По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

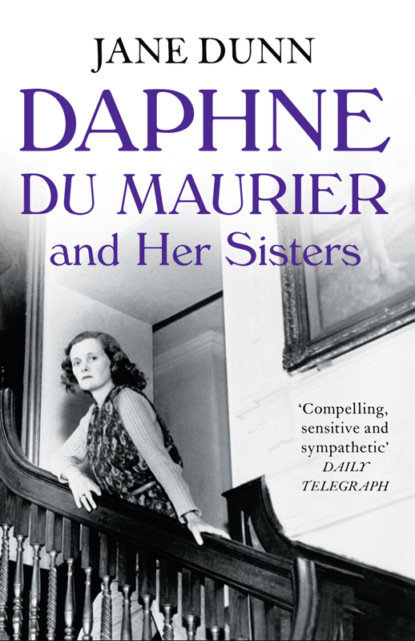

Daphne du Maurier and her Sisters

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Angela was a prolific writer of letters all her long life. She had many friends and acquaintances, but when she was old it seems that she wrote to her closest friends and asked them to destroy her letters. She had already burnt all her love letters, she explained to one of her past lovers, whose letters she had decided to keep. She also could not bring herself to burn her love poems to various important women in her life. For Angela, her deepest feelings and what made her happy in life, were in conflict with her desire to keep up appearances. She learnt early to dissemble to her parents. This conflict became more marked as she grew older, living within a close community in Fowey in Cornwall, where she was held in respect as ‘Miss Angela’, and attached to an Anglo-Catholic Church unsympathetic to any nonconformity in faith or life.

Despite this attempt to obscure her true self, two extrovert autobiographies, if read carefully, are full of hints of a larger life, a more independent and courageous attitude to love, than one might ever suspect from the conventional face she chose to present to the world. She did not want to be known for her guise as maiden aunt who had missed out on love. There had been much more to her than her Pekinese dogs and the roles of dutiful daughter, dependable friend and stalwart of Church and community. I hope this exploration of her life is in keeping with at least one aspect of her family’s ethos, for the sisters were much influenced by their own father’s view that a biography is only worth doing if it attempts to tell the truth without evasion or pretence. Daphne boldly followed this precept with her own memoir of her father, soon after his death, shocking some of his old friends with her temerity.

Whereas following Angela’s clues have led me on an intriguing journey of dead-ends and surprising revelations, the search for Jeanne has been blocked from the beginning of my researches. Her lifelong partner, the intellectual and prize-winning poet Noël Welch, still lives in their exquisite house on Dartmoor with the best collection of Jeanne’s paintings, all her papers and her memories. Now in her nineties, she has been adamantly set against any biography of the sisters, despite writing her own insightful piece on them for The Cornish Review nearly forty years ago. There are vivid glimpses of Jeanne in other people’s letters and memoirs. In the few letters that have surfaced, an expressive, amusing, highly creative voice rings out through the years as freshly as when they were written.

The du Maurier girls could not have been more closely brought up. They were consciously sheltered from the contamination of school; for them there was no escape where, freed from controlling adults, they might speak of taboo subjects like sex and God and money. Largely lacking outside friends, the sisters were thrown on each other’s company and their own imaginations in a way that seems peculiarly intense compared to modern childhoods, with the ready distractions of the wider world. Moreover, they never quite managed to cast off the bonds of their family: the tentacles of the past spread into every part of their adult lives. Their influence on each other as children was potent and undiluted and it both held them back and spurred them on. For this reason I have dwelt at some length on their shared early life at Cannon Hall in London’s Hampstead.

In this, the last generation to be named du Maurier, as daughter after daughter was born, it was hoped that at least one of them would have been a son, to ensure the continuation of the family genius and name. As mere girls, however, they would have to do as best they could. It was good indeed, but could it ever be good enough? The superlatives that surrounded their parents and forebears entered the romance of their family inheritance. ‘These things added to our arrogance as children,’ was how Daphne described the effect in her scintillating recreation of a theatrical childhood in her novel The Parasites: ‘as babies we heard the thunder of applause. We went about, from country to country, like little pages in the train of royalty; flattery hummed about us in the air, before us and within us was the continual excitement of success.’

Edwardian parental influence and du Maurier expectation was paramount. But given the distinctiveness of their upbringing, the sisters relied on each other for education and entertainment, with little change of view contributed by outside friends or adults who were not in the theatre. This hot house amplified their importance in each other’s lives; family dynamics are seldom more complex and long-lived than in the love and rivalry of sisters.

