По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

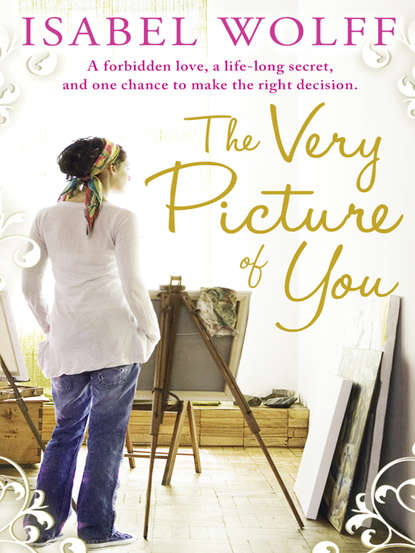

The Very Picture of You

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Iris sat on the sofa, smoothed down her skirt then turned towards me. As I looked at her, I felt the frisson I always feel when I begin a new portrait. We were silent for a while, the brush scraping softly across the canvas as I began to block in the main shapes with an ochre wash.

After a couple of minutes Iris shifted her position.

‘Are you comfortable?’ I asked her, concerned.

‘I am – though I confess I feel a little self-conscious.’

‘That’s normal,’ I assured her. ‘A portrait sitting’s quite a strange experience – for both parties – because there’s this sudden relationship. I mean, we’ve only just met, but here I am, openly gawping at you: it’s a pretty unnatural first encounter.’

Iris smiled. ‘I’m sure I’ll soon get used to your… scrutiny. But wouldn’t you rather be painting someone young?’

‘No. I prefer painting older people. It’s much more interesting. I love seeing a whole life etched on to a face, with all that experience, and insight.’

‘And regret?’ Iris suggested quietly.

‘Yes… that’s usually there too. It would be strange if it wasn’t.’

‘So… do your sitters ever get upset?’

My brush stopped. ‘They do – especially the older ones, because as they sit there they’re looking back on their lives. Sometimes people cry.’ I thought of Mike and wondered again what could have happened to make him so unhappy.

‘Well, I promise not to cry,’ Iris said.

I shrugged. ‘It doesn’t matter if you do. I’m going to paint you, Iris, in all your humanity, as you are – or as I see you, at least.’

‘You have to be perceptive then, to do what you do.’

‘That’s true.’ I exhaled. ‘And I couldn’t even try to do this if I didn’t believe that I was. Portrait painters need to be able to detect things about the sitter – to try to work out who that person is.’

We continued in silence for a few moments.

‘And do you ever paint yourself?’

My brush stopped in mid-stroke. ‘No.’

Surprise flickered across Iris’s features. ‘I thought portrait artists usually did do self-portraits.’

You’re Ella Graham now…

‘Well… I don’t – at least not for years now.’

And that’s all there is to it…

‘But… I’d love to hear more about your time abroad, Iris. You must have met some remarkable people.’

‘I did,’ she said warmly. ‘Well, they weren’t just people, they were personalities. Let me see… Whose names can I drop?’ She narrowed her eyes. ‘We met Tito,’ she began. ‘And Indira Gandhi – I have a photo of Sophia, aged five, sitting on her lap. I also met Nasser – the year before Suez; I danced with him at an embassy ball. In Chile we met Salvador Allende: Ralph and I liked him enormously and were outraged at what the Americans did to help overthrow him, though we could never say so openly. Discretion is a frustrating, if necessary, aspect of diplomatic life.’

‘What was your favourite posting?’

Iris smiled. ‘Iran. We were there in the mid-1970s – it was paradisally beautiful and I have wonderful memories of our time there.’

‘But presumably your daughters went to boarding school?’

She nodded. ‘In Dorset. They weren’t able to join us for every holiday, so that was hard. Their guardian was very good, but we hated being separated from our two girls.’

There was another silence, broken only by the dull rumble of traffic in Kensington Church Street.

‘Iris… I hope you don’t mind my asking you – but the painting in your bedroom…’

She shifted slightly. ‘Yes?’

‘You said it made you feel sad. I can’t help wondering why – as it’s such a happy scene.’

Iris didn’t at first reply, and for a few moments I wondered whether she wasn’t, in fact, slightly deaf; and I was considering whether to ask her again when she exhaled, painfully. ‘That picture makes me feel sad because there is a sad story attached to it – one I learned a few years after I’d bought it.’ She heaved another deep sigh. ‘Perhaps I’ll tell you…’

I felt crass suddenly. ‘You don’t have to, Iris – I didn’t mean to pry: I was just surprised by your remark, that’s all.’

‘That’s perfectly understandable. It is, on the surface, a happy scene. Two little girls playing in a park…’ She paused, then looked at me intently. ‘I will tell you the story, Ella – because you’re an artist and I believe you’ll understand.’ Understand what, I wondered. What could the sad story behind the painting be? It now occurred to me, with an anxious pang, that the girls might not have survived the war – or perhaps something awful had happened to the nanny. Now I wasn’t sure that I wanted to hear the story, but Iris was beginning.

‘I bought the painting in May 1960,’ she said. ‘We were in Yugoslavia then – our first posting; but I’d come home with Sophia, who was then three, to have my second child, Mary. There were good hospitals in Belgrade, but I decided to have the baby in London so that my mother could help me. Also, she was widowed by then and I wanted to take the opportunity to spend some time with her; so I went to stay with her for three months.’

I studied Iris, and drew in the curve of her right cheek.

‘My mother’s house was in Bayswater. She’d spent most of her married life in Mayfair but, as I say, my stepfather lost everything after the war.’ I wondered about Iris’s own father. ‘The week before the baby was due I took Sophia out in her pushchair. We had an ice cream in Whiteleys then walked slowly up Westbourne Grove: and I was just passing a small antique shop when I glanced in the window and saw that painting. I remember stopping dead and staring at it: I was completely taken with it – as you have been today. Sophia turned round and squawked at me to go on, so I did. But I couldn’t get the picture out of my mind. So, a few minutes later I turned back and pushed on the door.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: