По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

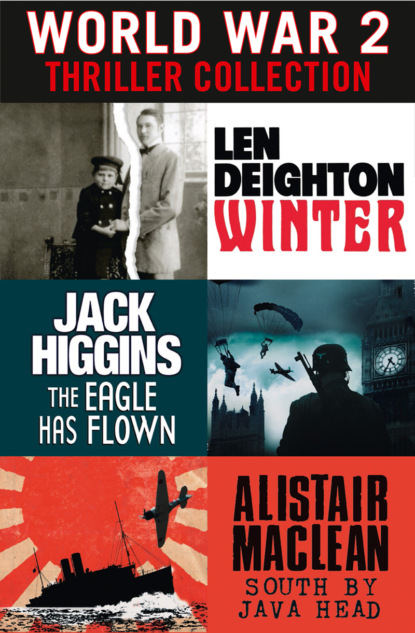

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘If Kupka prevents you from leaving Austria…’ For a moment Winter was puzzled. Then he realized what the proposal really was. ‘Do you mean that you came here hoping that I would refuse to do as Kupka demands but not tell him so until you were across the border?’

‘You’re a German.’

‘So you keep reminding me,’ said Winter. He gulped the rest of his brandy. ‘But I have business interests here, and a house. How can you expect me to defy the authorities for a stranger?’

‘For a client,’ said Petzval. ‘I’m not a stranger; I’m a client of the bank.’

‘But you ask too much,’ said Winter. He got up, reached for his hat, and tossed some coins onto the table. It was more than enough to pay for his coffee and the brandy, as well as any coffees and brandies that Petzval might have consumed while waiting for him. ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Herr Petzval.’ As Winter walked down the café he heard some sort of commotion, but he didn’t turn until he heard Petzval shouting.

Petzval was standing and shaking his fist. Then he grabbed the coins and with all his might threw them at Winter. At least two of the coins hit the glass of the revolving doors. Winter flinched. There was a demon in this fellow Petzval. Two waiters grabbed him, but still he struggled to free himself, so that a third waiter had to clamp his arms round Petzval’s neck.

‘Damn you, Winter! And damn your money! I curse you, do you hear me?’

Winter was trembling as he pushed his way through the revolving doors and out into the darkness of Gumpendorfer Strasse. Of course the fellow was quite mad, but his curses were still ringing in Winter’s head as he climbed into his horseless carriage. He couldn’t help thinking it was a bad omen: especially with his second child about to be born at almost any moment.

Winter woke up and wondered where he was for a moment before remembering that he was in his Vienna residence. It seemed so different without his wife. Usually a good night’s sleep was all that Harald Winter needed to recuperate from the stresses and anxieties of his business. But next morning, sitting in his dressing room with a hot towel wrapped across his face, he had still not forgotten his encounter with the violent young man.

Winter removed the hot towel and tossed it onto the marble washstand. ‘Will there be a war, Hauser?’ Winter asked while his valet poured hot water from the big floral-patterned jug and made a lather in the shaving cup.

The valet lathered Winter’s chin. He was an intelligent young man from a village near Rostock. He treasured his job as Winter’s valet; he was the only member of Winter’s domestic household who unfailingly travelled with his master. ‘Between these Austrians and the Serbs, sir? Yes, people say it’s sure to come.’ The razors, combs and scissors were sterilized, polished bright, and laid out precisely on a starched white cloth. Everything was always arranged in this same pattern.

‘Soon, Hauser?’

The valet stopped the razor. He was too bright to imagine that his master was consulting him about the likelihood of war. Such predictions were better left to the generals and the politicians, the sort of men whom Winter rubbed shoulders with every day. Hauser was being asked what people said in the streets. The sort of people who lived in the huge tenement blocks near the factories; workers who lived ten to a room, with all of them paying a quarter of their wages to the landlords. Men who worked twelve-and even fourteen-hour days, with only Sunday afternoons for themselves. What were these men saying? What were they saying in Berlin, in Vienna, Budapest and London? Winter always wanted to know such things and Hauser made it his job to have answers. ‘These Austrians like no one, sir. They are jealous of us Germans, hate the Czechs and despise the Hungarians. But the Serbs are the ones they want to fight. Sooner or later everyone says they’ll finish them off. And Serbia is not much; even the Austrians should be able to beat them.’ He spoke of them all with condescension, as a German has always spoken of the Balkan people and the Austrians, who seemed little different.

Winter smiled to himself. Hauser had all the pride – arrogance was perhaps the better word – of the Prussian. That’s why he liked him. Hauser steadied his master’s chin with finger and thumb as he drew the sharpened razor through the lather and left pink, shiny skin. As Hauser wiped the long razor on a cloth draped over his arm, Winter said, ‘The terrorists and the anarchists with their guns and bombs …murdering innocent people here in the streets. They are all from Serbia. Trained and encouraged by the Serbs. Wouldn’t you be angry, Hauser?’

‘But I wouldn’t join the army and march off to war, Herr Winter.’ He lifted Winter’s chin so that he could bring the razor up the throat. ‘There are lots of people I don’t like, but I can see no point in marching off to fight a war about it.’

‘You’re a sensible fellow, Hauser.’

‘Yes, Herr Winter,’ said Hauser, twisting Winter’s head as he continued his task.

‘We are fortunate to live in an age when wars are a thing of the past, Hauser. No need for you to have fears of riding off to war.’

‘I hope not,’ said Hauser, who had no fears about riding off to war: only gentlemen like Herr Winter went off to war on chargers; Hauser’s class marched.