‘You have the children, the fame by rights belongs to me,’

Virginia Woolf famously wrote to her elder sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, expressing an age-old sense of natural sisterly justice. But this fragile balancing act was overthrown in the du Maurier family. For as it transpired, Daphne, the middle sister, not only had the fame but also the children, the beauty, the money, the dashing war-hero husband; she won all life’s prizes, her fame so bright that it eclipsed, in the eyes of the world, her two sisters and their creative efforts as writer and painter. However, Daphne did not value these prizes. Nothing mattered as much to her as the flight of her extraordinary imagination that animated some of the most haunting stories of the twentieth century.

Her elder sister Angela, more extrovert and expressive, had the emotional energy for children and wrote of her longing to have been a mother. Certainly fame too promised to bring her more pleasure than it ever did to Daphne, who recoiled from publicity and the importuning of fans. Angela, eclipsed as she was, nevertheless came so close to claiming a share of the limelight; when she turned to singing she did not even get to first base as an opera singer, although her love of opera was to last a lifetime and she tried yet failed to join her parents’ profession and become an actor. Insecure and easily discouraged, she quickly abandoned her youthful dreams of a life of performance as enjoyed by her parents. Instead, her emotional nature found an outlet in fiction, a highly regarded aspect of the family business thanks to the success of their grandfather the artist George du Maurier, whose late career as a novelist brought him transatlantic fame.

Soon after the publication in 1928 of Radclyffe Hall’s notorious novel, The Well of Loneliness, a plea for understanding ‘sexual inversion’ in women, Angela began writing her own first novel, The Little Less. Given the damning prejudices of the time, together with her father’s powerful influence and horror of homosexuality, Angela showed surprising courage – even revolutionary zeal – in exploring the bold theme of a woman’s love for another. Like The Well of Loneliness, Angela’s novel was not a great literary work, but it was a brave one and would have brought her a great deal of notice and some riches. Publication and attention would have established her as a novelist to watch and encouraged her to continue, and grow. Instead, she was met by rejection from publishers scared of another scandal. Her tentative flame of independence was snuffed out and she was left demoralised, perhaps even ashamed, for she had thrown light on a taboo subject and been silenced. She put the manuscript away, returned to the distraction of a busy social life and did not write again for almost a decade.

Meanwhile, Daphne had been writing a few startling short stories since she was a girl and then, sometime later in 1929, had begun her first novel. The Loving Spirit, a rather more conventional adventure story, was spiced with what was to become the characteristic du Maurier sense of menace. This too was not a particularly good book but it was a much safer subject and easily found a publisher in 1931. Daphne was launched as a writer on a spectacular career that powered her through four books in five years to the darkly atmospheric Jamaica Inn and then, two years later in 1938, her creative prodigy Rebecca stormed to bestseller status. The momentum was now entirely with her. Daphne’s writing career, financial security and reputation were all made by the phenomenal success of Rebecca, and the haunting Hitchcock film that followed. The eclipse of her sisters was complete.

Jeanne, seven years younger than Angela, had also made a bold move that went against the powerful family ethos. She had tried her hand at music and was a fine pianist all her life, but her real love was painting. Hers was a family brought up to decry anything modern in the arts. The French Impressionists, the English Post-Impressionists, whose exhibition in London in 1910 had caused uproar among polite society, all horrified their father Gerald du Maurier. He was vocal in his derision of any art after the mid-nineteenth century and his opinions were held in Mosaic regard by his adoring family. ‘Daddy loathed practically everything that was modern. He hated modern music, modern painting, modern architecture and the modern way of living … Gauguin horrified him I do remember,’ Angela wrote, adding, ‘I’m not at all sure it’s a good thing to be as impressed by one’s parents’ ideas and opinions as I was by Daddy’s.’

Angela was not alone. All the sisters were in awe of their father’s opinion on most things and Angela and Daphne never came to appreciate twentieth-century art. This made it all the more remarkable, but also painful for her, that Jeanne made her career as a painter, not of conventional, narrative, realistic pictures that her family might have appreciated, but of quiet, contemplative, modernist works. Her family did not value her art enough to hang it with pleasure on their walls, although her paintings were considered good enough by the art establishment to be bought by at least one public gallery. Jeanne seemed not to long for children, neither did she court fame, but her painting was the mainspring of her life and her immediate family’s lack of appreciation of her work was a kind of denial too.

