По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

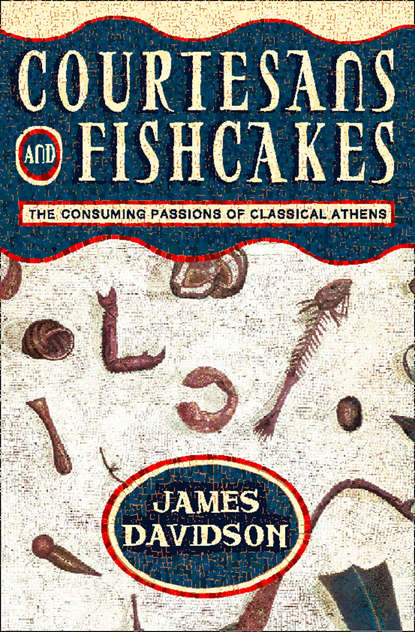

Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

COVER (#uac43cdef-ef51-5c78-81b4-500656d825cd)

TITLE PAGE (#u5f99a996-0948-5eeb-a688-8c57d3a68ec3)

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION (#u4ed27030-9762-5fab-b42f-687114e26f47)

INTRODUCTION

PART I. FEASTS

I Eating

II Drinking

PART II . DESIRE

III Women and Boys

IV A Purchase on the Hetaera

PART III . THE CITIZEN

V Bodies

VI Economies

PART IV . THE CITY

VII Politics and Society

VIII Politics and Politicians

IX Tyranny and Revolution

CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NOTES

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Introduction (#ue1250ee1-677e-5524-9669-fb8a886cef2d)

IN THE COLLECTION of the Vatican Museums is a mosaic signed by one Heraclitus. Across a white background is an even scattering of debris: a wish-bone, a claw, some fruit, various discarded limbs of sea-creatures, the remains of a fish. It is a copy of a famous mosaic by the artist Sosos of Pergamum, called the Unswept Hall. Sosos, whom the Roman antiquarian Pliny called ‘the most renowned’ of all mosaicists, worked in the first half of the second century BCE. He specialized in illusionistic works, trying to turn the unpromising medium of coloured tiles into something lifelike and real. His most famous and remarkable work depicted doves drinking from a birdbath. You could even see their reflections on the surface of the water, says Pliny. A copy was discovered at Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli. It is indeed a fine example of what ancient artists were capable of, achieving a very real sense of the basin’s three-dimensional form and burnished metallic sheen. What is so remarkable, however, about the Unswept Hall, is not its illusionistic ambition, but its objective humility. It is a floor that depicts a floor, closing the gap between art and life. This is most obvious, perhaps, with the white tiles, which have a perfect identity with the white tiles of an unswept floor. More honest than the sipping doves, on one level it really is what it claims to be; it is a trick-floor, impossible to clean.

But the floor is not really the subject at all. The true theme is an unseen banquet, as we can tell from the strewn litter. And this feast still seems to be going on. There was a pause in Greek banquets between the eating part and the drinking part of the meal, when tables were cleared, floors swept, hands washed and perfumes splashed. Sosos’ banquet has not quite reached that stage. Moreover, some of the debris casts rather strange shadows as if it is hovering half a millimetre above the ground, as if it has a little way still to fall.

The subject of this book is similar to Sosos’ – not the ancient banquet exactly, but the pleasures of the flesh that were indulged there: eating and drinking and sex. These are the consuming passions, three varieties of bodily gratification to which the whole human race, according to Plato, was susceptible from birth. Aristotle described them as animal cravings: hunger, thirst and lust, base and servile urges with their true foundation, contrary to appearances, in the sense of touch. This accounts for the gourmand, he says, who prayed for the throat of a crane so he could enjoy his food for the longest time, as it travelled slowly down. More exactly, this book is about the pleasures of the flesh in classical Athens, because although not all the material I have used falls inside the classical period (479–323 BCE – Before the Common Era) and a little of it is not even pure Athenian, it is Athens and the Athenian democracy that provide the context.

Its material is the scraps that have fallen from the tables of ancient literature, snatches of conversation, anecdotes abruptly curtailed and stories that seem to make no sense: an explorer comes across a savage tribe on the shores of the Persian Gulf who live off bread made from fish and ‘fishcakes’ for special occasions; the philosopher Socrates visits a beautiful woman who lives in luxury with no visible means of support and refers obliquely to ‘her friends’; the guests at a drinking-party imagine they are at sea and throw furniture out of the windows to prevent their boat from capsizing; a politician makes a speech about towers and walls and finds himself accused of prostitution; a tyrant finds a lost ring inside a magnificent fish and thinks he recognizes the work of the gods, but when he tells the King of Egypt he immediately breaks off their friendship; the general Alcibiades drinks wine without water, countless statues of Hermes are vandalized in the night and Athens loses the Peloponnesian War.

