По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

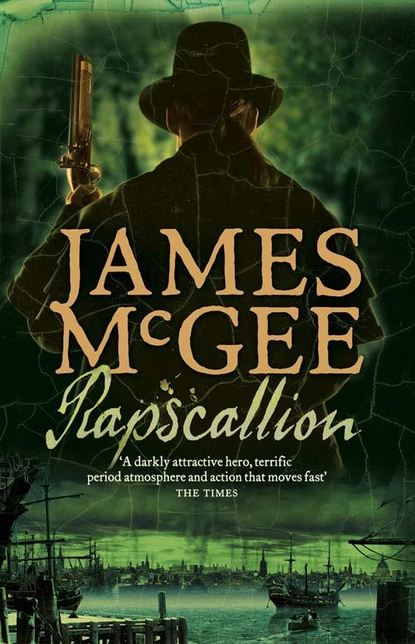

Rapscallion

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Here they come,” a man next to Hawkwood muttered. “Sons of bitches!”

“What’s happening?” Hawkwood asked.

The prisoner turned. His uniform hung off his bony frame. His hair was grey. A neat beard concealed his jaw. The state of his attire and the colour of his hair suggested he was not a young man, yet there was a brightness in his eyes that seemed out of kilter with the rest of his drawn appearance. He could have been any age from forty to seventy. He was clutching several books and sheets of paper.

“Inspection.” The prisoner looked Hawkwood up and down. “Just arrived?”

Hawkwood nodded.

“Thought so. I could tell by your clothes. The name’s Fouchet.” The prisoner juggled with his books and held out a hand. “Sébastien Fouchet.”

“Hooper,” Hawkwood said. He wondered how much pressure to apply to the handshake, but then found he was surprised by the strength in the returned grip.

Fouchet nodded sagely. “Ah, yes, the American. I heard we had one on board. You speak French very well, Captain.”

Jesus, Hawkwood thought. He didn’t recall seeing Fouchet in the vicinity of the weather-deck when his name had been registered. Word had got round fast.

“How often does this happen?” Hawkwood asked.

“Every day. Six o’clock in the summer, three o’clock in the winter.”

The guards proceeded to spread about the deck. There was no provision made for anyone seated on the floor, nor for the items upon which they might have been working. Hawkwood watched as boot heels crunched down on to ungathered chess pieces, toys and model ships. Ignoring the protestations of those prisoners who were still trying to retrieve their belongings, the guards proceeded to tap the bulkheads and floor with the iron clubs. When they got to the gun ports they paid close attention to the grilles. The deck resounded to the sound of metal striking metal. Hawkwood wondered how much of the guards’ loutish behaviour was for effect rather than a comprehensive search for damage or evidence of an escape attempt. Not that the strategy was particularly innovative. It was a tried-and-tested means of imposing authority and cowing an opponent into submission.

Satisfied no obvious breaches had been made in the hulk’s defences, the guards retraced their steps. Peace returned to the gun deck and conversation resumed.

“Bastards,” Fouchet swore softly. He nodded towards Lasseur and then squinted at the boy. “And who do we have here?”

Hawkwood made the introductions.

“There are other boys on board,” Fouchet said. “You should meet them. We’ve created quite an academy for ourselves below decks. We cover a wide range of subjects. I give lessons in geography and geometry.” Fouchet indicated the books he was holding. “If you’d like to attend my classes I will introduce you. It is not good for a child to while away his day in idle pursuits. Young minds should be cultivated at every opportunity. What do you say?” Fouchet gave the boy no chance to reply but continued: “Excellent, then it’s agreed. Lessons will commence tomorrow morning, at nine o’clock sharp, by the third gun port on the starboard side. Adults are welcome to attend too. For them, the charge is a sou a lesson.” He pointed down the hull and turned to go.

Lasseur placed a restraining hand on the teacher’s arm. “Did you see what happened to the men in the boat?”

The teacher frowned. “Which boat?”

“The one before ours; the one left to drift. The men were too weak to board.”

“Ah, yes.” The teacher’s face softened. “I hear they were taken on board the Sussex.”

“Sussex?”

“The hospital ship. She’s the one at the head of the line.” Fouchet pointed in the direction of the bow.

Lasseur let go of the teacher’s arm. “Thank you, my friend.”

“My pleasure. There’ll be another inspection in an hour, by the way, to count heads, so it wouldn’t do to get too comfortable. I’ll look out for you at supper. I can show you the ropes. In return, you can tell me the news from outside. It will help deflect our minds from the quality of the repast. What’s today, Friday? That means cod. I warn you it will be inedible. Not that it makes any difference what day it is; the food’s always inedible.” The teacher smiled and gave a short, almost formal bow. “Gentlemen.”

