По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

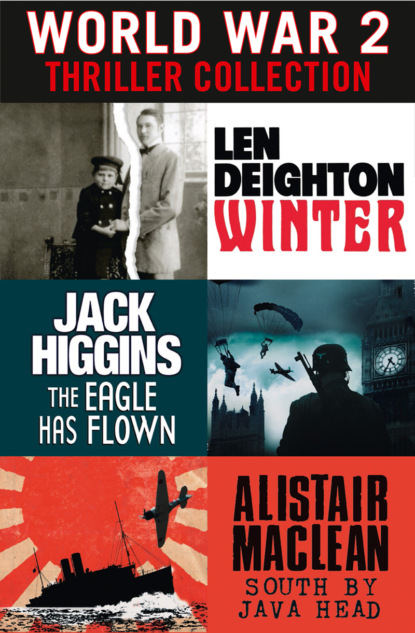

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The man behind the desk still said nothing. Glenn Rensselaer looked round the gloomy little upstairs room on Washington’s K Street. Ancient floral wallpaper, an old desk, some dented filing cabinets, a worn carpet, and in the corner a large brass spitoon, brightly polished. So this was the U.S. State Department’s idea of a suitable office for its ‘research and intelligence subsection’. Was it secrecy, parsimony, or neglect?

‘On the other hand,’ said Glenn Rensselaer, more to break the silence than because he felt the man behind the desk was interested, ‘for a lot of people Germany right now is where everything is happening. The movies, legitimate theatre, the opera, popular music, light opera, orchestral music, science – from atomic physics to psychology – architecture, industrial design, painting … every damn thing.’ He stubbed out his cigarette and added, ‘Is all this boring you? I have the feeling that there are other things you’d rather be doing.’

‘Not at all,’ said the bald young official. ‘I find everything you tell me fascinating. But I’m likely to be the only person in the whole State Department who will read your report all through.’

‘Is that so?’

‘The U.S. has lost interest in Europe, except to count how many battleships the British are building under the terms of the new treaty.’

‘You’re talking in riddles.’

‘Forgive me: I don’t mean to. What I should have said is that right now no one wants to talk about anything but Japanese naval strength. You must be familiar with the terms of the 1922 conference – a ratio of five British capital ships and three Japanese capital ships for five of ours. You don’t have to be a mathematician to see that under the terms of that treaty the combined naval strength of the Japs and the Brits would gun us off both oceans.’

‘You don’t have to be a mathematician,’ agreed Glenn Rensselaer. ‘You just have to be nuts.’

Again came the inscrutable look. No reply. Perhaps Glenn should not have come here wearing his old jacket and flannels with his brightly patterned bow tie and knitted pullover. The man behind the desk was in a tight-fitting suit with a stiff collar. Glen had forgotten what it was like in Washington, D.C.

Glenn persisted. ‘You’re not seriously suggesting that we’re likely to get into a fight against the British, are you?’

‘It’s our job to take into account even the most unlikely eventuality, Mr Rensselaer.’

‘You guys are out of your minds. If we tangled with the Japs, the British would be alongside us.’ He got to his feet and the man got up, too.

‘I’m sure you’re right, Mr Rensselaer,’ said the man in a voice that betrayed nothing of his thoughts. ‘Anyway, it was good of you to come. We don’t get much first-hand news these days.’

Glenn Rensselaer was glad to get back to his parents’ house in New York. It was home to him, for his travels abroad made it convenient and convivial for his wife to share his father’s large mansion. She got along well with Cy Rensselaer’s second wife, Dot, and now that Dot’s three sons had grown up and left home, she was company for the older woman.

When he returned from his trip to Washington, his father asked him about it, but Glenn was unforthcoming. Had he explained his reception at the bureaucrats’ ‘secret’ office, his father would probably have taken exception to the description. The Republican Party firmly controlled House and Senate. Calvin Coolidge was in the White House. The old man preferred to believe that the men in Washington knew what they were doing. It was a point of view difficult to sustain after a trip to the capital, which was perhaps why his father never went there.

So Glenn talked to his father about Germany. ‘Since the war you see on the streets this large rootless proletariat,’ Glenn told his father. ‘Mostly from the East: Poles, Czechs, Russians, Hungarians, Rumanians, gypsies, dispossessed smallholders and peasants, factory workers, and God knows who. In order to blame these badly dressed, incoherent outsiders for every misfortune from petty crime to factory closures and job losses, a name was required. So the Germans have decided to call them “Jews”.’

‘Don’t make jokes about Jews, son. I can’t abide it, never could.’

‘I’m not joking. Anti-Semitism is everywhere; you smell it in the air.’

‘That’s not just in Europe, Glenn.’

‘No, but in France and England and here in the U.S. anti-Semitism is a form of envy. It’s mostly directed at the rich, clever and successful. The anti-Semite depicts the Jew as a man with a diamond tie pin, in a big automobile, smoking a cigar, and coming to collect the profits from his factory. In Germany they have that anti-Semitic envy, too. And it’s especially strong there because the Jew plays a vital part in the cultural life of Germany. The movies, the theatre, publishing and the art world are conspicuously dominated by Jews. But there’s this other sort of anti-Semitism, too.’