One particular table has provided especially rich pickings, Athenaeus’ Dinner-sophists or Banquet of Scholars, composed at the turn of the second century of the Common Era (CE), a long work in the form of a dialogue in the tradition of Plato’s Symposium. Instead of discussing the meaning of life or the nature of love, however, Athenaeus’ guests talk only of the banquet itself, of different kinds of food and wine, of famous courtesans and boastful chefs, of cups and riddles, of a league-table of luxurious nations. They are hardly interested in their own period, concentrating on the world before the Romans arrived, particularly the world of classical Athens which had succumbed to an army of Macedonians five hundred years before. Most importantly, the guests are astonishing pedants, bolstering the most trivial comments with a formidable array of quotations from ancient literature, literature which has now almost entirely disappeared.

Very few scholars are interested in Athenaeus himself and his pernickety banquet, but the scraps from his table provide a unique resource for historians of pleasure. Ancient historians often find themselves relying on only one author for matters of the greatest importance. Thanks to Athenaeus, however, those who wish to know what the Greeks thought of crustaceans, or of various courtesans, or of the proper way to drink wine, can draw on a huge number of authors and a wide range of genres. Of course Athenaeus has his own clear predilections and his selection must not be seen as a representative cross-section of Athenian culture or Athenian literature in general. He draws especially on the comic poets and it is Attic comedy, produced each year at festivals of Dionysus, that provides the basis for much of what we know of Athenian life. Unlike the tragedies which gave up on the present early in the classical period, comedy was very much about the contemporary world and contemporary issues. It often named contemporary politicians and public figures or featured them in its plots, resorting to the world of myths and heroes only in order to parody tragic rivals or to set up incongruous juxtapositions between then and now.

Comedy is not the only source, however, for Athenian pleasures. We also have a large number of speeches covering the period from the late fifth century to the late fourth in the corpus of the ‘Attic Orators’, the top ten classical rhetoricians, selected by later critics as suitable models for emulation and preservation – plus a few others who managed to slip incognito through the canon’s net. Most of these speeches are forensic, attacking enemies in the law-courts or trying to provide a feasible defence. Some are deliberative, speeches on public policy delivered in the Assembly. A few are epideictic, demonstration pieces, designed to show off the speaker’s skill. Because of their context they present a very different perspective on pleasure from the festive comedies, emphasizing the dangers that appetite presents to the household and the city and to fellow-citizens; not their own appetites of course, but those of their enemies.

Apart from these sources, there are a large number of miscellaneous works preserved in Athenaeus or independently; treatises and pamphlets on various themes, including one very famous manual of sex and seduction by Philaenis, a classical Kama Sutra, of which, sadly, only the barest scraps survive. There are also a large number of anecdotal works by the likes of Lynceus of Samos and Machon, who collected the witticisms of courtesans and put them in verse. Chief among these anecdotal works, perhaps, is Xenophon’s Memoirs, in which the philosopher Socrates discourses on various issues of everyday life, advising the author against kissing a handsome boy, and engaging the mysterious beauty, Theodote, in conversation.

It might be thought that such an interesting subject, fundamental as well as sensational, with such a wealth of material to work with, must have been thoroughly investigated long ago, but this is far from being the case. Even now there is considerable resistance to an area of ancient studies which is seen as no more than light relief between papers on more important topics. It is true that this kind of antiquarian/philological research into customs and lifestyles has a rather longer pedigree than other branches of ancient history. Isaac Casaubon, whose notes on Athenaeus first appeared in 1600, can still be useful to modern researchers. On the other hand, since the beginning of the twentieth century, and especially since the Second World War, there has been an astonishing decline in interest in the subject among professional historians. In part their attention has been absorbed by archaeology and inscriptions, which often have a more straightforward relationship to the ‘Real World’ than fantastical authors such as Aristophanes or unreliable gossips such as Lynceus, and which often carry with them the kudos of new discoveries. Material objects, documents and ‘solid facts’ carry a kind of mystical objectivity for many historians, constituting what some refer to as the ‘meat and potatoes’ part of history. In fact, some historians are so distrustful of airy-fairy texts and soufflés like Athenaeus, they would rather not use them at all, trusting only to silent stones, ground-plans and artefacts when conducting their research – as well as large doses of their own (objective) intuition. Ancient history, however, is not so rich in resources that it can afford to ignore any of them. A neglected or misused text is as much a lost artefact as something buried several feet underground.

While scholarly attention has been distracted elsewhere, some extraordinary gaps have been allowed to open up in our knowledge of ancient culture and society. The lack of work on Greek hetero-sexuality and (until recently and outside France) ancient food are particularly striking. I can only think that prostitutes and courtesans are not considered worthy of women’s history or that they have been overlooked in the belief that Greek homosexuality was more significant or important. Even at the end of this research I am left not with a sense of satisfaction that the material is exhausted, but with the realization that much is still preliminary and an anxiety about how much remains to be done. Anyone with time on their hands and a desire to make a substantial contribution to human knowledge will find few more promising areas of investigation than Greek bring-your-own ‘contribution-dinners’, Attic cakes, the ‘second’ dessert table, the consumption of game, gambling, perfumes, flower wreaths, hairstyles, horse-racing, pet birds and all the various entertainments of the symposium, including slapstick, stand-up comedy and acrobatics. The only necessary qualification would be a willingness to take these subjects seriously (not too seriously), since they are worth much more than a superficial survey. With the comic fragments recently edited and judiciously annotated by Rudolf Kassel and Colin Austin, there is no longer any excuse.

I mention the general neglect of this area of ancient studies in part to correct a common and rather bizarre misapprehension that sex and other indulgences have received more than their fair share of scholarly attention in recent years and to crave the reader’s indulgence for my notes. It has occasionally been necessary to spend time and space establishing some very basic facts which have to be argued for and supported with citations from ancient texts, before going on to the more interesting task of drawing out their implications, suggesting solutions and putting them in context, the main role of the second half of the book. However, those who get impatient with the spade-work can comfort themselves with the thought that they are at the cutting edge of this soft subject.

To be fair, one problem with this kind of research has always been that the evidence is rather slippery and difficult to handle. Historians of the ancient world prefer to work with honest-seeming, authoritative sources, such as Thucydides or Polybius who seem to have done their homework properly. Greek comedy, on the other hand, though it was clearly dealing with the real world, was far from straightforwardly realistic, as anyone will know who has attended a performance of one of Aristophanes’ plays. This means we have to approach comic fragments with caution to see whether they are referring to an everyday situation or some fantastic scenario. If a comic poet talks of a law to stop fishmongers drenching their fish with water to make them look fresher than they really are, do we imagine there really was a law at Athens to that effect, or rather that a law has been passed in the play because of some imaginary crisis (the Clouds boycotting Athens, Zeus on strike, or the goddess Truth taking over the city)? On the other hand, it is often in the most extravagant images that the most powerful insights into Athenian society are found. Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae, for instance, a satire on women seizing power, opens with the ringleader addressing a lamp, the trusty confidante of women’s secrets and witness to their adulteries, whose silence alone they trust. Few would consider Athenian women ever seriously contemplated a revolution or that they ever spoke to their lamps. Nor is it likely that they were engaged in endless bouts of sex with forbidden lovers. On the other hand, the address to the lamp throws light on various aspects of Athenian life and culture that can be confirmed from elsewhere: that the sexes were often segregated, that men looked on women as rather mysterious creatures, that the segregation carried an erotic charge, that women had to be extremely careful if they broke the sexual rules, that sexual insubordination and political insubordination could be linked in the imagination and on stage.

Speeches too have their pitfalls. Standards of proof were rather low in Athenian courts and truth was not necessarily placed at a premium. Modern scholars are extremely doubtful that the events are as the orators describe. They suspect orators of inventing laws, lying about their opponents’ families and status, lying about their age. One prosecutor positively boasts that he has no evidence for his accusations apart from rumour, whose testimony he praises to the skies. On the other hand, we know that the defendant against whom rumour testified was convicted and although the orators are unreliable witnesses of what went on in Athens, they are excellent witnesses of what was thought convincing. We may not really believe that a man could ‘spend an entire estate on affairs with boys’ or that the largest fortune in Greece could evaporate because of expensive parties and women, but the Athenians certainly did believe these things and that is interesting in itself.

It will be clear from this that ultimately the subject of this book is not so much the pleasures of the flesh themselves, but what the Greeks, and especially the Athenians, said about them, the way they represented them, the consequences they ascribed to them, the way they thought they worked. Instead of looking at the ancient sources as windows on a world, we can see them as artefacts of that world in their own right. We know that the Unswept Hall is not an accurate representation of the floor of a banquet. The randomly scattered rubbish is in fact not random at all, but evenly spaced, and contains a bit of everything without the repetitions and haphazard accumulations we would expect. But even though the picture is ‘wrong’, it might tell us a lot about the importance of banquets in the ancient world, the nature of realism, the notion of extravagance, of randomness; the artist’s ‘error’ might even give insights into why the lottery was made the linchpin of Athenian democracy. If, to take another example, a particular poet describes a courtesan as whorish, greedy and deceitful, it is rather difficult to decide now whether his assessment was accurate. On the other hand, we know for sure that it is very good evidence for the way courtesans were represented on stage. Alexander the Great may or may not have died from taking a massive swig of wine, but many Greeks said he did, and their ideas about the effects of wine are what concern us.

This kind of investigation is known as the study of discourse, a term popularized by the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault. Discourse is more or less the same thing as ‘attitudes’, if we allow that term its full balletic implications of posturing and plurality. In Greece, above all, where the sophists had made praising gnats, playing devil’s advocate and arguing black was white a national sport, it would be dangerous to take our sources as good evidence even for their own views, but what is interesting about Foucault’s work is the realization that misrepresentations are just as interesting as representations, and even more useful, when you can identify them, are outrageous lies.

Critias, for instance, a right-wing philosopher and a leader in the oppressive regime imposed on Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War, is almost certainly lying when he says the Spartans drank only water from their mug-like cups. If this was no more than a personal idiosyncrasy we could not draw any broader conclusions, but his little lie is part of a pattern we find in other authors who spend time and effort defending Spartan institutions, their effeminate long hair, their fancy cloaks dyed Tyrian purple. A whole host of other sources, moreover, seem to contradict Critias directly, representing Spartan cups as the kind of cups used for the most degenerate kind of drinking: strong wine, greedy swigs, drinking solely to get drunk as quickly as possible. Critias is clearly participating in a debate defending the Spartan reputation for asceticism in the face of the quite different reputation acquired in Athens by their cups.

These debates over Sparta and over the right way to drink, carried on by many different authors over a long period of time, are like super-discourses, a kind of generalized conversation carried on within Athenian culture, of which Critias’ extraordinary defence of Spartan cups is merely a particular exemplar. These ideal and repetitive debates are, for some cultural historians, the real object of historical investigation, and individual texts mere instances.

Historians not only use texts as windows, sometimes they assume that is their purpose too, as if the Greeks wanted to give us a view on the ancient world, to let posterity see what they were like, as if the real audience is not the audience sitting in the law-courts or the theatre, but us. Very occasionally, this view is fair enough. Thucydides wanted to put down the most accurate record of the war he lived through and intended his history to be a ‘possession for all time’ which includes us, even though he may not have been thinking quite so far ahead. People produce images and texts for all kinds of reasons, for beauty, for art itself, to make a living, to commemorate, to amuse, to create an atmosphere, as therapy and so on. It seems fair to say, however, that in Critias’ case it is the debate about Sparta that causes him to put pen to paper. He is intervening in a controversy. He is a propagandist, a pamphleteer. The debate, the problematization of Sparta, or of Spartan cups, comes first. The texts are symptoms of that controversy. This way of looking at our sources leads to some strange conclusions: the more people talk about something, the more contentious that subject was, the less of a consensus there was about it. Far from reflecting the way the Greeks normally spoke, texts are often arguing uphill, insisting on a point of view that few of their contemporaries would share. The text is produced to change minds. By the same argument, the most obvious and unquestioned things may never make it into texts at all. We hear very little, for instance, of how the Greeks ate their food, because it involved a set of banal practices that no one considered worthy of remark. In the case of appetites, we hear much more about dangerous activities than about everyday consumption.

Often, then, what looks like the most promising evidence, addressing a question directly, turns out to be the least trustworthy. When an orator stops in mid-speech to tell his audience the difference between wives, concubines and courtesans, we should be immediately on our guard. When a philosopher provides us with a useful definition of what a gourmand really is, we should resist the temptation to copy it into our dictionaries. Foucault himself seems to have forgotten this useful principle in his own study of sexuality, which is overwhelmingly dependent on philosophical and prescriptive texts which set out to tell him the answers. He seems to have thought that even if these sources were unreliable witnesses of what went on, they were good representatives of Greek concerns with sexuality. They were not. Foucault’s study of Greek sexuality has very little on women at all and gives the impression the Greeks were much more interested in boys. Any examination of comic fragments, vase-paintings and Attic oratory, however, shows this impression is quite false, a Platonic mirage. Philosophers are often useful, devoting more space to pleasure and working towards a deeper analysis, but they feature rather less in this book than in other studies of Greek attitudes and when they do appear, some context is sought to measure the angle and spin on what these tricksters are saying.

