По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

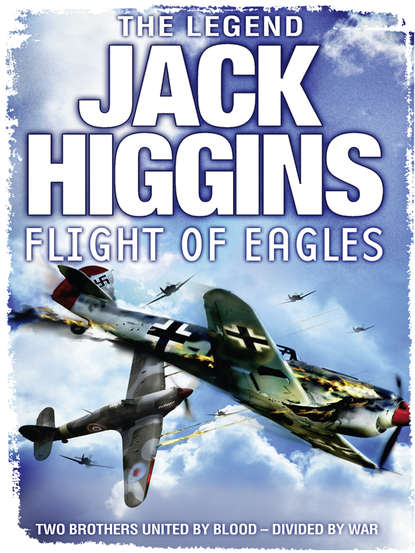

Flight of Eagles

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well, my father knocked down at least forty-eight of ours with the Flying Corps. I think I can manage.’

Galland laughed out loud and stuck a small cigar between his teeth. ‘I’ll follow you up. Let’s see.’

The display that followed had even Goering breathless. Galland could not shake Max for a moment, and it was the Immelmann turn which finished him off. He turned in to land, and Max followed.

Standing beside the Mercedes, Goering nodded to a valet, who provided caviar and champagne. ‘Took me back to my youth, Baroness, the boy is a genius.’

This wasn’t false modesty, for Goering was a great pilot in his own right, and had no need to make excuses to anybody.

Galland and Max approached, Galland obviously tremendously excited. ‘Fantastic. Where did you learn all that, boy?’

Max told him and Galland could only shake his head.

That night, he joined Goering, von Ribbentrop, Elsa and Max at dinner at the Adlon Hotel. The champagne flowed. Goering said to Galland, ‘So what do we do with this one?’

‘He isn’t seventeen until next year,’ Galland said. ‘May I make a suggestion?’

‘Of course.’

‘Put him in an infantry cadet school here in Berlin, just to make it official. Arrange for him to fly at the Aero Club. Next year, at seventeen, grant him a lieutenant’s commission in the Luftwaffe.’

‘I like that.’ Goering nodded and turned to Max. ‘And do you, Baron?’

‘My pleasure,’ Max Kelso said, in English, his American half rising to the surface easily.

‘There is no problem with the fact that my son had an American father?’ Elsa asked.

‘None at all. Haven’t you seen the Führer’s new ruling?’ Goering said. ‘The Baron can’t be anything else but a citizen of the Third Reich.’

‘There’s only one problem,’ Galland put in.

‘And what’s that?’ Goering asked.

‘I insist that he be kind enough to teach me a few tricks, especially that Immelmann turn.’

‘Well, I could teach you that,’ Goering told him. ‘But I’m sure the Baron wouldn’t mind.’ He turned. ‘Max?’ addressing him that way for the first time.

Max Kelso said, ‘A pity my twin brother, Harry, isn’t here, Lieutenant Galland. We’d give you hell.’

‘No,’ Galland said. ‘Information is experience. You are special, Baron, believe me. And please call me Dolfo.’

It was to be the beginning of a unique friendship.

In America, Harry went to Groton for a while, and had problems with the discipline, for flying was his obsession and he refused to sacrifice his weekends in the air. Abe Kelso’s influence helped, of course, so Harry survived school and went to Harvard at the same time his brother was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Luftwaffe.

The Third Reich continued its remorseless rise and the entire balance of power in Europe changed. No one in Britain wanted conflict, the incredible casualties of the Great War were too close to home. Harry ground through university, Europe ground onwards into Fascism, the world stood by.

And then came the Spanish Civil War and they all went, Galland and Max, taking HE51 biplanes over the front, Max flying 280 combat missions. He returned home in 1938 with the Iron Cross Second Class and was promoted to Oberleutnant.

For some time he worked on the staff in Berlin, and was much sought after on the social circuit in Berlin, where he was frequently seen as his mother’s escort, and was a favourite of Goering, now become all-powerful. And then came Poland.

During the twenty-seven-day Blitzkrieg that destroyed that country, Max Kelso consolidated his legend, shot down twenty planes, received the Iron Cross First Class and was promoted to captain. During the phoney war with Britain and France that followed, he found himself once again on the staff in Berlin.

