По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

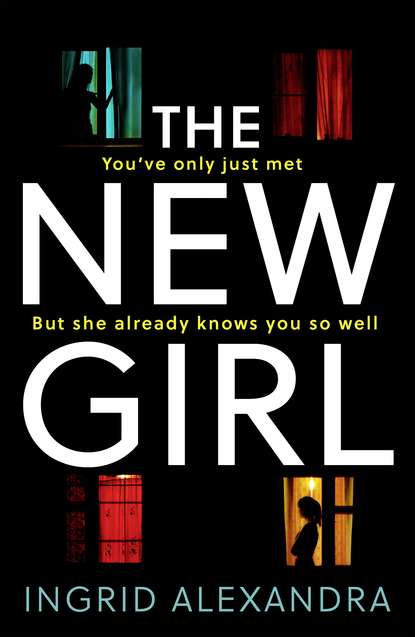

The New Girl: A gripping psychological thriller with a shocking twist perfect for fans of Friend Request

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That’s when my memory gets sketchy. I remember looking at my face in the mirror, seeing irises nearly engulfed by pupils that seemed to pulse as I stared. My face was out of focus, my skin blotchy, unnaturally pale. Someone knocked on the door and, when I turned my head, I saw stars, and then I threw up in the sink until there was red behind my eyelids.

In search of Mark, I followed some people who were making their way down to the beach. But I don’t remember how I got there – there’s another of those blank spaces. Next thing I knew, I was by the shore. There were houses nearby, and I could hear people in the distance. I think they must have been running into the water; I remember silhouettes against a street light, squeals and laughter, and the rumble of the ocean.

I don’t know what happened after that; I must have passed out. Sometimes there are snippets, like the sound of someone yelling, or maybe screaming, a face peering down at me, the ocean whispering its secrets. But mostly, it’s blank.

When I came to, Mark was standing over me shouting, hands gesturing wildly, his eyes crazed and gleaming. He was staring at me, at something near my stomach, but I didn’t know why, and a coil of panic tightened in my gut. When I looked down, all I could see was blood.

It was a while before my senses returned to me. The white noise in my head cleared and I could hear Mark ranting about something, some eight ball I’d supposedly been carrying for him. I had no idea what he was talking about, but he found the drugs in my purse, wrapped me up in his coat and dragged me to the car. As far as we know, no one saw us.

Later, I stood naked in our laundry, my arms crossed over my chest, shivering with disgust and fear as I watched Mark pile our clothes into the washing machine. As he switched it on and it slowly filled up with water, I knew in my bones that the blood turning the soap suds pink wasn’t mine.

Whose it was, and how it got there, I’ll never know.

Once I’d washed myself clean, I lay in our bed, awaiting the inevitable. But it never came. Mark paced the hall – I could see his shadow, hear his drunken muttering above the roar and hiss of the sea. But then he went silent and, not long after, I could hear rattling snores in the living room. He didn’t come to bed, which was strange. I knew my bag was packed and waiting for me if I needed it. But I started having second thoughts.

The next day we heard the news that a guy had been found dead at Dealer Dan’s party. An unemployed twenty-eight-year-old man named Tom Forrester, known to police for drug dealing and petty theft. It was shocking to find out someone had died at a party we attended, possibly while we were there, but I didn’t know the guy so I wasn’t too cut up about it.

It wasn’t until Mark started acting strangely that I began to worry. We’d talked about it once we had sobered up, and Mark had convinced me we had nothing to do with whatever had gone on. The guy was found bludgeoned to death. They think it was a brick, even though they never found the murder weapon. Pretty gruesome. If he was a drug dealer, the most likely scenario was that his death was related to money or drugs. Which was what they ended up suspecting anyway, even though the murderer was never caught. The fact I couldn’t ignore then, and that haunts me now when I trawl through those old newspaper articles, is that Mark had recently lost a lot of money and – I suspected – was dealing drugs again.

Everyone who was at the party was questioned. We waited for days, for weeks, for the cops to arrive, but they never did. We couldn’t guess why, but we considered ourselves lucky.

The blood. Neither of us could account for it. I racked my brain trying to remember details. If I’d seen anything that night, it could have helped with the investigation. I knew I’d headed towards the beach and passed out. I know I woke up with a bump on the back of my head and some bruises on my arms, but nothing more serious than my usual drunken mishaps. Though Mark had been missing and I couldn’t vouch for where he’d been, he told me he was down the road scoring from a mate and, as that was usually the case when he was MIA, I hoped it was the truth.

Mark’s story was that he’d come looking for me after meeting his mate, and that he’d asked around but no one knew where I was. Apparently he saw some guy passed out but thought nothing of it because ‘it was a drug party, for fuck’s sake’. So he went looking down by the beach and found me semi-conscious in a nearby side street. Covered in someone else’s blood. Why was I there? What had happened to me?

He convinced me we had nothing to do with the guy’s death, that it probably wasn’t even the guy he saw. He said I should keep my mouth shut about the blood. It was probably mine, he said, even though there wasn’t more than a scratch on my body. It was on him too, I remember that much, but he claimed it came from me, when he’d carried me to the car. He said that maybe I’d thrown it up or something. It would be stupid to say anything about it, he told me.

I knew he wasn’t saying these things to protect me, like he claimed. He had enough of a record to get in some serious trouble if it was dredged up, so he was protecting himself from further involvement with the police.

I tried not to think about what it meant that Mark would just leave someone in a state like that. The guy was unconscious. Maybe Mark didn’t see the blood – or maybe it wasn’t even Tom Forrester he saw, who knows. But he walked away. He didn’t even try to help. I wanted to scream at him, to get him to look at himself, look at what kind of person he’d become. But, by that stage, I’d learned a few things. And I knew what would happen if I questioned him.

