По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

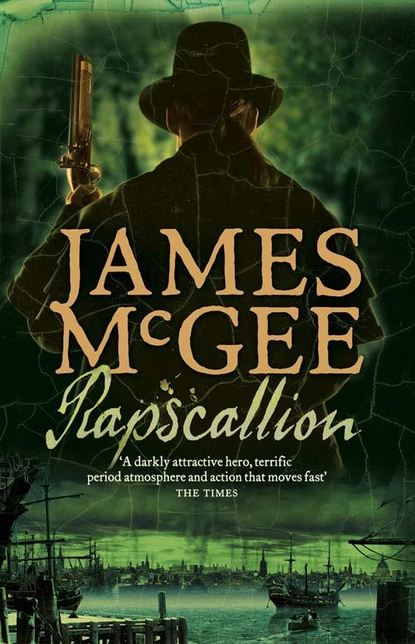

Rapscallion

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Captain?” Hawkwood prompted.

Ludd ceased chewing. “He was not the first,” he said heavily.

Hawkwood sensed James Read shift in his seat. Ludd continued to look uncomfortable. “The first officer we sent, a Lieutenant Masterson, died.”

“Died? How?”

“Drowned, it’s presumed. His body was discovered two weeks ago on a mud bank near Fowley Island.”

“Which is where?” Hawkwood asked.

“The Swale River.”

“Kent.”

Ludd nodded. “At the time there was nothing to indicate he’d been the victim of foul play. We mourned him, we buried him, and then Lieutenant Sark was dispatched to continue the investigation.”

“But now that Sark’s failed to report back, you’re thinking that perhaps the drowning wasn’t an accident.”

“There is that possibility, yes.”

“Forgive me, Captain, but I still don’t see what this has to do with Bow Street,” Hawkwood said. “This remains a navy matter, surely?”

Before Ludd could respond, James Read interjected: “Captain Ludd is here at the behest of Magistrate Aaron Graham. Magistrate Graham is the government inspector responsible for the administration of all prisoners of war. He reports directly to the Home Secretary. It was Home Secretary Ryder’s recommendation that the Board avail itself of our services.”

Hawkwood had met Home Secretary Richard Ryder and hadn’t been overly impressed, but then Hawkwood had a low opinion of politicians, irrespective of rank. In short, he didn’t trust them. He had found Ryder to be a supercilious man, too full of his own importance. He wondered if Ryder had been in contact with James Read directly. There was nothing in the Chief Magistrate’s manner to indicate he was talking to Ludd under sufferance, but then Read was a master of the neutral expression. It didn’t mean his mind wasn’t whirring like clockwork underneath the impassive mask.

Read got to his feet. He walked to the fireplace and adopted his customary pose in front of the hearth. The fire was unlit, but Read stood as if warming himself. Hawkwood suspected that the magistrate assumed the stance as a means to help him think, whether a fire was blazing away or not. Oddly, it did seem to imbue an air of gravity to whatever pronouncement he came up with. Hawkwood wondered if that wasn’t the magistrate’s real intention.

Read pursed his lips. “It’s no secret that the Board has come in for a degree of criticism over the past twelve months. It has been the subject of two Select Committees. Their findings were that the Board has not performed as efficiently as expected. Further adverse reports would be most … unhelpful. So far, these escapes have been kept out of the public domain. There’s concern that, should word of its inability to keep captured enemy combatants in check emerge, the government’s credibility could suffer a severe blow. With all due deference to Captain Ludd, while the loss of one officer sent to investigate these escapes might be construed as unfortunate, the loss of two officers could be regarded as carelessness. It is all grist to the mill, and with the nation at war any lack of confidence in the administration could have dire consequences.”

Hawkwood stole a glance at the captain and felt an immediate sympathy. He knew what it was like to lose men in battle; he himself had lost more men than he cared to remember, and it was a painful burden to bear.

“What services?” Hawkwood asked.

Read frowned.

“You said the Home Secretary wants the Board to avail itself of our services. What services?”

James Read looked towards Ludd, who gave a rueful smile. “My superiors are unwilling to commit further resources to the investigation.”

“By resources, you mean men,” Hawkwood said.

Ludd flushed. “As Magistrate Read stated, two officers have apparently fallen prey to the investigation already. I am not anxious to dispatch a third man to investigate the death and disappearance of the first two.”

Everything became clear. Hawkwood stared at James Read. “You want Bow Street to take over the investigation?”

“That is the Home Secretary’s wish, yes.”

“What makes him think we can succeed where the navy has failed?”

Read placed his hands behind his back. “The Home Secretary feels that, while the Admiralty is perfectly capable of assigning officers to the field, there are certain advantages in utilizing non-naval personnel, particularly in what one might consider to be investigations of a clandestine nature.”

“Clandestine?”

“There are avenues open to this office that are not available to other – how shall I put it? – more conventional, less flexible departments of government. Would you not agree, Captain Ludd?”

“I’m sure you’d know more about that, sir,” Ludd said tactfully.

“Indeed.” The Chief Magistrate fixed Hawkwood with a speculative eye.

An itch began to develop along the back of Hawkwood’s neck. It wasn’t a pleasant sensation.

“I refer to the art of subterfuge, Hawkwood; the ability to blend into the background – most useful when dealing with the criminal classes, as you have so ably demonstrated on a number of occasions.”

Hawkwood waited for the axe to fall.

“Captain Ludd and I have discussed the matter. Based on our discussion, I believe you’re the officer best suited to the task.”

“And what task would that be, sir … exactly?”

James Read smiled grimly. “We’re sending you to the hulks.”

The Chief Magistrate’s expression was stern. “We’ve got prisoners of war spread right around the country, from Somerset to Edinburgh. Fortunately for us, the new prison in Maidstone is ideally situated for our purposes. It’s been used as a holding pen for prisoners prior to their transfer to the Medway and Thames hulks. You’ll begin your sentence there. From Maidstone you’ll be transported to the prison ship Rapacious. She’s lying off Sheerness. Better you arrive on the hulk within a consignment of prisoners rather than alone. There’s no reason to suppose anyone will question your credentials, but it should give you an opportunity to form liaisons with some of your fellow internees before embarkation.”

It was interesting, Hawkwood mused, that the Chief Magistrate had used the word sentence rather than assignment. Perhaps it had been a slip of the tongue. Then again, he thought, maybe not.

“Your mission is several fold,” Read said. “Firstly, you are to investigate how these escapes have been achieved –”

“You mean you don’t know?” Hawkwood cut in, staring at Ludd.

Ludd shifted uncomfortably. “We know Rapacious has lost four prisoners in the past six weeks. The trouble is, we don’t know the exact time the losses took place. We can assume the other prisoners concealed the escapes from the ship’s crew, possibly by manipulating the roll count. Without knowing the precise times of the escapes we haven’t been able to pin down how they were achieved, whether it was a spur-of-the-moment thing based on a lapse in our procedures or if the escapes were planned and executed over a period of time. All we know is that Rapacious is missing four men. What makes it more interesting is that there have been similar losses from some of the other Medway-based ships. We’re also missing a couple who broke their paroles.”

“How many in total?” Hawkwood asked.

“Ten unaccounted for.”

“Over how long a period?”

“Two months,” Ludd said.

“As I was saying …” James Read spoke into the pregnant silence which followed Ludd’s admission. “You are also to determine whether the escapers have received outside assistance. Captain Ludd is of the opinion that they have.”

“Based on what?” Hawkwood said.

“Based on the fact that we haven’t managed to track any of the buggers down,” Ludd said.

“Explain.”