The intriguing threads of inheritance, character, family mythology and circumstance combine with early experience to create the pattern of a life. It is in childhood that these elements make their deepest impression. Here can be found possible reasons for Angela’s lack of perseverance that became a lasting regret: ‘I have always been an easily discouraged person … I had not the “guts” to start again writing’.

Inheritance and familial experiences gave Daphne the contrary commitment; imagination and writing were the things most worthwhile in life. It helped that her talent was encouraged by her doting Daddy who saw so much in his favourite tomboy daughter to remind him of his own father. ‘[He] told me how he had always hoped that one day I should write, not poems, necessarily, but novels … “You remind me so of Papa,” he said. “Always have done. Same forehead, same eyes. If only you had known him.”’

In childhood Jeanne found the seeds of her later independence. Her mother’s favourite and perhaps the most honest and down-to-earth of them all, she was the youngest sister who chose a discredited style of painting as her life’s work and managed to live openly until her death with a woman poet as her partner, despite the oft-expressed antipathy of her father towards people like her.

The sense the family had of being glamorous, exceptional and blessed with French blood was reinforced by the private language they shared. This was a highly visual and entertaining creation that bound them together as a tribe and kept out pretenders. Daphne’s fascination with the Brontës and Gondal, their imaginary world, brought the verb ‘to Gondal’ into the sisters’ lexicon, meaning to make-believe or elaborate upon. Nicknames too were a du Maurier habit. Angela became various forms of ‘Puff’, ‘Piff’ and ‘Piffy’; Daphne was ‘Tray’, ‘Track’ or ‘Bing’; and Jeanne was ‘Queenie’ or ‘Bird’.

Exploring Daphne’s character and work in the context of her sisters, means she appears in a quite different light from the one that shines on her as the solitary subject of a life. She was shyly awkward and intransigent, a girl who escaped into her own imaginary world, where she was supreme. Intent on wresting control over her destiny she thereby influenced the lives of others, not least her sisters’.

In introducing her two much less famous sisters, I hope this book draws them from the shadows. I like to think that Angela, who longed for more notice during her lifetime and dreamed of having a film made from at least one of her stories (Daphne had ten – the unforgettable Rebecca, The Birds and Don’t Look Now among them), would have been delighted to be rediscovered, her books read, possibly even inspiring a belated dramatisation. Where Daphne controlled her universe, Angela, at the mercy of her emotions, seemed to be buffeted by hers. Unfocused when young, and wilting under pressure, her youth was marked by humiliations and missed opportunities, while she was intent on the pursuit of love. Later she discovered a remarkable courage to tackle in her novels and her life injustice in matters of the heart, and to live as unconventionally as she pleased. As she aged, however, the constraining bonds of her Edwardian upbringing tightened around her once more.

A little light shed on Jeanne might also lead to a wider audience for her art, with paintings taken out of storage in small galleries and hung on the walls, for new generations to appreciate. The largest public collection is at the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol, where the quiet atmospheric beauty of her works rewards the eye with a spare, unsentimental vision. She was perhaps the most solid and least flighty of them all. Jeanne was always the honest, boy-like sister and did not apparently struggle with questions of identity or her role in life. When she decided what she wanted to do, all her energy was committed to it, unlikely to be deflected by emotion or propriety.

Much has been written on every aspect of Daphne du Maurier’s work and life. Margaret Forster’s impressive biography published nearly twenty years ago remains the authority on her life, but there are other essential contributions from Judith Cook’s Daphne: A Portrait of Daphne du Maurier and Oriel Malet’s Letters from Menabilly. Her daughter Flavia Leng’s poignant memoir adds another layer of understanding. Daphne’s writing attracted penetrating analysis in Avril Horner and Sue Zlosnik’s Daphne du Maurier: Writing, Identity and the Gothic Imagination, and in Nina Auerbach’s personal take on the themes of Daphne’s fiction in Daphne du Maurier, Haunted Heiress. The rewarding mix of The Daphne du Maurier Companion, edited by Helen Taylor, and Ella Westland’s Reading Daphne, add their own layers of meaning. There is also a highly successful yearly literary festival at Fowey, established to honour Daphne’s close connection and imaginative contribution to that part of south-east Cornwall.

In this book I do not set out to write a full biography of each sister; nor have I the space to analyse their individual works in any depth, although I have discussed them when they offer extra biographical or psychological insights to the story. I have considered the du Maurier sisters side by side, as they lived in life. This adds a new perspective to the characters of each, as they evolve through the tensions and connections of ideas and feelings that flow within any close relationship. Most marked is how much the opinions and experiences of one sister find their way into the work of another. In their fiction particularly, Angela and Daphne each used aspects of their sisters’ lives to animate her own work. But all the du Maurier sisters drew on their unique childhood, a past that was always present, bringing light and dark to their lives and work.

1

The Curtain Rises

Coats off, the music stops, the lights lower, there is a hush. Then up goes the curtain; the play has begun. That is why I’m going to begin this story ‘Once upon a time …’

ANGELA DU MAURIER, First Nights

TO BE BORN a du Maurier was to be born with a silver tongue and to become part of a family of storytellers. To be born the last of the du Mauriers, as the three sisters would be, was to be born in a theatre with the sound of applause, the smell of greasepaint, and the heart attuned to drama, tension and a quickening of the pulse. The du Mauriers were in thrall to myths of their ancestors. Even the romantic name that meant so much to them was an embellishment on something more mundane. As soon as they were old enough to understand, Angela, Daphne and Jeanne du Maurier realised they were special and had inherited a precious thread of creative genius that connected them to their celebrated forebears.

Although Daphne did marry, all three sisters evaded the conventional roles of wife and mother and rose instead to the challenge of living up to their name, a name they never relinquished. Two sisters expressed themselves through writing and the third through paint. The du Maurier character was volatile and charming, inflated with fantasy and pretence; characteristically they hung their lives on a dream and found little solace in real life once the romance had gone.

These three girls inherited a name famous on both sides of the Atlantic: their grandfather George du Maurier was a celebrated illustrator, Punch cartoonist and bestselling novelist. His most famous creation was Trilby and this sensational novel enhanced his fame and made him rich: it gave the world the ‘trilby’ hat and made his anti-hero, the mesmerist Svengali, part of the English language as a byword for a sinister, controlling presence. It was his first novel, Peter Ibbetson, however, that impressed his granddaughters most, insinuating into their own lives and imagination its haunting theme that by ‘dreaming true’ one could realise the thing one most desired. The sisters attempted in their different ways to practise this art in life and incorporate the idea in aspects of their work.

George’s grandfather, Robert, had expressed his love for fantasy by inventing aristocratic connections for his descendants and adding ‘du Maurier’ to the humble family name of Busson. His own mother Ellen, great-grandmother to the sisters, was filled also with the sense she was not a duckling but a swan. As the daughter of the sharp-witted adventuress Mary Anne Clarke, she was brought up with the tantalising thought that her father might not be the undistinguished Mr Clarke, but the Duke of York, the fat spoiled son of George III. Such stories, lovingly polished through generations, contributed to the family’s sense of pride and place. Only Ellen’s great-granddaughter Daphne, with her cold detached eye, was not seduced. She recognised the destructive power of this pretension: ‘She will wander through life believing she has royal blood in her veins, and it will poison her existence. The germ will linger until the third or fourth generation. Pride is the besetting sin of mankind!’

Yet the du Maurier story ensnared her too.

The family myths centred on these three tellers of tall tales: Mary Anne, Robert and the sisters’ grandfather George du Maurier. If imagination and creativity ran like a silver thread through the du Mauriers, so did emotional volatility and lurking depression. In some this darkened into madness, with George’s uncle confined to an asylum and his father so subject to bi-polar delusions (he believed he could build a machine to take his family to the moon) that he lived a life of impossible ambition and frustrated dreams. Some of these soaring flights of fancy would find alternative modes of expression in subsequent generations.

George’s elder son, Guy, like George himself with Trilby, was overtaken in 1909 by an extraordinary flaring fame with An Englishman’s Home, a patriotic play he casually wrote before going to serve as a soldier in Africa. This was five years before the start of the Great War and he satirised his country’s unpreparedness. Sudden international celebrity was followed too soon by Guy’s heroic death in the world war he had foretold. George’s youngest child, Gerald, became an actor whose naturalistic lightness of touch changed the face of acting, where life and art seemed to combine in an effortless brilliance. Gerald made memorable the character of Raffles, the gentleman thief, and was the first actor to play J. M. Barrie’s Mr Darling and Captain Hook in Peter Pan. His portrayal of this unpredictable cavalier pirate set the template for that character’s appearance and behaviour in subsequent productions. This was the father of the du Maurier sisters, Angela, Daphne and Jeanne.

