По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

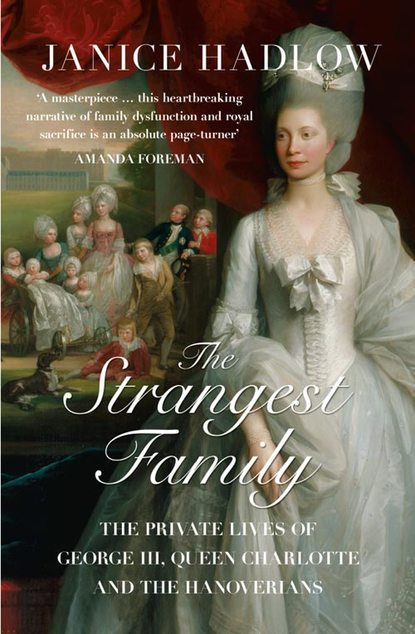

The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Other British entrepreneurs undertook a darker business. Slavery was ‘one of the staple trades of Englishmen’, and the great ports of Bristol and Liverpool were largely built on its tainted dividends.13 (#litres_trial_promo) The huge returns generated by such ventures, whether trading in people or in things, ramped up confidence, creating a perfect storm of enthusiasm for the very idea of commerce itself. ‘There never was,’ observed Samuel Johnson, ‘from earliest ages, a time in which trade so much engaged the attention of mankind, or commercial gain was sought after with such general emulation.’14 (#litres_trial_promo) In Britain this was experienced with particular intensity; the nation’s sense of itself as a great trading nation was, in the mid-eighteenth century, firmly and irrevocably embedded in its identity as a free and enterprising people. Part of the appeal was a simple one: trade made a great number of investors a great deal of money, but it played a role in the construction of an idea of Britishness that went far beyond the advantage of individual profit. The fruits of commercial enterprise were widely believed to underwrite all the constitutional advantages which made Britain so specially favoured among nations. The private wealth it generated, which could not be taken away by taxation unless approved by Parliament, acted as a bulwark against the ambitions of despotic power at home. A poor and hungry people was not a free people, and was easily corrupted by the bribes or threats of overmighty rulers. The profits of trade paid for a strong navy, which kept the seas safe for British exports abroad, but, unlike a standing army, could never be used to threaten the integrity of domestic politics. It delivered a prosperity which, as early economists already understood, kept the wheels and ploughs of industry turning. There was no aspect of the distinctive British way of life which it did not touch. It was little wonder that at every convivial supper or political gathering of the period, once a toast had been drunk to the king, it was the invocation ‘To trade’s increase!’ that was greeted with the most heartfelt and passionate sense of shared feeling.

The wealth produced from the profits of trade was to be seen in all the great commercial centres of Britain – Liverpool, Bristol and Glasgow – which expanded rapidly in the 1760s and beyond. The influence of new money was also evident in the development of pleasure resorts such as Bath and Cheltenham, towns which existed largely as a way to spend profits made elsewhere. Then as now, it was through property – the building, designing and furnishing of houses – that individual prosperity found its most visible expression. These were the years in which the urban centres of Britain were rebuilt and re-imagined as the rich, the genteel and the polite moved surely and steadily out of the old city quarters, leaving behind their uncomfortable proximity with dirty trades and the insolent poor, constructing for themselves new houses built in terraces and squares, on clean, classical lines, punctuated by parks and gardens. Across the monied hotspots of Britain, the process was endlessly and elegantly replicated, from Edinburgh to Dublin to Newcastle, creating a vision of town life whose ordered, light and spacious appeal endures to this day.

The changes to the landscape of mid-eighteenth-century life were not confined to the cities. There was as yet little obvious sign of the revolution in industrial production that would transform Britain out of all recognition during George III’s long reign. In the valleys of Coalbrookdale and the iron foundries of Wales, in the workshops of the Midlands and the mills of Lancashire, new technologies were being developed – engines, looms and furnaces – which would recast the relationship between humanity and the natural world, ushering in production on a hitherto unimaginable scale; but it would be at least another twenty years before these became the dominant and visible signature of British economic expansion.