Hawkwood and Lasseur watched Fouchet depart. His gait was slow and awkward, and there was a pronounced stiffness in his right leg.

“Cod,” Lasseur repeated miserably, closing his eyes. “Mother of Christ!”

The next contingent of guards did not use iron bars. Instead, they used muskets and fixed bayonets to corral the prisoners on to the upper deck. From there they were made to return to the lower deck and counted on their way down. The lieutenant who had overseen the registration was in charge. His name, Hawkwood discovered, was Thynne.

The count was a protracted affair. By the time it was completed to the lieutenant’s satisfaction, shadows were lengthening and spreading across the deck like a black tide. In the dim light, the prisoners made their way to the forecastle to queue for their supper rations.

The food was as unappetizing as Fouchet had predicted. The prisoners were divided into messes, six prisoners to a mess. Their rations were distributed from the wooden, smoke-stained shack on the forecastle. Sentries stood guard as a representative from each mess collected bread, uncooked potatoes and fish from an orderly in the shack. The food was then taken to cauldrons to be boiled by those prisoners who’d been nominated for kitchen duty. Each mess then received its allocation. Fouchet was the representative for Hawkwood’s mess.

Lasseur stared down at the contents of his mess tin. “Even Frenchmen can’t make anything of this swill.” He nudged a lump of potato with his wooden spoon. “I shall die of starvation.”

“I doubt you’ll die alone,” Hawkwood said.

“It could be worse,” Fouchet said morosely. “It could be a Wednesday.”

“What happens on Wednesdays?” Lasseur asked, hesitantly and instantly suspicious.

“Tell him, Millet.” Fouchet nudged the man seated next to him, a sad-eyed, sunken-chested seaman whose liver-spotted forearms were adorned with tattooed sea serpents.

The seaman scooped up a portion of cod and eyed the morsel with suspicion. “We get salted herring.” Millet shovelled the piece of fish into his mouth and chewed noisily. He didn’t have many teeth left, Hawkwood saw. The few that remained were little more than grey stumps. Hawkwood suspected he was looking at a man suffering from advancing scurvy. Hardly surprising, given the diet the men were describing.

Lasseur regarded the man with horror.

“We usually sell them back to the contractor.” The speaker was seated next to Millet at the end of the table. He was a cadaverous individual with deep-set brown eyes, a hooked nose, and a lot of pale flesh showing through the holes in his prison clothes. “He gives us two sous. The following week, he returns the herring to us so that we can sell them back to him again. Most of us use the money to buy extra rations like cheese or butter. It helps take the taste of the bread away.”

Lasseur picked up a piece of dry crust. “Call this bread? This stuff would make good round shot. If we’d had this at Trafalgar, things would have been different.”

“What do you think the British were using?” Fouchet said. He lifted his piece of bread and rapped it on the table top. It sounded like someone striking a block of wood with a hammer. He winked at the boy, who up to that moment had been trying, without success, to carve a potato with the edge of his spoon. “Give it here,” Fouchet said, and solved the problem by mashing the offending vegetable under his own utensil. He handed the bowl back and the boy smiled nervously and resumed eating. He was the only one at the table not to have passed comment on the food.

“Do they ever give us meat?” Hawkwood asked.

“Every day except Wednesdays and Fridays,” Millet said, with a marked lack of enthusiasm. “Don’t ask what sort of meat it is, though. The contractors keep telling us it’s beef, but who knows? Could be anything from pork to porcupine.”

Fouchet shook his head. “It’s not porcupine. Had that once; it was quite tasty.”

Lasseur chuckled. “How long have you been here, my friend?”

Fouchet wrinkled his brow. “What year is it?”

Lasseur’s jaw fell open.

“I’m joking,” Fouchet said. He stroked his beard and added, “Three years here. Before this I was on the Suffolk off Portsmouth.” He jabbed a finger at the tall, hook-nosed prisoner. “Charbonneau’s been held the longest. How long has it been, Philippe?”

Charbonneau pursed his lips. “Seven years come September.”

Seven years, Hawkwood thought. The table fell quiet as the men considered the length of Charbonneau’s internment and all that it implied.

“Anyone ever get away?” Hawkwood asked nonchalantly. He exchanged a glance with Lasseur as he said it.

“Escape?” Fouchet appeared to ponder the question, as if no one had asked it before. Finally, he shrugged. “A few. Most don’t get very far. They’re brought back and punished.”