As with all sisters, the du Mauriers’ relationship with each other was an indissoluble link to their childhood: for them that meant above all a link with their father and with Peter Pan. The play’s creator, J. M. Barrie – Uncle Jim to the girls – was a prolific and successful Scottish author and playwright who, nearly a generation older than their father, had been influential in Gerald’s early career and become a friend. Ever since they could first walk, the girls were taken on the annual pilgrimage to see the play performed at their father’s theatre, Wyndham’s. There, as the pampered children of the proprietor, they sat dressed in Edwardian satin and lace in their special box, saluted by the theatre staff and stars. They were celebrity children.

Throughout their childhood the sisters would re-enact the play in their nursery, the words and ideas becoming engraved deep into their psyches. Daphne was always Peter; Angela was more than happy to play Wendy, while Jeanne filled in with whatever part Daphne assigned her. Peter Pan excited their imaginations and intruded on every aspect of their lives. Their father was closely identified with the double personae of Mr Darling and Captain Hook, and Peter himself, brought to life the same year Angela was born, remained the seductive ageless boy. While the du Maurier sisters reluctantly accepted that they had to grow up, Peter Pan lived on in an unchanging loop of militant childishness, mockingly reminding them of what they had lost. The excitement and wonder of the theatre, however, was something they never lost. It informed their lives, finding expression in their work, in the dramatic character of their houses and their attraction to those with a touch of stardust in their blood.

Angela claimed Peter Pan as the biggest influence in her childhood: she saw it first performed when she was two and then finally played the role of Wendy in the theatre when she was nineteen. Her steadfast belief in fairies and prolonged childhood was encouraged by the play’s compelling messages. But the influence on Daphne was profound, for her own imagination and longings so nearly matched the ethos of the story: the thrill of fantasy worlds without parents; the recoil from growing into adulthood and the fear of loss of the imaginative power of the child. The tragic spirit of the Eternal Boy plucked at the du Mauriers, just as he did the Darling children who left him to enter the real world stripped of magic. The place between waking and dreaming would be very real to Daphne all her life and her phenomenally fertile imagination propelled her into her own Neverland, whose inhabitants were completely under her control.

Neverland was never far away. Daphne still referred to Peter Pan as a metaphor when she was old, considering her children’s empty beds and imagining the Darling children having flown to adventures that she could not share. Her powerful identification with this world of make-believe fuelled her spectacular fame and riches and an intense life of the mind, but held her back in her growth to full maturity as a woman. Her sisters, excited by the same theatricality in their childhoods, responded very differently. Angela, never quite taking flight, was shadowed by her sense of earthbound failure, yet she had the courage to grow up and risk her heart in surprising ways. Jeanne largely cast it off to go her independent way and turned to the down-to-earth pleasures of gardening, and the sensuous realities of paint. These evocative childhood experiences brought the sisters not only the comfort of familiarity – ‘routes’ in du Maurier code – but nostalgia too for the past they had so variously shared. Just a word could transport them back to the thrill of the darkened theatre of their youth, full of anticipation of the big adventure about to begin. ‘On these magic shores [of Neverland] children at play are for ever beaching their coracles. We too have been there; we can still hear the sound of the surf, though we shall land no more.’

These du Maurier girls were born as Edwardians in the brilliant shaft of light between the death in 1901 of the old Queen Victoria and the beginning of the First World War. It was a time when new ways of being seemed possible: pent-up feelings erupted into exuberant hope in the dawn of the twentieth century. Under a new and jovial king, the longing for pleasure and freedom replaced Victorian propriety and constraint, and this energy infected the nation. Such optimism extended to a young theatrical couple who married in 1903. Gerald du Maurier, as an actor and then theatrical manager, was already on a trajectory that would bring him fame, riches and a knighthood. His wife was the young actress Muriel Beaumont, cast with him in a comic play, The Admirable Crichton, a great hit in the West End. She was very young when responsibility and care for him was passed ceremonially to her from his mother (for whom he would remain always her precious pet ‘ewe lamb’) together with a list of his likes and dislikes. Muriel was a pretty actress who eventually gave up her career to be the wife of a great man and the mother of his children. Her two elder children would recall her impatience and irritability when they were young, her lack of humour, and her beauty, always her beauty.

On cue, just over a year after their marriage, on 1 March 1904 a plump baby girl was born in No. 5 Chester Place, a terraced Regency house close to London’s Regent’s Park. While Muriel laboured in childbirth with their first child, Gerald managed to upstage her. Suffering a serious bout of diphtheria, a potentially fatal respiratory disease, for which the cat was blamed, he lay in isolation on the floor above and, it seemed, at death’s door.

