По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

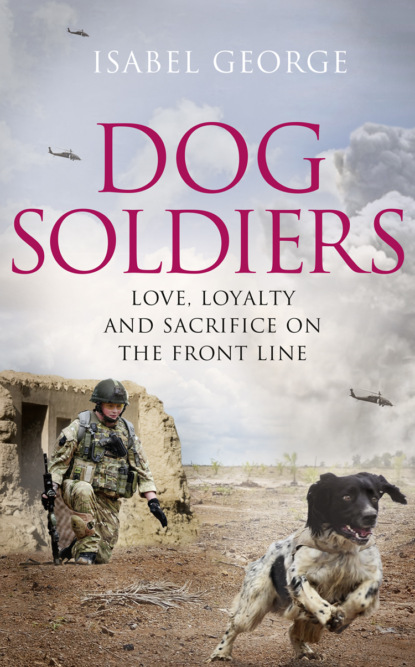

Dog Soldiers: Love, loyalty and sacrifice on the front line

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘As I looked at Ken lying there, I know it sounds odd, but a part of me was relieved that I could honestly tell his mother, when I called her in the next few hours, that he looked as if he was sleeping. As for the rest of it – I could not possibly explain.’

The Union Flag was lowered to half mast at Bastion. Sadly this was something that was happening more often during the summer of Op Herrick 8, but for the men and women of the RAVC’s dog soldiers it was something they hoped they would never see for one of their own during the conflict. They hadn’t lost a dog soldier since The Troubles in Northern Ireland.

‘When a soldier is lost, the flag is flown at half mast and I could not believe that this time it was lowered for one of mine,’ recalls Frank Holmes. ‘I now hate flagpoles. What made it worse was the constant repeats on Sky News, and the added loss of Sasha extended the coverage and the agony for all watching. We thought of Ken’s family, lovely people, who would be mourning their son. Believe me, the grief at Bastion and FOB Inkerman was palpable.’

Martyn Thompson was hearing major concern from the men and women in his command over the retrieval of Sasha. He was able to tell them that he had said, ‘Bring the dog if you can,’ but everyone was fully aware of the risks. The area was crawling with Taliban, making it impossible to return to the site without risking a life or limb. What Martyn and his colleagues didn’t realise at the time was that the men of 2 Para had already made a silent promise to each other that they would reach Sasha – no matter what.

Moving in, under the noses of the Taliban, they lifted Sasha’s body off the road and returned her to Inkerman. They said later that Ken’s dog was regarded in the same way as her handler, as one of their own, and there was no way they were going to leave her alone or where she lay. It was a risky mission; the Paras were aware that the enemy would be watching and expecting the soldiers to return for their dog. For all they knew they could have been walking into an ambush or the body could have been booby-trapped. Undeterred by the obvious risks, the men brought Sasha in and handed her back to her family: the RAVC.

When Marianne and the others heard what the Paras had risked for Sasha, tears flowed: ‘I had been tasked out to an Operation in FOB Gibraltar (FOB GIB), which was 10 to 15 km from where Ken was based at FOB Inkerman. It was known to be a risky area. I was with 3 Para and we were due to go on a task early in the morning. The plan was to leave really early in the morning before the light came up so we could move to positions before the enemy could see us.

‘The helicopter dropped me at FOB GIB and got my admin squared away before we all tried to get some sleep. It was early but we also knew we had to be up early. No surprise that it took me forever to get to sleep. I remember just curling up on the sand with my helmet as a pillow and finally managing to drift off. Ironically, once it was dark someone woke me up and I was like, “Oh, for f***’s sake, it’s time to go already?” But the guy just said, “Boss wants to see you.” Straight away I knew someone had deffo been hurt.

‘So I went. Quickly. “Look, a handler and his dog have been hit.” My body became heavy and my mind raced … Who? What? They said they had little info but it was an RPG attack. I wanted to know who it was.

‘They told me I could go through the sit rep/9 liner (situation report) that had been sent to see if could find a ZAP number. I was scrolling through the whole thing and the first listing that caught my eye was the last four numbers of Sasha’s Service number. I was, like, no f***ing way has she been hit. Then I scrolled down more and more and there it was – confirmed. Then I saw Ken’s ZAP number.

‘At this point I was just skimming. I was sure they were just injured. Then I saw “KIA” in what seemed massive writing. I clocked it again. KIA – Killed in Action. I felt like I had had my guts ripped out completely. I felt so heavy and I really didn’t want to believe it. The guys asked if I was OK and I was like, yeah, and went back to my rock to lie down.

