По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

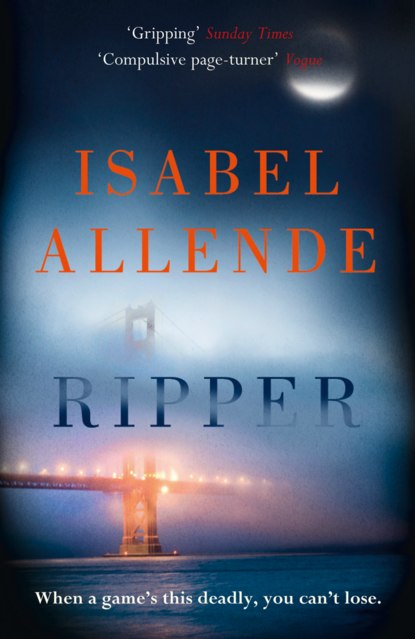

Ripper

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Since the first visit the previous November, Indiana had used a variety of approaches with scant results, and she was beginning to lose heart. He insisted that the sessions with her relieved his pain, yet still she could visualize it with the certainty of an X ray. Believing as she did that wellness depended on a harmonious balance of body, mind, and spirit, and unable to detect anything physically wrong with Gary, she attributed his symptoms to a tormented mind and an imprisoned soul. Gary assured her that he’d had a happy childhood and a normal adolescence, so it was possible that this was related to some past life. Indiana was waiting for the opportunity to delicately broach the idea that he needed to cleanse his karma. She knew a Tibetan who was an expert on the subject.

Indiana realized from the start, before Gary even uttered a word at his first session, that he was a complicated guy. She could sense a metal band pressing in on his skull and a sack of stones on his back: the poor man was carrying around some terrible burden. Chronic migraine, she guessed, and he, astonished by what seemed like clairvoyance, explained that his headaches had grown so bad over the past year that they made it impossible for him to continue his work as a geologist. The profession required him to be in good health, he explained; he had to crawl through caves, climb mountains, and camp out under the stars. At twenty-nine years of age, he had a pleasant face and a puny body, his hair cropped short to disguise his premature baldness and his gray eyes framed by thick black glasses that made him seem insipid. He came to Treatment Room 8 every Tuesday, always arriving punctually, and if he was particularly in need, he would request a second session later in the week.

He always brought Indiana little gifts, flowers or books or poetry. He was convinced that women preferred poetry that rhymed, particularly on the subject of nature—birds, clouds, rivers. This had in fact been true of Indiana before she met Alan, who was ruthless in matters of art and literature. Her lover had introduced her to the Japanese tradition of haiku, particularly the modern variant gendai haiku, though in secret she still enjoyed sentimental verse.

Gary always wore jeans, boots with thick rubber soles, and a metal-studded leather jacket, an outfit that contrasted starkly with his rabbitlike vulnerability. As with all her clients, Indiana had tried to get to know him well so that she could discover the source of his anxiety, but the man was like a blank page. She knew almost nothing about him, and what little she managed to find out, she forgot as soon as he left.

At the end of the session that Tuesday, Indiana handed him a vial of oil of geranium to help him remember his dreams.

“I don’t dream,” said Gary in his taciturn manner, “but I’d like to dream about you.”

“We all dream, but not many people attach any importance to their dreams,” she said, ignoring the innuendo. “In some cultures—the Australian aborigines, for example—the dream world is as real as their waking life. Have you ever seen aboriginal art? They paint their dreams—the paintings are amazing. I always keep a notepad on my nightstand, and I jot down my dreams as soon as I wake up.”

“What for?”

“So I’ll remember them,” she explained. “They can guide me, help me in my work, dispel my doubts.”

“Have you ever dreamed about me?”

“I dream about all my patients,” she said, ignoring the implication once again. “I suggest you write down your dreams, Gary, and do some meditation.”

When he first came, Indiana had devoted two whole sessions to teaching Gary about the benefits of meditation, how to empty his mind of thoughts, to breathe deeply, drawing the air into every cell in his body and exhaling his tension. Whenever he felt a migraine coming on, she suggested, he should find a quiet spot and meditate for fifteen minutes to relax, curiously observing his own symptoms rather than fighting them. “Pain, like our other feelings, is a doorway into the soul,” she had told him. “Ask yourself what you are feeling and what you are refusing to feel. Listen to your body. If you focus on that, you’ll find that the pain changes and opens out inside you, but I should warn you, your mind will not give up without a fight; it will try to distract you with ideas, images, memories, because it’s happy in its neurosis, Gary. You have to give yourself time to get to know yourself, learn to be alone, to be quiet, with no TV, no cell phone, no computer. Promise me you’ll do that, if only for five minutes every day.” But no matter how deeply Gary breathed, no matter how deeply he meditated, he was still a bundle of nerves.