The shift from using texts as windows to using texts as artefacts in their own right has rescued the study of ancient pleasure from endless arguments about reliability and the ‘rhetorical topos’ or cliché. Private life has by its nature fewer witnesses than battles and political debates and there are fewer checks on lies and misrepresentations. The discourse of private life on the other hand is eminently public. Much of our evidence comes from central areas of debate, the theatres and law-courts, from the hill of the Pnyx itself where the Athenian Assembly met. The audiences it was supposed to amuse and persuade were numbered in their thousands. Moreover, in this context, statements gain meaning instead of losing it when they are found repeated elsewhere by other authors. Instead of dismissing such things as mere commonplaces that mean nothing apart from the speaker’s hostility, admiration or contempt, we can put them together, making connections, working out their mechanisms, illuminating patterns of debate. We can even construct little narratives of pleasure with their own implied beginnings and their own augured ends. We can try to see if our author is relating a casual consensus or casually trying to defend a sticky wicket and, thanks to Athenaeus, the conclusions we draw about what Athenians talked about and wrote about will be more reliable, since the statements have come from many different authors and have been exposed to a wide audience. We know next to nothing about Plato’s audience, by contrast, and he may be, and sometimes clearly is, a testament only to his own (very interesting) self.

We can, however, sometimes go too far with discourse and start fetishizing it as a new reality. Foucault and his followers often run into trouble on three counts especially. Although he is interested in ancient debates and not some single ‘ancient view’, the debate is often conceived too narrowly and rigidly. What the Greeks said about pleasure is much messier and much more varied than what you would expect from Foucault. Secondly, on the basis of this narrow and rigid idea of discourse, human history has been divided into discrete ages (often making sense only in France) or epistemes separated by world-shattering intellectual revolutions that open up great chasms in time. Each of these epistemes is viewed as a crystal that must be shattered before a new episteme is crystallized again in a quite new age. Originally the theory was applied only to the category of knowledge and used to account for a culture’s peculiar blind-spots and fantasies. In his later work on sexuality, however, and in the work of his followers, it was applied more generally. Greek civilization, according to this interpretation, is an irretrievably alien culture, constituting a separate sealed world with its own peculiar possibilities for experience. Finally, in fetishizing a culture’s representations of the world in this way, Foucault and his followers sometimes seem to forget about the world itself, which is still waving through the window, as if what a culture says is, is, on some important level, as if the Greeks walked around in a virtual reality they had constructed for themselves from discourse.

One very popular theory about the Greeks, for instance, showing the influence of Freud and de Beauvoir as well as Foucault, claims that the Greeks divided the world up into two parts, Them and Us. Us being the adult male citizens who wrote all the texts, Them being the others or Other, slaves, women, barbarians and so on who didn’t. Foucault unfortunately incorporated this Manichaean view into his history of sexuality. With Us cast as the penetrators, Them the penetrated. This absurd oversimplification predictably produces very banal self-fulfilling results. That slaves are like women, that women are like slaves, that slaves have automatically lost their phalluses, and are all always metaphorically penetrated by their masters, that everything is whatever the adult male citizen says it is. While it is true that the Greeks often talked about the world in binary terms as polarized extremes, this was simply a way of talking and thinking about things (and not the only way), while the terms of the opposition might change all the time. Sometimes they talk about Greeks versus Persians, sometimes about Persians versus Scythians, and the representation of what the Persians are will be transformed accordingly. Likewise, sometimes they talk about women in terms of an opposition between common prostitutes and wives. In the next sentence, however, the terms of the polarity might have changed. The distinction is now between flute-girls and courtesans, or concubines and hetaeras. This Black and White way of arguing does not reflect a Manichaean view of the world.

There are two main dangers in approaching the Greeks. The first is to think of them as our cousins and to interpret everything in our own terms. We are entering a very different world, very strange and very foreign, a world inconceivably long ago, centuries before Christ or Christianity, a century or so before the first Chinese emperor’s model army, a world indeed without our centuries, or weeks or minutes or markings of time. And yet these Greeks will sometimes seem very familiar, very lively, warm and affable. Occasionally we might even get their jokes. We must be careful, however, that we are not being deceived by false friends. Often what seems most familiar, most obvious, most easy to understand is in fact the most peculiar thing of all. On the other hand, we must resist the temptation to push the Greeks further into outer space than is necessary. They are not our cousins, but neither are they our opposites. They are just different, just trying to be themselves.