When Gerald had recovered and could at last see his firstborn he was delighted to have a daughter. Girls were a rarity in this generation of du Mauriers. His sister Trixie had three boys, Sylvia five, and his brother Guy and wife Gwen were childless. Most importantly, his adored father George du Maurier had longed for at least one granddaughter. ‘That endless tale of boys was a great disappointment. If only he was here to see Angela.’

For Angela is what this jolly baby was called.

In the du Maurier family it was not enough to be a girl, however rare. Aside from ancestor worship, this was a family who adored beauty, demanded beauty, particularly in its women. This aesthetic sensibility was very marked in George whose drawings of gorgeous Victorian wasp-waisted females graced his witty cartoons. Despite his father’s good looks, Gerald’s attractiveness owed more to his charm and animation than the rather ungainly proportions of his face. He may have thought himself lacking in romantic good looks, but he was lightly built and elegantly made and expected grace and beauty in others, especially his womenfolk.

Gerald’s wife Muriel was exceptionally attractive and stylish all her life, but their first daughter, by her own admission, was not: ‘I was a plain little girl, and I got plainer. Luckily, when I was small I was, apparently, amusing, but no one could deny I was plain.’

Muriel was still pursuing her acting career and baby Angela was handed over to ‘Nanny’ when she was eight months old, heralding Angela’s first great love affair in a life in which there would be many. This kind, inventive, affectionate young woman was the central loving presence in Angela’s universe and when she was dismissed, as surplus to requirements eight years later, the little girl’s bewilderment, grief and loneliness seemed to her ‘like a child’s first meeting with Death’.

Angela’s earliest memories, before her sisters joined her in the nursery, were fragments of life. Between the ages of two and three she could remember her canary dying and being replaced, seamlessly, by another. This sleight of hand was enacted a few times more during her childhood. She remembered dancing as her mother played on the piano the hymn, Do No Sinful Action, and being sharply reprimanded for this serious but inexplicable sin. But her very first memory was of wetting her pants in Regent’s Park when dressed in her Sunday best of bright pink overcoat with matching poke bonnet, trimmed with beaver fur. To complete the vision of prosperous Edwardian childhood, white suede boots clothed small feet that were not expected to stamp in puddles or run in wet grass. This memory of her immaculate outward appearance, contrasting with the shameful evidence under her coat, remained with her for life.

When Angela was three the family moved to 24 Cumberland Terrace, a larger house in a grander terrace a few hundred yards away, just as close to Regent’s Park. Muriel was expecting another baby and this time it was hoped she would produce the son and heir. Gerald’s obsession with his father made him long for a boy who might embody some of the lost qualities of artistry, imagination and charm that so distinguished George du Maurier: he wanted continuance of the du Maurier name and his father’s genius somehow reincarnated in a son.

The baby was born late in the afternoon of 13 May 1907. After a week of heat the weather had finally broken and rain pelted down from a thunderous sky, and into the world came not the expected son but another daughter, although this time she was pretty, which was some consolation. Angela did not remember her sister’s arrival but she recalled her mother insisting ‘she was the loveliest tiny baby she has ever seen’.

Gerald was playing that night to packed houses in a light comedy called Brewster’s Millions. The eponymous hero, who had to run through a million-dollar legacy before he could inherit another seven million, mirrored something of Gerald’s own cavalier attitude to money: his characteristic off-hand style and sense of fun endeared him to the audience. He returned from the theatre to find Nanny in charge of this second daughter.

Gerald decided to call her Daphne, after the mesmerising actress Ethel Barrymore, who had much preferred the name Daphne to her own, and had jilted him before he had met Muriel. One wonders if Muriel knew after whom her second daughter was named – perhaps thinking the impetus was the nymph Daphne who ran from Apollo and his erotic intentions (as a last resort transforming herself into a laurel tree), rather than the American beauty from a great acting dynasty who ran from Gerald and his ravenous need for uncritical adoration.

Daphne fitted into a nursery routine long practised by Nanny and Angela. Angela was almost four and for nearly all that time had been the focus of Nanny’s love. She may not have remembered her sister’s birth but recalled she had to relinquish sole command of the nursery and share her beloved with a demanding interloper. Apart from a couple of terms, Angela did not go to school and was not able to establish a new kingdom for herself outside the confines of the nursery. Life continued in its soothing routines but now everything had fundamentally changed.