Indiana said good-bye to the man, listened as his boots padded down the corridor toward the stairwell, then slumped into a chair and heaved a sigh, feeling drained by the negative energy that radiated from him, and by his romantic insinuations, which were beginning to seriously irritate her. In her job, compassion was essential, but there were some patients whose necks she longed to wring.

Wednesday, 11 (#ulink_9540f5dc-0806-5c74-87af-26e080d814fb)

Blake Jackson received half a dozen missed calls from his granddaughter while he was running around like a lunatic after a squash ball. After he had finished his game, he caught his breath, showered, and got dressed. By now it was past nine at night, and his buddy was hungry for Alsatian food and beer.

“Amanda? That you?”

“Who were you expecting? You called me!”

“Did you call?”

“You know I called, Grandpa, that’s why you’re calling me back.”

“Okay, jeez!” Blake exploded. “What the hell do you want, you little brat?”

“I want the lowdown on the shrink.”

“The shrink? Oh, the psychiatrist who was murdered today.”

“It was on the news today, but he was murdered the night before last or early yesterday morning. Find out everything you can.”

“How am I supposed to do that?”

“Talk to Dad.”

“Why don’t you ask him?”

“I will, as soon as I see him, but in the meantime you could get a head start on the investigation. Call me tomorrow with the details.”

“I have to work tomorrow, and I can’t be calling your dad all the time.”

“You want to carry on playing Ripper or not?”

“Uh-huh.”

Blake Jackson was not a superstitious man, but he suspected that the spirit of his late wife had somehow managed to pass to Amanda. Before she died, Marianne had told him that she would always watch over him, that she would help him find comfort in his loneliness. He had assumed she was referring to him marrying again, but in fact she was talking about Amanda. Truth be told, he’d had little time to grieve for the wife he loved so much—he spent the first months of widowhood feeding his granddaughter, putting her to bed, changing her diapers, bathing her, rocking her. Even at night he did not have time to miss the warmth of Marianne’s body in his bed, since Amanda had colic and was screaming at the top of her lungs. The child’s frantic sobbing terrified Indiana, who ended up crying with her while he paced up and down in his pajamas, cradling his granddaughter while reciting chemical formulae he had learned back at pharmacy school. At the time Indiana was a girl herself, barely sixteen years old, inexperienced in her new role as mother, depressed because she was still as fat as a whale and because her husband was worse than useless. No sooner had Amanda stopped suffering from colic than she began cutting her first teeth; then she had chickenpox, with a burning fever and a rash that extended even to her eyelids.

This levelheaded grandfather was surprised to hear himself talking aloud to the ghost of his dead wife, asking what he could do with this impossible creature, and the answer arrived in the form of Elsa Domínguez, a Guatemalan immigrant sent to him by Bob’s mother, Doña Encarnación Martín. Elsa already had more than enough work, but she took pity on Blake Jackson, whose house was like a pigsty, whose daughter couldn’t cope, whose son-in-law was never there, and whose granddaughter was a spoiled crybaby, and so she gave up her other clients and devoted herself to this family. From Monday to Friday, while Blake Jackson was working at the pharmacy and Indiana was at high school, Elsa would show up in her clapped-out car, wearing sweatpants and carpet slippers, to impose order on the chaos—and she managed to transform the screaming ball of fury that was Amanda into a more or less normal little girl. She talked to the child in Spanish, made sure she cleaned her plate, taught her to take her first steps and, later, to sing, to dance, to use a vacuum cleaner and lay the table. On Amanda’s third birthday, when her parents finally separated, Elsa gave her a tabby cat to keep her company and build up her strength. In her village in Guatemala, she said, children grew up with animals, they drank dirty water, but they didn’t get sick like Americans, who succumbed to every germ that came along. And her theory proved to be correct; Gina, the cat, cured Amanda of her asthma and her colic.

Friday, 13 (#ulink_f3a05bd0-a583-5b96-b51c-3a336dded7c5)

Indiana finished with her last patient of the week, an arthritic poodle that broke her heart and that she treated for free because it belonged to one of her daughter’s schoolteachers, who was mired in debt, thanks to her gambling-addict husband. Indiana closed Treatment Room 8 at six o’clock and headed for the Café Rossini, where her father and daughter were waiting for her.