‘Battles, yes,’ said Winter. ‘The Kaiser will have to teach the Chinese a lesson, the English send men into the Sudan or to fight the Boers – but these are just police actions, Hauser. For us Europeans, war is a thing of the past.’

Hauser turned his master’s head a little more and started to trim the sideburns. He cut them a fraction shorter each time. Side whiskers were fast going out of fashion and, like most domestic servants, Hauser was an unrepentant snob about fashions. He always left Winter’s moustache to the end. Trimming the blunt-ended moustache was the most difficult part. He kept another razor solely for that job. ‘So the Austrians won’t fight the Serbs?’ said Hauser as if Winter’s decision would be final.

‘The Balkans are not Europe,’ said Winter, turning to face the wardrobe so that Hauser could trim the other sideburn. ‘Those fellows down in that part of the world are quite mad. They’ll never stop fighting each other. But I’m talking about real Europeans, who have finally learned how to live together, and settle differences by negotiation: Germans, Austrians, Englishmen … even the French have at last reconciled themselves to the fact that Alsace and Lorraine are German. That’s why I say you’ll never ride off to war, Hauser.’

‘No, Herr Winter, I’m sure I won’t.’

There was a light tap at the door. Hauser lifted his razor away in case his master should make a sudden move. ‘Come in,’ said Winter.

It was one of the chambermaids; little more than fourteen years old, she had a Carinthian accent so strong that Winter had her repeat her message three times before he was sure he had it right. It was the senior manager from the Vienna branch of the bank. What could have got into the man, that he should come disturbing Winter at nine-thirty in the morning at his residence? And yet he was usually a sensible and restrained old man. ‘Very urgent,’ said the little chambermaid. Her face was bright red with excitement at such unusual goings-on. She’d seen the master being shaved; that would be something to brag about to the parlourmaid. ‘Very, very urgent.’

‘That’s quite enough, girl,’ said Hauser. ‘Your master understands.’

‘Show him up,’ said Winter.

Hauser coughed. Show him up to see Winter when he was not even shaved? And this was the tricky part: shaving round the master’s moustache. Hauser didn’t want to be doing that with an audience, and there was the chance that Winter would start talking; then anything could happen. Suppose his hand slipped and he made a cut? Then what would happen to his good job?

‘I’m deeply sorry to disturb you, Herr Winter,’ said the senior manager as he was shown into the room. This time the butler was with the visitor, instead of that scatterbrained little chambermaid. Hauser noticed that the butler’s fingers were marked with silver polish. That job should have been completed last night. These damned Austrians, thought Hauser, are all slackers. He wondered if Winter would notice.

‘It’s this business with Petzval,’ said the senior manager. He had big old-fashioned muttonchop whiskers in the style of the Emperor.

Winter nodded and tried not to show any particular concern.

‘I wouldn’t have disturbed you, but the messenger from Count Kupka said you should be told immediately…. I felt I should come myself.’

‘Yes, but what is it?’ said Winter testily.

‘He died by his own hand,’ said the senior manager. ‘The messenger emphasized that there is no question of foul play. He made that point most strongly.’

‘Suicide. Well, I’m damned,’ said Winter. ‘Did he leave a note?’ He held his breath.

‘A note, Herr Direktor?’ said the old man anxiously, wondering if Winter was referring to a promissory note or some other such valuable or negotiable certificate. And then, understanding what Winter meant, he said brightly, ‘Oh, a suicide note. No, Herr Direktor, nothing of that sort.’

Winter tried not to show his relief. ‘You did right,’ he said. He felt sick, and his face was flushed. He knew only too well what could happen when things like this went wrong.

‘Thank you, Herr Direktor. Of course I went immediately to the records to make sure the bank’s funds were not in jeopardy.’

‘And what is the position?’ asked Winter, wiping the last traces of soap from his face while looking in the mirror. He was relieved to notice that he looked as cool and calm as he always contrived when with his employees.

‘It is my understanding, Herr Winter, that, while the death of the debtor irrevocably puts the surety wholly into the possession of the nominated beneficiary, the bank’s obligation ends on the death of the other party.’

‘And how much of the loan has been paid to Petzval so far?’

‘He had a twenty-crown gold piece on signature, Herr Direktor. As is the usual custom at the bank.’

‘So this small tract of land on the Obersalzberg has cost us no more than twenty crowns?’

‘The money was to be paid in ten instalments….’

‘Never mind that,’ said Winter. ‘There was no message from Count Kupka?’

‘He said I was to give you his congratulations, Herr Winter. I imagine that…’

‘The baby,’ supplied Winter, although he knew that Count Kupka did not send congratulations about the birth of babies. Count Kupka obviously knew everything that happened in Vienna. Sometimes perhaps he knew before it happened.

‘My darling!’ said Winter. ‘Forgive me for not being here earlier.’ He kissed her and glanced round the room. He hated hospitals, with their pungent smells of ether and disinfectant. Insisting that his wife go into a hospital instead of having the baby at home was another grudge he had against Professor Schneider. ‘It’s been the most difficult of days for me,’ said Winter.

‘Harry! You poor darling!’ his wife cooed mockingly. She looked lovely when she laughed. Even in hospital, with her long fair hair on her shoulders instead of arranged high upon her head the way her personal maid did it, she was the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen. Her determined jaw and high cheekbones and her tall elegance seemed so American to him that he never got used to the idea that this energetic creature was his wife.

Winter flushed. ‘I’m sorry, darling. I didn’t mean that. Obviously you’ve had a terrible time, too.’