Chapter Eight (#ulink_df33429b-148f-5595-a1fe-b7322671af80)

The sand is gritty and damp between my toes as I pace the beach. It’s late afternoon but the sun is still high and people are swimming, fishing, huddled in groups under beach umbrellas. I’ve always felt a tidal pull towards the sea. A water baby, Mum used to call me. I feel it now, the pull, as though the ocean is calling to my blood.

I spent many summers on the coast with my parents before they disappeared. It’s hard to believe that was five years ago. Something inside me has always known they’re not coming back. Not now, after all this time. And yet I watch the families at play, and hope lingers. Hope dies last, Doctor Sarah says. But that’s not why I’m here, it’s really not. I’m here because I have to be. Doctor Sarah says so.

The ocean is a different colour each day. Today it’s grey-brown, the colour of a puddle after rain. The storms have stirred things up, clouding the water with seaweed and sand. The humid air is ripe with something, perhaps anticipation, another storm on its way, and I’m edgy, unable to shake the feeling I’m being watched.

I push on, forcing one foot to follow the other, ignoring the prickles on the back of my neck. If I don’t do this, I’ve already failed, and I can’t afford that. Doctor Sarah says it’s a measure of my control over my anxiety. If I can manage a walk each day, I’m doing okay. I can feel proud of something. An achievement. Because there’s not much else I’m proud of at the moment.

Children are shrieking and splashing, their browned, skinny bodies darting in and out of waves. A man stands nearby, motionless, facing the sea. Their father, I suppose.

There’s movement in the fir trees lining the surrounding parkland, but when I look, it’s only the branches quivering in the breeze. I close my hand around the device in my pocket. It’s become a comfort thing, clutching it tight, running my fingers over the small, round buttons. It’s a personal alarm, one that cost a small fortune, but it’s worth it. I’ve had it since Aunty Anne started worrying every time I left her sight. Bringing it with me is another of her ‘conditions’ for me moving out. One press of a button and the nearest law enforcement is notified of my location. Someone will come straight away. You can’t put a price on peace of mind, Aunty Anne said. I’m with her on that.

Walking clears my head and most days, after the initial fear, I enjoy it. But today something’s off. I check my phone: no messages. I watch people going about their business: surfers bobbing on the waves, teenagers in school uniform eating burgers and fish and chips outside the kiosk, people strolling after a day’s work, families squabbling and playing. How do they do it? How do they carry on each day, taking care of business, of their families, of themselves? I used to be able to do the same. I went to school, worked weekends at the local café. I had a family …

I plug my mouth with a finger and bite down until I feel the familiar pain. Step after step, breath after breath, I come to the curve in the bay where the water is shallow. This is the spot. A few more metres and I can turn back, my day’s quota done.

A heavenly beam of light has burst through the low clouds, illuminating each wave and ripple on the water’s surface. There’s a houseboat floating a few metres from the shore, a dilapidated-looking thing, mostly wood with peeling white paint, a blue stripe around its perimeter, little round windows in the cabin below its bow. I must have seen it before; those little windows seem familiar. I imagine peering out of them, watching the waves roll past. What would it be like to live on the sea, sailing away whenever you please?

My throat feels dry and I recall the bottle of wine I sneaked into my room last night. It’s about time to replenish, so I opt out of walking the last few metres and head back to the apartment.

In the kitchen, Cat’s washing up and sipping from a glass of wine. Perfect. I’d forgotten it’s Friday – there’ll be no hiding tonight.

She smiles at me over her shoulder. ‘Hey, you! Nice walk today?’

‘Yeah, it was fine.’

Cat nods at her wine glass. ‘The rest of the bottle’s chilling in the freezer. Mine’s warm, I’m afraid. I couldn’t wait.’ She grimaces as she sips.

‘Bad day?’ I open the freezer and help myself to the wine.

‘You have no idea. Gia’s been bawling to me again and I’m like, I already told you! Ben’s just not …’

‘Ben’s just not what?’ a voice says from behind us.

Cat winces but then breaks into a giggle as Ben stands in the hallway, scratching the hairy, tanned flesh exposed between his shorts and T-shirt.

‘Have you been napping this whole time?’ she asks.

‘Yeah. Have you been talking about me this whole time? What am I “not”?’

Cat exhales through her nose. ‘Gia thinks you two are dating and I keep telling her you’re not interested.’

‘Who says I’m not?’

‘Um, you do. You say it all the time!’

‘I’m interested in certain parts of her …’

‘Ugh. Ben, you just …’

‘I was talking about her brain!’ Ben laughs. ‘I’m just not … you know. Into her like that.’ He turns to me and grins.

‘Then you need to fucking tell her, you idiot,’ Cat snaps. ‘I’m sick of her just showing up here.’

Watching them, I feel suddenly tired. I pick up my glass and go to the couch, start scrolling through my emails. There’s a Facebook notification from a name I don’t recognise. Jake Morns.

Without thinking, I click on it.

I will find you.

My blood turns to ice. The wine glass trembles in my hand as the familiar panic rises. I set the glass down on the coffee table and bite down hard on my lower lip. What was I thinking? I should have known better than to believe blocking Mark’s email would work. This is him, it has to be. There’s no picture, of course, just the little blue thumbnail with a blank face. Jake Morns. Yup. I rearrange the letters … Mark Jones.

Saliva sticks in my throat. I close my eyes, and Mark’s face appears. And then another image comes, as clear as day.

Mark’s mouth, a gaping black hole, open in a scream. Eyes like brimstone under the street lamp, a voice yelling ‘Run!’ and a name, but I don’t catch it. The waves are growling in the background, it’s hard to hear. I’m on the ground near a low wall, shivering though it’s not cold. Mark’s crouched on the ground. He’s holding something, something with sharp edges. Something wet and gleaming.