‘I lay there while everyone around me slept. The sky in Afghan is so clear that you wouldn’t believe the amount of stars. Everything seemed silent but at night it was far from it. The noise of the Ops room is usually ongoing and the noise of the bugs and cricket things is like white noise – it’s constant. I was there with around 150 guys but right then it felt like I was just sat in the middle of the desert with absolutely nothing and no one around me. I couldn’t really think straight. I just sat with no thoughts, hearing no noise. Nothing.

‘As I waited to be called to go on task I couldn’t cry. By the time I was called to go on the op, between about 3 and 4am, I was so angry with myself because there was no space inside me to feel pain. I was angry Sasha had gone and I had let it happen and I was angry that I hadn’t shed a tear for my colleague, Ken. My best friend used to always joke and say I had a heart of stone or that I was dead inside and in actual fact I started to believe it at this point.

‘So I got asked if I was still up for going out. I was like, “Yes, of course.” Off I went with my dog, Leanna, on a shit night patrol looking for a bunch of a***holes that had just done this to my mates. I was pretty pissed off by this point but knew I’d keep my head. Looking back, that patrol felt like the longest I had ever done but it was probably the shortest. I had been used to ops lasting weeks out on the ground and this was just 24 hours. The guys had a clear objective and it was due to be a quick in and out job.

‘I can’t remember exactly what we were there to do but we were supposed to get places in the dark without the enemy knowing, but about 5 minutes after leaving the FOB there was radio chat from the enemy – they had pretty much clocked us as soon as we had left. We were rather vulnerable as it was new territory to us.

‘When we returned to the FOB I was told a Sea King hele was on its way for me. I told them I was fine and wanted to continue, but that didn’t work. I was then told the hele was on its way and I would be 100 per cent on it – no discussion. I was so exhausted that I remember rolling into the belly of the big bird and just lying there while it took off. I got dragged into a space and left huddled by mailbags.

‘I honestly can’t remember what happened when I got back to Bastion. I am sure we would have been gathered many times but when they talked it was almost like I was under water and only hearing mumbling. It was difficult. I remembered Ken saying to me that he felt really lucky to have Sasha as his search dog as her performance was of such high quality. He was right, she was the best and I know he looked after her. I couldn’t hug Sasha but I remember going to Leanna and begging a cuddle. I sat with her in her kennel for ages. Poor Leanna did her best to comfort me but I felt so guilty. I had lost Sasha and a good mate but I could not cry.

‘I felt worse when I found out later that Sasha’s body had not made it back with Ken’s but then when I was told about the incredible bravery of the guys of 2 Para who had taken it upon themselves to go on a patrol the next morning to retrieve her it absolutely blew me away that they would consider her so highly that they risked their lives to bring her in. My gratitude to these guys remains endless.’

When Marianne heard that Sasha’s body was due back into Camp Bastion she went to the hele pad to accept her.

‘When I returned to the dog unit I lay her on the cold floor and unzipped her body bag. She lay there, not a mark on her body. She looked, as she always looked to me – perfect. Then I turned her over. There was blood and the wounds were deep, but there’s no way you would think they would be enough to kill her. I guessed the shock would have been too much for her. I took a moment with Sasha and apologised a million times over before saying goodbye.’

The wheels of administration moved swiftly and with every eye on getting it right for the man, but there was also a large swell of feeling in getting it right for the dog, too. After all, they died as they served – together. If Kenneth Rowe was going home then it was the dog soldiers’ wish that Sasha go home too and, more than that, she would join him on the flight back to RAF Lyneham. After a great deal of jumping through hoops and rewriting the rule book it was agreed that Ken and Sasha would be repatriated together.

Time was short. Due to the regulations and the heat, Sasha’s body had to be cremated right away, and in the true tradition of the British Army the minds and skills of everyone pulled together to ensure that this canine hero returned in a fashion befitting her military status. There would be no flag-draped coffin for her, so the armourers pitched in with a 5-inch diameter shell casing, engraved with her name and dates, to hold her ashes. It was finished with a polished-wood stopper and the whole thing gleamed to the point that it made anyone who looked at it blink. It was a fine tribute to a fine dog.

Martyn Thompson and Frank Holmes were in charge of the arrangements for the repatriation of Ken Rowe and Sasha back to the UK, and for Frank the ordeal was nothing short of surreal: ‘Never did I think I would need the repatriation training I received on my drill instructor’s course. To be honest, at that time it was treated with a touch of “gallows humour” at Pirbright (the Army training centre) – one of the guys dressed up as the mum or girlfriend, the chaplain is present and we practised for what seemed like a week for something you think you are never going to do for real. I never thought I would do it in my own unit. But there we were, with just two days to get it right for Ken and now Sasha, too. It was bloody heart-breaking.’

