По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

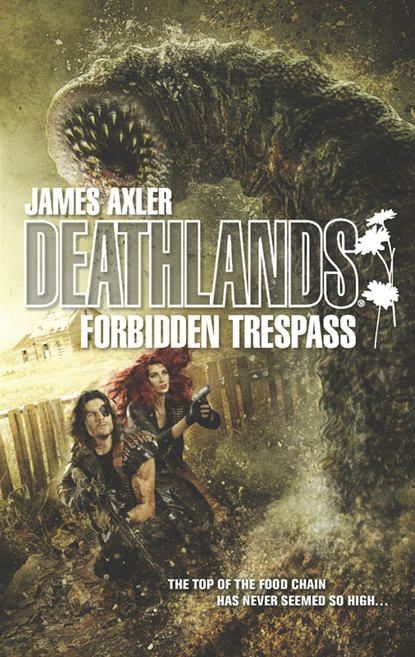

Forbidden Trespass

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He shoved her away, and she went down on her not-so-well-upholstered fanny so hard her tailbone cracked against the floorboards like a knuckle rapping on a table.

Scowling, Conn put down the bottle of shine he held and started around the bar, reaching under the counter as he did so.

The woman jumped to her feet. “What the nuke, you fat slob?”

“Back up off the triggers of them blasters, everybody,” a deep voice boomed from another corner of the room.

It was naturally arresting. Everyone stopped—even Conn himself, whom Ryan had observed in their previous visits was the unquestioned master in his own house.

The speaker wasn’t tall, but he was wide. A black man, the gray in his short, tightly curled hair showed him to be in middle age. And while he had a bit of a gut bulging out onto his thighs as he sat nursing his brew, Ryan suspected there was more muscle than flab. He was surrounded by four men and two women, most of whom showed a family resemblance, though it was far less pronounced than in the three largely chinless, large-foreheaded types who accompanied the meatbag.

“Don’t take it to heart,” he said calmly. “You’re new in these parts and don’t know. Them Sumzes don’t ball nobody more distantly related than first cousin. And Buffort, there, ain’t the sharpest tool in the shed.”

“It’s a family turdition, Tarley,” said a skinny redheaded Sumz with ears like open wag doors. “Dates back to the dark times. That’s how us Sumzes pulled through.”

Buffort guffawed and pounded a beefy fist on the table. It happened to be the one clenching the handle of his mug. Frothy brown beer slopped forth.

Ryan could smell him and his brothers from twenty feet away. The Sumzes were turpentiners, he knew—they made the stuff from the resin of loblolly pines growing around the valley where they made their home. Its astringent, piney smell overwhelmed even the body reek wafting from the group, and the fresh-sawdust-and-old-vomit stink that even the best-kept-up gaudy sported. It was even noticeable over the odor of the lanterns, which like most of the lamps hereabouts burned a blend of the pine oil with wood alcohol.

“You tell ’em, Yoostas!” the huge fat man crowed in a surprisingly shrill voice. “Family that sleeps together keeps together!”

Everybody laughed. Even the gaudy slut, though she looked as if she wasn’t clear as to the why.

A couple of husky young men, one dark-skinned, one light, had appeared near the scene. They were local youths Conn employed for odd jobs, including bouncing the occasional rowdy patron. They looked now to their boss.

He sighed, but he was already withdrawing his hand from underneath the bar. He used it to smooth back his thinning seal-colored hair instead.

“Right,” he said. “Keep a tighter leash on your boy, there, Yoostas.”

“Aw, c’mon, Conn. There ain’t no harm to him.”

“I know,” Conn said, moving back to his accustomed spot and picking up his bottle again, as if he meant to use it for its original purpose instead of cracking heads. “That’s why y’all are still here.”

He looked at the girl, who was trying to untangle her arms and upper torso from her ratty makeshift boa.

“Go take a break, Annie,” he said. “Catch a breath, pull yourself together.”

“But my take for the evening—”

“I said, take a break. I won’t jam you on the take. Don’t bleed when you’re not cut.”