Blake Jackson had gone to pick up his granddaughter from school, as he did every Friday. He looked forward all week to the moment he’d have Amanda as a captive audience in his car, and he would eke out the time by choosing routes where the traffic was heaviest. Grandfather and granddaughter were buddies, comrades—partners in crime, as they liked to say. They talked on the phone almost every day the girl spent at the boarding school, and made the most of any spare time to play chess or Ripper. They talked about the tidbits of news that he passed on to her, with the emphasis always on the oddball stories: the two-headed zebra born in a Beijing zoo; the fat guy from Oklahoma suffocated by his own farts; the mentally disabled people who had been kept locked in a basement for years while their captors collected their social security. Recently, their talk had been only about local crimes.

When she got to the café, Indiana noticed with a disapproving glance that Blake and Amanda were sharing a table with Gary Brunswick—the last person she expected to see sitting with her family. Coffeehouse chains had been banned in North Beach to save local businesses from a slow death, to stop the character being sapped from Little Italy—so it was still possible to get excellent coffee at a dozen old-fashioned spots. Neighborhood residents would choose a café and stay loyal to it; it was part of their identity. Gary didn’t live in North Beach, but he had stopped by the Café Rossini so often recently that they already thought of him as a regular. He spent much of his spare time hunched over his computer at a table by the window, not talking to anyone except Danny D’Angelo, who—as he admitted to Indiana—flirted shamelessly with Gary just to enjoy the look of terror on his face. He liked watching the guy shrink with embarrassment as Danny put his lips to his ear to ask in a lewd whisper what he could get him.

Danny had noticed that whenever Gary was in the café, Indiana drank her cappuccino standing by the bar and left in a hurry. She didn’t want to offend a patient by sitting at another table, but she didn’t always have time for a proper conversation. In any case they weren’t conversations so much as interrogations, in which Gary bombarded her with inane questions and Indiana answered distractedly: she’d be thirty-four in July; she’d been divorced at nineteen; her ex-husband was a cop; she’d once been to Istanbul and had always wanted to go to India; her daughter Amanda played the violin and wanted to get a new cat because hers had died. Gary would listen with exaggerated interest as Indiana stifled a yawn. This man lived behind a kind of veil, she thought—he was a smudged figure in a washed-out watercolor. And now here he was, having a friendly get-together with her family, playing blindfold chess with Amanda.

It was Danny who had introduced them: Indiana’s father and daughter on the one hand, and one of her patients on the other. Gary had figured that grandfather and granddaughter would be waiting at least an hour for Indiana to finish her session with the poodle, and since he knew Amanda liked board games (her mother had told him), he challenged her to a game of chess. Blake timed them with a chess clock he always put in his pocket when he was going out with Amanda. “This girl here can take on multiple opponents at once,” he warned Gary.

“So can I,” said Gary. And sure enough, he turned out to be a much more astute and aggressive player than his timid appearance suggested.

Folding her arms impatiently, Indiana looked around for another table, but they were all taken. In one corner she saw a man who looked familiar—although she couldn’t say from where—with his nose in a book, and asked if she could share his table. The guy got such a fright that he leaped up from his seat and the book fell on the floor. Indiana picked it up: a William C. Gordon detective novel that she had seen among all the books, of variable quality, on her father’s shelves. The man, who was now the beetroot color particular to embarrassed redheads, gestured to the empty seat.

“We’ve seen each other before, right?” said Indiana.

“I haven’t had the pleasure of an introduction, but our paths have crossed on a number of occasions. Samuel Hamilton Jr. at your service.”

“Indiana Jackson. Sorry, I don’t mean to interrupt your reading.”

“It’s no interruption at all, ma’am.”

“Are you sure we don’t know each other?”

“Quite sure.”

“Do you work around here?”

“From time to time.”

They carried on with their small talk while she sipped her coffee and waited for her father and daughter to finish—only a matter of minutes, since Amanda and Gary were playing against the clock. When the game finished, Indiana was shocked to realize that that jerk had beaten her daughter. “You owe me a rematch,” Amanda said a little bitterly to Gary as she left—she was not used to losing.

The old Cuore d’Italia restaurant, established in 1886, was famous for its authentic cuisine—and for the gangland massacre that had taken place there in 1926. The local Mafia had met in the large dining room to taste the best pasta in the city, drink good bootleg wine, and cordially divide up California between them; then one gang pulled out their machine guns and blew the others away. In a matter of minutes twenty capos lay dead, and the place was a grisly mess. Though the distasteful incident was soon just a memory, that had never put off the tourists, who flocked there out of morbid curiosity to sample the pasta and take photos of the crime scene, until the Cuore d’Italia burned down and was rebuilt in a new location. A persistent rumor around North Beach had it that the owner had doused it in gasoline and set a match to it to get back at her cheating husband, but the insurance company couldn’t prove a thing. The new Cuore d’Italia boasted brand-new furniture but retained the atmosphere of the original, with huge paintings of idyllic Tuscan landscapes, painted terra-cotta vases, and plastic flowers.