Ken and Sasha would not be returning alone. Corporal Jason Barnes, of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME), had been killed two days before Ken and would be on the same flight. The Paras had been practising the repatriation drill although they were, sadly, used to the format now. Afraid that they would look amateurish beside the Para bearers, Frank spoke to their Sergeant Major and it was agreed that the bearer parties would approach the C17 in line rather than the usual side-by-side.

Selecting the bearers was no easy task. The honour of carrying a fallen colleague has its mix of practical (for height) and emotional (who could hold it together long enough). Everyone volunteered for the job but only six could be selected – amongst them was Sasha’s previous handler, Andy Dodds, and, to steady the coffin at the rear, Frank Holmes. Army Chaplain Paul Gallucci knew the unit well – and he knew Ken, too. He had served with them all in Northern Ireland and was well aware of the value of the dog soldiers in theatre and the deep bond that exists between the dog unit and the infantry on the ground. To complete the proper send-off, Marianne Hay was chosen to carry Sasha’s ashes onto the plane. It was the last thing she could do for the dog she loved, trained and served alongside.

Camp Bastion: 11pm, Sunday 27 July

Someone from the REME produced a hip flask. It was a welcome start to the proceedings and broke a little ice. Gazing into the darkness it looked like a disappointing turnout at first, despite there being two men making the return home. The cavernous hold of the C17 gaped open, its ramp down ready to accept the two flag-strewn coffins that sat in the back of the waiting field ambulances. As the lights came up to illuminate the runway the beams caught the truth of the scene. Row upon row of uniformed personnel were waiting in silence. It seemed as if the whole of Camp Bastion had turned out.

Certainly Frank’s wish to get as many dog soldiers there as possible had been granted and the Engineers at the Joint Forces EOD (Explosives Ordnance Disposal) had performed miracles. They had worked with Ken and Sasha and were used to the job split: the dog soldiers locate the explosives and the bomb squad blow them up. It was a good relationship and they felt the loss as keenly as Frank and the rest of his team. Using all their powers and man-management skills, the EOD had successfully brought in all but three of their teams from the various FOBs to attend the ceremony. These were the faces, many tear-stained, shining out of the darkness.

The bearers took the strain of the weight of the coffin first in their hands and then on their shoulders. The practice weight was lighter than this but the responsibility was heavier. Frank Holmes took the rear position, ready to instruct and push up as the party took the slow and careful incline up the ramp and into the body of the plane. Sasha’s former handler, Sergeant Andy Dodds, took front left position: ‘The concentration was immense. The plane is meant to take cargo so the ramp is designed to be smooth underfoot and as I looked ahead to prepare for my first step up I couldn’t help noticing the number of people present and the dogs, too. As I took that first step onto the ramp I became very aware of my legs and feet. I only wanted them to do what my head was telling them. I’m sure all of us were feeling the same. Marianne was walking alone behind us, her arms around the shell casing containing Sasha’s ashes. I’ve no doubt she was trying her very best to hold back tears right to the point where she placed the casing at the head of the coffin.

When Marianne Hay accepted the honour of carrying Sasha’s ashes onto the plane at Camp Bastion she did it to ensure that the dog she trained was repatriated in the way of a hero, to sit at the feet of another hero, her friend and fellow search dog handler, Lance Corporal Kenneth Rowe. With tears welling in her eyes for the loss of the dog she considered closest to her heart and the man she considered to be one of the most talented handlers in the team, Marianne held the brass casing close to her body. As she walked through the soft sound of stifled sobbing, passing colleagues lining the route, she managed to keep her head.

Step by slow step she followed the bearer party up the steep ramp and into the darkness of the body of the plane. It was hard. Hard to do and hard to let go. After setting down the coffin the party paused a moment and hugged each other.

Sergeant Dodds added: ‘Getting through the formalities just as we planned and setting Ken down on the plane was the easier bit. It was saying our personal last goodbyes, the prayers and the group hug that gave most of us the licence to let go of our feelings. The darkness robbed us of a view of the giant C17 lurching into the sky above Bastion but we could hear it loud and clear and knew that it would dip its wings for the final farewell – that was the hardest part. Then, for Ken and for all of us, we had to get the teams back on the ground and take the fight right back to the Taliban.’