She bobbed her head and vanished toward the back, where the few cribs were. Like a lot of the more respectable gaudy-house owners, Conn allowed a few women, usually down-on-their-luck locals, to rent time and space to ply their sexual wares rather than keeping them in greater or lesser degrees of slavery, as most did. Ryan had also noted he treated his workers the way he did trading partners: politely, calmly and driving a hard bargain but a fair one.

He didn’t cheat too much, which made him a Deathlands paragon.

Ryan turned his attention back to his friends. He saw them all easing their hands back from their own blasters. Handblasters only; Conn insisted longblasters be checked at the door. That chafed J.B.’s butt a tad, but Ryan went along with it, meaning the Armorer and the others did, too.

Ryan was willing to rely on Conn’s unwavering insistence on keeping an orderly house.

And if that failed, it wasn’t as if Ryan and his friends weren’t packing enough heat to burn a way to the little cabinet by the door where their longblasters were.

“There are worse places,” Mildred said with a shrug.

J.B. showed her a hint of sly grin. “You still got your mind on settling down?” he asked.

She shrugged her shoulders. “We’ve been in way worse locations, is all I’m saying.”

“Indeed,” Doc said. He was leaning forward, staring down at an angle at the tabletop with an unfocused look in his blue eyes. Ryan couldn’t tell for sure if he was agreeing with Mildred, or with some randomly remembered person from his past, like his long-lost wife, Emily, or even their children, Rachel and Jolyon. The predark whitecoats and their malicious time-trawling had done more than age him prematurely. Sometimes Doc lost touch with the present and wandered off through the fog of his own reminiscences.

The others couldn’t help but fear that sometime he might just wander off inside his own skull and never come back. But he always had, and lately things seemed to be getting consistently better. In any event he always snapped right to when the hammer came down.

Jak was frowning.

“What’s the matter, Jak?” Krysty asked gently.

The albino’s scowl deepened. But he didn’t snap back at her, as he sometimes could with his male companions. He just pressed his scarcely visible white lips together so hard they vanished altogether, and shook his head briskly.

“Don’t gnaw your own guts over not being able to track those stick-throwing white things,” J.B. said. As was his custom, he didn’t raise his voice. If he had something to say, he said it calmly. If he had something to do, he did it without hesitation or qualm. “They know the lay of the land better than even you can, most likely. And they probably have some kind of lairs nearby they can duck into.”

Though the gaudy chatter had resumed its normal volume, Ryan could hear Jak growl low in his throat. It wasn’t a gesture of hostility but a sign of his own dissatisfaction with himself.

“Listen, Jak,” Mildred said helpfully. “There’s always someone better than you.”

That got her a red-eyed glare.

“Mildred,” Ryan said dryly, “stop helping.”

The door burst open.

For a moment all that poured inside was darkness and the sound of crickets, audible because the dramatic opening had quieted the small talk again. It wasn’t necessarily in anticipation of an equally dramatic entry; people hereabouts, like most places, were just that starved for something a little different from the day-in, day-out routine.

But they got the drama anyway. A young woman came through the door, half striding, half staggering under a burden of deadweight and fatigue. She carried a body in her arms. It was apparently a child, a girl by the long hair that hung down from the intruder’s right arm, and she was dead, from the lifeless swing and dangle of her small, bare arms.

But the young woman’s head was high, black hair falling in waves around broad shoulders, one bared by her half-torn-open flannel shirt. Her deep blue eyes blazed with rage.

“My baby sister’s dead!” she cried in a vibrant voice. “Blinda’s been murdered, and I saw who done it!”

A number of patrons had jumped to their feet. “Who did it, Wymie?” one asked.

She fixed Ryan with a laser glare. “Those stoneheart outlanders there!”

That silenced the rising murmur as though cutting it off with an ax. Immediately whispers started up again: “Oh, holy shit, her face.”

Ryan saw that it was missing. Something had taken much of the bone from brow to lower jaw along with flesh and skin.

Ryan heard Krysty gasp. Doc made a strangled noise.

“You can’t be talking to us,” Ryan said, as evenly as he could.