‘Does it really matter?’

His father felt uncomfortable, but Glenn continued: ‘It’s a downward-looking anti-Semitism. I’m talking about the fear of any strange-looking, penniless itinerant. Now, add that to the envy and you’ve got an explosive mixture. That’s why Germany is unique. This double anti-Semitism comes from Germany’s geographical position; that’s why it’s different from anything you find in other countries. And let me tell you that there are a hell of a lot of German politicians who know exactly how to stir up that mixture.’

‘Is it the Nazis you’re talking about? Only last week there were pictures in one of the weeklies.’

‘There are others, but the Nazis are the most dedicated and the most dangerous. This fellow Hitler has renewed strength since being in prison. Politically it’s the best thing that could have happened to him. He’s a sort of romantic, and he understands that blend of sentimentality and cruelty that is uniquely German. He knows how to appeal to a lot of different Bavarian malcontents. Want to restore the monarchy? Hitler’s your man. Feel the nice Bavarian Catholics are ill-treated by nasty Prussian Protestants? Hitler. Want to hear that the bureaucrats in Berlin are the cause of Bavaria’s troubles? Want to hear that the General Staff – Protestant every one – lost the war? Lost your job? A Jew took it from you. Your factory went out of business? A Jewish boss did it and made a profit on the deal. Socialists organizing a strike you don’t like? Communists fighting in the street? Everyone knows Moscow is run by Jews. You don’t agree? Then either you are being duped or you are a Jew and a part of the conspiracy.’

‘That might sound good to voters in Bavaria, but it won’t get Mister Hitler very far if he wants to get into the national government. The way I hear it, Hitler is virtually unknown outside of Bavaria, and my guess is he’ll stay that way.’

‘You don’t know this guy. Don’t imagine he has any kind of written manifesto that you can challenge him on. He’s all things to all men. He trades on emotions, not facts. When he goes for the Reichstag he’ll have a fresh set of answers ready. This guy is dynamite. We had an office in Munich. I’ve heard him speaking at his meetings. He holds people spellbound. He’s full of spite, brimful of hatred and contempt. There is nothing constructive in what he says: just threats of what he’ll do to the sort of people he blames for all the troubles.’

‘All politicians are negative,’ said his father. ‘A promise to punish the fortunate and soak the rich is always good for a few votes.’

‘But in Germany too many people are ready to believe in the quick and easy solution.’

‘It will all pass,’ said his father. There was a note of weariness detectable in his voice. His father was still so energetic that it was difficult to believe he was seventy-four years old, except when now and again the mask slipped. ‘It’s the legacy of war – defeat, disappointment, hunger. It will pass.’

‘I wish I could believe you, Dad. But the fact is that this poison is more prevalent among students than among any other sector of the population. Students – university students for the most part – fellows who were too young to go to the war, are more bitter about the defeat than the soldiers who were in the fighting. Veterans know in their hearts that the Germans were licked on the battlefield; the kids who weren’t there like to believe all that “stab-in-the-back” stuff. And the kids are the ones who get violent. They are full of energy and full of hate. They are looking for a cause, and Hitler will provide it for them.’

‘For God’s sake, don’t tell the Danzigers any of this, Glenn. Lottie’s father is worried sick at the idea of her remaining in Berlin. He always calls me up when he comes into town, and we usually lunch at the club. Some idiot friend of his sent him clippings from German newspapers. He had his office translate the stuff. I don’t know what it said, but he’s darned worried. So don’t tell him, huh?’

‘The club? Is Mr Danziger now a member of the club?’

His father looked flustered. ‘Well, no. They still have that stupid rule about members … but taking a Jew in as a guest is okay.’

Glenn could think of nothing to say. They sat in silence for a few moments. Outside there was the continual sound of motorcars, it was hard to believe that when he was a child the house had been so quiet.

‘He’s letting some little film company build movie lots and stages on his orange groves.’

‘Danziger?’ said Glenn.

‘Just a handful of cash and twenty-five per cent of the movie company.’

‘Is it a good deal?’

‘He’s gone soft in the head, if you ask me. Twenty-five per cent of nothing is nothing. Just like ninety-nine per cent of nothing is nothing. And what’s a movie company got in assets except its real estate?’

‘Did you tell Danziger that?’

‘Contracts, he says. Contracts with actors. Can you imagine how that would show on the auditors’ books?’

‘Movies are doing okay, aren’t they?’

‘Do you know how long it will take him to get real quality fruit growing there again?’

‘Danziger can afford a few mistakes,’ said Glenn Rensselaer.

‘I’m not sure he can,’ said his father. ‘The Danzigers are not rich.’

Glenn smiled.

‘I’m serious.’

‘I know you are, Dad, but I remember you telling me that his assets would total some five million dollars. How can you say he’s not rich?’

The old man did not reply for a moment. He didn’t think it was funny. But Glenn Rensselaer had noticed that this obsession with money, the raw measure of power that money represented, was one of the few ways in which his father’s old age showed. ‘To tell you frankly, I wasn’t happy to think of his eldest daughter marrying into the family. Lottie is a nice enough girl, of course, but not right for little Peter.’

‘Your “little Peter” is now a qualified lawyer and a junior partner in Winter’s holding company.’