Chapter 3

For Queen and country – The Troubles (#ubdef78f9-0bfc-5bed-8f40-1d46f2e631d4)

Ken’s death in July 2008 had highlighted the growing need and respect for the dog soldiers within the wider Army. The demand for search dogs in Afghanistan had massively increased. The patrols appreciated the reassurance of having a search dog with them making safe their route ahead, so the pressure weighed heavy on the RAVC and specifically the men and women of 104 MWD unit to supply the demand. As a Combined Forces operation the pressure radiated out to the Danish and the Americans to provide additional search dog cover too. But the Brit dogs, from the Army and the RAF, were working hard to rise to the challenge. Trouble was, they couldn’t get enough of them on the ground.

Ken Rowe had volunteered to stay on and pick up his R and R later because his replacement had fallen ill and would be out later than expected to support 2 Para. He had been working closely with the unit and was well embedded with them at FOB Inkerman, which was a small but highly volatile spot. Ken was their dog soldier and Sasha was their dog. They already knew that Ken was thorough, trustworthy and a cheeky Geordie and they knew Sasha was a lean, keen and effective search dog. Their relationship had been forged while they lived in sun- and rain-blasted holes in the sand and waited and waited for the attention of the enemy that they knew would show itself – they just didn’t know when. Sasha’s ability to locate deadly devices and hidden weapons and arms had been a literal lifesaver. There was no way Ken was going to leave the men vulnerable. He was staying – and so was Sasha.

Operation Herrick 8 was proving the toughest yet. Death and serious injury were daily occurrences and the regular procession of hearses carrying flag-draped coffins through Wootton Bassett was educating the public in the extent of the sacrifice. The media coverage was also responsible for delivering the emotions attached to the loss into everyone’s home in a very visual way. Even for families untouched by a death or disfigurement, the impression of what was actually happening in Afghanistan was real and almost tangible.

For many of the senior members of the RAVC dog unit this was a reminder of the past and, at some level, the continuing threat in Northern Ireland. Many of the Commanding Officers in Afghanistan had served during The Troubles and others, like Ken Rowe, had later cut their teeth in the Province.

The Army Dog Unit, Northern Ireland, was formed on 1 May 1973. From its base in Ballykelly, County Londonderry, the unit provided critical support to the British Army who first posted troops to the Province in 1969. Only expecting to be needed for a few weeks to support the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the Army quickly realised that it would take more than short-term peacekeeping activity to quell the violent and ongoing clashes that had broken out between the Protestants and Catholics. By July 1973 the Army Dog Unit found itself at the heart of The Troubles when it lost the first of four of its number to terrorist activities.

Corporal Bryan Criddle, BEM, was the first of their fallen. He was patrolling the border at Clogher in County Tyrone with C Squadron, The Royal Tank Regiment, when his search dog, Jason, indicated (pointed out explosives) on a milk churn, one of several set out in a horseshoe formation. Bryan was working in recognised ‘bandit country’: if his dog was telling him explosives were present – they were. What he could not know was that the terrorists were watching. The milk-churn bomb was detonated remotely, leaving Bryan with life-threatening head injuries. He was helicoptered out to Musgrave Park hospital but lost his battle for life four days later. Jason was blown 30 feet in the air but by some miracle survived. Colleagues reported that the dog went into protective mode the second Bryan went down and had to be pulled off his master as he wouldn’t let anyone get close to help. Jason was airlifted, too, and after a veterinary checkover was transferred to the kennels at the Maze Prison to recuperate.

Corporal Criddle was killed just weeks after being awarded the British Empire Medal (BEM) for his service with the Army Dog Unit in Northern Ireland; in July Jason had been awarded his ‘wings’ for completing 1,000 flying hours in helicopters operating between the garrison and the border to carry out his duties. This was recognition for the soldier and the dog, but it also drew attention to the unique role of the entire unit.

At that time the Army Dog Unit was a relatively small part of the RAVC, but its special skills were making a difference in Northern Ireland where the terrorist threat was often not just hidden from human eyes but it shifted in shape and composition all the time. In addition to the RAVC, dog handlers were recruited from volunteer dog soldiers within all regiments and corps of the Army and the dogs were trained in three disciplines: guard/attack dogs (known as Snappers or Land Sharks), tracker dogs (known as Groundhogs), and vehicle search dogs and arms and explosives search dogs – the Wagtails. The dogs and the soldiers were lifesavers no matter which of three disciplines they excelled in, but they were also targets.

In 1974 the then Commander Land Forces Northern Ireland, Major General Peter Leng, MC MBE, granted the ADU NI RAVC the right to wear a Red Paw badge in their berets to the left of their regimental cap badge. The enamel badge, measuring a quarter of an inch, was to unite the members of this specialist unit. The Red Paw badge represented the bloody paws of the dogs who carried out their duties, often walking on broken glass and in the shadow of death. The dog soldiers wore it with pride.