In those euphoric days, with Europe in its grasp, everything seemed possible to Germany. Max’s mother was at the very peak of society and Max had his own image. No white dress jackets, nothing fancy. He would always appear in combat dress: baggy pants, flying blouse, a side cap, called a Schiff, and all those medals. Goebbels, the tiny, crippled Nazi propaganda minister, loved it. Max appeared at top functions with Goering, even with Hitler and his glamorous mother. They christened him the Black Baron. There was the occasional woman in his life, no more than that. He seemed to stand apart, with that saturnine face and the pale straw hair, and he didn’t take sides, was no Nazi. He was a fighter pilot, that was it.

As for Harry, just finishing at Harvard, life was a bore. Abe had tried to steer him towards interesting relationships with the daughters of the right families, but, like his brother, he seemed to stand apart. The war in Europe had started in September. It was November 1939 when Harry went into the drawing room and found Abe sitting by the fire with a couple of magazines.

‘Get yourself a drink,’ Abe said. ‘You’re going to need it.’

Harry, at that time twenty-one, poured a Scotch and water and joined his grandfather. ‘What’s the fuss?’

Abe passed him the first magazine, a close-up of a dark taciturn face under a Luftwaffe Schiff, then the other, a copy of Signal, the German forces magazine. ‘The Black Baron,’ Abe said.

Max stood beside an ME 109 in flying gear, a cigarette in one hand, talking to a Luftwaffe mechanic in black overalls.

‘Medals already,’ Harry said. ‘Isn’t that great? Just like Dad.’

‘That’s Spain and Poland,’ Abe said. ‘Jesus, Harry, thank God they call him Baron von Halder instead of Max Kelso. Can you imagine how this would look on the front page of Life magazine? My grandson the Nazi?’

‘He’s no Nazi,’ Harry said. ‘He’s a pilot. He’s there and we’re here.’ He put the magazine down. Abe wondered what he was thinking, but as usual, Harry kept his thoughts to himself – though there was something going on behind those eyes, Abe could tell that. ‘We haven’t heard from Mutti lately,’ Harry said.

‘And we won’t. I speak to people in the State Department all the time. The Third Reich is closed up tight.’

‘I expect it would be. You want another drink?’

‘Sure, why not?’ Abe reached for a cigar. ‘What a goddamn mess, Harry. They’ll run all over France and Britain. What’s the solution?’

‘Oh, there always is one,’ Harry Kelso said and poured the whisky.

Abe said, ‘Harry, it’s time we talked seriously. You graduated magna cum laude last spring, and since then all you do is fly and race cars, just like your father. What are you going to do? What about law school?’

Harry smiled and shook his head. ‘Law school? Did you hear Russia invaded Finland this morning?’ He took a long drink. ‘The Finns need pilots badly, and they’re asking for foreign volunteers. I’ve already booked a flight to Sweden.’

Abe was horrified. ‘But you can’t. Dammit, Harry, it’s not your war.’

‘It is now,’ Harry Kelso told him and finished his whisky.

The war between the Finns and the Russians was hopeless from the start. The weather was atrocious and the entire country snowbound. The Army, particularly the ski troops, fought valiantly against overwhelming enemy forces but were pushed back relentlessly.

On both sides, the fighters were outdated. The most modern planes the Russians could come up with were a few FW190s Hitler had presented to Stalin as a gesture of friendship between Germany and Russia.

Harry Kelso soon made a name for himself flying the British Gloucester Gladiator, a biplane with open cockpit just like in the First World War. A poor match for what he was up against, but his superior flying skills always brought him through and as always, just like his father in the First World War, Tarquin sat in the bottom of the cockpit in a waterproof zip bag Harry had purchased in Stockholm.

His luck changed dramatically when the Finnish Air Force managed to get hold of half a dozen Hurricane fighters from Britain, a considerable coup in view of the demand for the aircraft by the Royal Air Force. Already an ace, Harry was assigned to one of the two Hurricanes his squadron was given. A week later, they received a couple of ME109s from a Swedish source.

He alternated between the two types of aircraft, flying in atrocious conditions of snowstorms and high winds, was promoted to captain and decorated, his score mounting rapidly.

A photo journalist for Life magazine turned up to cover the air war, and was astonished to discover Senator Abe Kelso’s grandson and hear of his exploits. This was news indeed, for Abe was now very much a coming man, a member of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s kitchen cabinet.