. He was convinced of what Caesar had once suspected: that the skies had endured for whatever reason, but that his own future was yet to be determined. His path was in the palm of his own hand. Johan gave God zero credit for life’s canvas and no credit for the oils, which he dreamed of using sometimes liberally, sometimes sparingly, to create a busy yet beautifully arced masterpiece. He would attempt to be measured in his decisions, for he knew that statistics would always be lurking, and would likely kick the fool in the shins. So, having thanked coincidence for delivering him to his current coordinates, Johan would now aim, within the parameters of reason, mathematics, and statistics, to be the Caesar of his own fortunes.

He pondered that he had used up so much of his good luck in surviving a bladed antler in the skull that, if he were to ever again have such a close scrape with death, he would have to run and run and run. He imagined it to be the equivalent of having used up eight feline lives in a single incident. Right now, though, he was grateful to be alive, for he knew that there was no one waiting for him on the other side of that white light.

And so Johan Thoms became Europe’s youngest atheist.

“Does all that God nonsense make sense to you, Dad?” he groggily asked Drago.

“I know, son. It’s like a blind man in a dark room looking for a black cat which isn’t there, but still finding the thing!”

Johan explained his theory of the Universe, which he had dubbed the Immoral Highground, to his father. Drago was proud.

Four (#ulink_51a4437b-63c0-5753-9659-e8db2a8a7994)

The Butterflies Flutter By (#ulink_51a4437b-63c0-5753-9659-e8db2a8a7994)

Happiness is like a butterfly, which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne

My schooldays! The silent gliding on of my existence, the unseen, unfelt progress of my life, from childhood up to youth. Let me think, as I look back upon that flowing water, now a dry channel overgrown with leaves, whether there are any marks along its course, by which I can remember how it ran.”

“David Copperfield?” Ernest asked.

“But of course. Who else?”

* * *

September 1901. Argona.

For a few weeks, Johan lived out the role of minor local celebrity. The bandages came off layer by layer, ultimately revealing a rather normal, if not very lucky, stitched-up young boy. After the interminable summer holiday, he returned to school.

Clusters of children flocked reluctantly to the crumbling schoolyard each morning—less like bees to honey, and more like a hefty trawl of kicking fish. Their uniform khaki trousers and steel-gray shirts sensibly replaced the bleached white of the spring term. With the gray shirts came the unmistakable September nip in the air, and the butterfly nerves of the new term.

Johan had to endure a barrage of teasing about his talking to animals rather than the respect he might have thought he deserved for cheating death, saving the hospital, and becoming friends with European royalty all in one fell swoop.

He would tag along with groups of other boys in the local park, invariably in their wake. The comforting ringing of sublime church bells nearby was enough to send Johan into a deep trance. By the time he would come around, he would find his supposed friends a distant memory, just a small puff of dust where they had stood. He would hear the distant echo of muffled laughter disappearing into the labyrinth of back alleys before he wandered off by himself, seemingly untroubled but still breathing too fast for his own good.

In his solitary walks, he got to know the town by heart. He became a flâneur. Argona was an archaic wonderland, and a safe place in which to grow up. Even the stray dogs bounced around worry-free. Side streets and alleyways, where the bells squeezed and resonated, were wedged between buildings which looked as if they had been there forever. The gargoyles, which seemed to have come straight from a tale by Edgar Allan Poe, glared and spewed not just from towers and eaves, but on door knockers, too, and were carved into the white stone itself. Though supernatural, they lacked any sort of actual threat. Even the abundant ghost stories carried no horror, nor bore any malice.

Argona’s centerpiece was a church dating back to the fourteenth century. Although the cloisters had been destroyed by fire (allegedly during an almighty scrap between God and Lucifer in the fifteenth century), the church had made Argona an important trading center, and it remained a magnificent structure. The rest of the town’s architecture slipstreamed in its former glory.

Old men, when they were not riding through town on trusty, rusty bikes, waited for the last train in faded suits with small trunks. Others sat on the benches around town, considering the club of other old guys doing the same for thousands of miles in every direction. They sat alone, or with a contemporary or a grandson, to whom they repeated exaggerated tales.

In the mornings, the smell of the town’s two bakeries pervaded avenue and nostril. The smells of the late afternoon were of steaming vegetables, infused with roasting meats and paprika from open windows. The Pavlovian clink of cutlery made the children’s mouths water.

The long Argona days gave way to nights of dimly lit taverns, couples kissing in the alleys, and wet cobblestones, to be steamed dry by the morning sun. There was none of the danger of the big city, and if that left the locals a bit naive, then they were more than a little happy. There was an honesty and refreshing plainness to the people, and pretentions were spotted sooner than a degenerate, hungover Austrian count with his fly down.

February 12, 1907

It was his thirteenth birthday, and in the morning he had been playing chess against himself, thinking of talking to deer real or imaginary, and pressing his nose into English literature. Yet he had been unable to fully relax.

He spent his birthday afternoon on his language homework, a thousand words on any subject he chose. He was racking his brains for inspiration, and repeatedly kicking his ball around the garden, when two turquoise butterflies playing tag flew past his nose. He went inside, picked up a pen, and began to write.

One amazingly beautiful creature, many different, unrelated names in different languages, words, all equally charming in their ability to describe it, and all so VERY different.

Mariposa, papillon, butterfly, Schmetterling, borboleta, farfalla, babochka, kupu kupu . . .

The butterfly may well be unique in this characteristic on the planet—not just in the animal kingdom, but in the sphere of the spoken word, Johan Thoms said to himself. He said many things to himself, for his father had taken him to one side as a boy, and with a seriousness Johan could measure in his mind, told him that the man who shows off his intelligence without justification is the same braggard who boasts of the size of his prison cell.

A trawl of Johan’s university library years later would reveal that of the four hundred languages sourced there, no two words for “butterfly” bore any resemblance to each other, not even in such close cousins as Spanish and Portuguese.

“The only commonality is in repeated syllables, meant perhaps to display the symmetry of that fine creature. In Ethiopian, he is the birra birro, in Japanese, the chou chou, and among the Aborigines either the buuja buuja, the malimali, or the man man.” (A very young Johan Thoms made this observation way before a certain Mr. Rorschach thought about boring us rigid with his diagram.)

Johan noted, too, that butterflies always seemed to be around whenever he thought of them. He entitled the essay “The Butterflies Flutter By.”

He was a weird little lad. And, without doubt, a time bomb.

Part Two (#ulink_efa7fbc5-bf2b-5e96-8680-aa7e6d030224)

Remorse, the fatal egg by pleasure laid.

—William Cowper

One (#ulink_34064076-2012-5c5c-96dc-9561efbc98cf)

Fools Rush In (#ulink_34064076-2012-5c5c-96dc-9561efbc98cf)

The feeling of friendship is like that of being comfortably filled with roast beef.

—Boswell’s Life of Johnson

September 1912

Johan Thoms packed up his books in Argona. At the age of eighteen, he had been accepted at the University of Sarajevo with the help of a scholarship—a major shaking of the kaleidoscope for young Johan, one might think, but not really. In Sarajevo he was only an hour from his childhood comforts, and he went rushing forward into dusty libraries while clinging to the past, returning at every opportunity to the Womb of Argona (a phrase he also used jokingly to refer to his mother). His determination to enjoy the present seemed to be dogged by his worry about the future and, more specifically, his desire to please his parents. He tried repeatedly to remind himself of his own theory of the Universe, and to live in the present. He tried to tell himself that what was done was done, that what will be was within his own control, and that there was no God to punish him for present, past, or future deeds. Within these seconds, he found peace of mind. However, it would take only somewhere between a fragment of a conversation and the distraction of a passing sparrow to lead his mind astray, and he would have broken his calming promise to himself.

* * *

Chess and soccer finally conceded to books.

Johan’s love of literature had been grounded in summer afternoons in the school glen reading Dickens with his favorite teacher, upon whom he had developed a crush at the age of ten. The class dissected English classics under the apple blossom trees, which in spring were whiter than the students’ bleach-white shirts. Johan was then rarely seen without a scabby novel or a yellowing library newspaper. Often he disagreed fiercely with what he read. When something made sense, he would slowly close his tome, his thumb keeping his spot, and ponder the newly found truth.

In his university years, he adopted the same technique for things with which he did not concur. Finally, differing opinions received more of his attention than those confirming his own often-stubborn beliefs. (Conversely, history professors claim that Pol Pot, Stalin, and Hitler read only books with which they already agreed, giving them an even more distorted vision of the world.)