On the Bank Holiday weekend, 25 May 1991, Corporal Terry ‘Geordie’ O’Neill and his colleague Corporal Darren Swift, ‘Swifty’, were with their dogs, Blue and Troy, in the exercise yard at the Army barracks at North Howard Street Mill when a terrorist hurled a ‘coffee-jar’ bomb (containing Semtex, a detonator and ‘shipyard confetti’ – nuts, bolts, nails, rivets, etc) from the fire escape of the snooker hall next door. The homemade bomb landed at the soldiers’ feet, killing Geordie instantly and taking Darren Swift’s legs – and a finger – clean away. Blue and Troy miraculously survived the blast but needed veterinary care for their burnt paws. One life was taken and the other changed forever in one brief, brutal and deliberate act of violence.

Terry O’Neill was the last dog soldier to die in Northern Ireland but in the campaign that became known as Operation Banner (1969–2007) 763 military personnel lost their lives. After a deployment that spanned 38 years, the British Army left the Province. The dog handlers felt a definite wind-down as Op Banner drew to an end and their relocation as 104 MWD to North Luffenham became a reality.

At midnight on 31 July 2007 the Army Dog Unit Northern Ireland ceased to exist. The closing parade at Ballykelly marked the end of an era; a bitter-sweet period of living in a community riddled with fear while enjoying unrivalled camaraderie. It was where the Red Paw badge became a mark of distinction and symbol of courage. Young soldier Ken Rowe wore his with pride.

By 10 August 2007 North Luffenham was home to 104 Military Working Dog Support Unit and Ken was part of the ‘lumping and dumping’ of equipment at the St George’s Barracks. For the next five months he played a key role in establishing the new unit out of everything that had made its way out of Northern Ireland and, at the same time, continuing to improve his skills and knowledge as a dog handler. Northern Ireland had been his first posting and it had given Ken a platform to showcase his skills and get himself known. He quickly gained a reputation for having a thirst for knowledge and a desire to progress his dog, himself and his career. He was also known for his level of fitness and skill as a footballer.

Encouraging everyone in the unit to take part in a four-mile run, three or four times a week – with the dogs – was not everyone’s idea of fun, but to Ken Rowe is was a great way to beat the boredom of the wind-down. According to Frank Holmes, who assessed Ken out there as part of the veterinary services training evaluation team, he was ‘… quite simply a dream to manage. He was fit and friendly, except when he had a beer. Then he was a pain! He was keen to work and volunteer and, most importantly, he always had a smile on his face.’

When it came to dogs Ken Rowe was in his element. His Northern Ireland tour gave him the chance to handle a series of Protection Dogs, known in the Army as Land Sharks – all hair, teeth and attitude on the end of a leash. German Shepherd Max and Black Labradors Odie and Jackdaw proved challenging, but that’s what Ken loved the most. He had a way with dogs that others couldn’t handle, and that’s one of the reasons why he stood out from the crowd. There were always the dogs that didn’t live up to their potential because, like people, they are individuals who may have all the credentials on paper but lack the ability to apply those skills in practice. Ken could sort the wheat from the chaff and knew when a dog didn’t have what it took to work well in that environment. It was Odie that Ken took to the most, so much so, in fact, that he brought him back to Newcastle. The dog was looking for a good home for retirement so Ken came up with a failsafe plan to give this dog a richly deserved, peaceful home for the rest of his life. Odie went to live on a farm in Bedlington, far away from his life in the Army.

It was while Ken was in Northern Ireland that he had his first encounter with losing a colleague; worse still, it was Ken who discovered the body. It was Christmas at RAF Aldergrove and while the other protection dog handlers were making the best of a bad lot away from home, one young soldier, Lance Corporal John Murphy, decided that, for some reason, enough was enough. Ken was concerned because when he had last seen John he thought he looked very down and preoccupied. Christmas was not a time to be anything but happy and in party mood; that’s what Ken was used to. It was probably the thought of someone not enjoying themselves that drove Ken to find his friend and cheer him up.

What he found when he reached John’s quarters was to stay with Ken in his waking and sleeping hours. He found his friend had taken his own life, and despite Ken’s desperate attempts to revive him it was too late. Finding a friend and colleague, a young man like himself but with a family, was hard on Ken and he looked to the more experienced members of the unit for advice. Frank Holmes was well placed to keep a close eye on him and to make sure the cheeky Geordie in Ken Rowe was never too far away. One thing Frank knew for sure was that Ken’s family would support him through the trauma and get him back on track for what lay ahead.