But for most contemporaries, it was the farm, not the factory, which, after trade, was seen as the most forceful engine of change. For over a generation, it had been improvements in agriculture which had underpinned prosperity. The green, rural countryside that forms such an elegiac backdrop to so much Georgian art was in fact one of the most intensively managed landscapes in Europe. The application of scientific methods to farming – especially new fertilisation techniques which overcame the need to let fields lie fallow for years at a time – transformed crop yields and increased profits, providing a tempting incentive to consolidate smaller holdings into larger and more efficient businesses. For some, the result of these changes was impoverishment: families who had once owned small plots of land were forced off them and into the day labour market, subject to the fluctuating needs of the season and the whims of the farmer’s overseer. For others, the result was cheaper food and much more of it. This left them with more disposable income to spend; for perhaps the first time in history, significant numbers of ordinary people had money to buy goods beyond the basic necessities of life. Their purchases in turn put more money into the hands of those who made the things they bought, and the outcome was a steady but significant increase in both the wealth and buying power of ‘the poor and middling sorts’.

This steady diffusion of prosperity was obvious to anyone visiting Britain. Every observer noted that there was clearly a good deal of new money around. Among the very rich, it was apparent in the construction of great new country houses, and in the seemingly limitless demand for luxurious objects to put in them: clocks and carpets, portraits and brocades, china and silverware, chairs, tables and sideboards. What struck foreign visitors most powerfully, however, was the degree to which the middle classes, and even some of the poor, shared in the general sense of improved wellbeing. In the opinion of one German writer in the 1770s, the ‘luxury’ enjoyed by the middle and lower classes ‘had risen to such a pitch as never before seen in the world’.15 (#litres_trial_promo) A few years later, a Russian traveller compared the general wellbeing he saw in London with the gulf between rich and poor he had witnessed in France. ‘How different this is from Paris! There vastness and filth, here simplicity and astonishing cleanliness; there wealth and poverty in continual contrast, here a general air of sufficiency; there palaces out of which crawls poverty, here tiny brick cottages with an air of dignity and tranquillity, lord and artisan almost indistinguishable in their immaculate dress.’16 (#litres_trial_promo)

As he went on to remind his readers, squalor and poverty were of course still to be found in eighteenth-century England, but most foreign observers agreed that a larger proportion of the British now seemed to have escaped the worst deprivations that were the general experience of the European poor. Back in the 1720s, de Saussure had observed with surprise that ‘the lower classes are usually well dressed, wearing good cloth and linen. You never see wooden shoes in England, and the poorest individuals never go with naked feet.’17 (#litres_trial_promo) Indeed, in England, the wearing of ‘wooden shoes’ was indelibly associated with the desperate poverty held to be the inevitable product of life under Catholic absolute monarchies. The passionate cry of: ‘No popery and no wooden shoes!’, which so often resounded through the streets of eighteenth-century London, was an expression of the conviction held by even the poorest Britons that they enjoyed a standard of living of which their foreign counterparts could only dream.

The small prosperity of small people created the demand for ever larger numbers of affordable goods. British manufacturers soon showed themselves eager and adaptable enough to supply them. Unlike many of its grander European competitors, the British market did not just cater to the super-rich – to ‘the magnificence of princes’. It was just as interested in selling to new customers, less wealthy but more numerous. Matthew Boulton, the great Birmingham-based producer of the buckles and buttons that were an essential part of every eighteenth-century wardrobe, had no doubt which of the two kinds of buyer he valued most. ‘We think it of far more consequence to supply the People than the Nobility only … We think that they will do more towards supporting a great Manufactory than all the Lords of The Nation.’18 (#litres_trial_promo) Boulton understood that an entire new market had emerged, a new generation of purchasers, looking to achieve their own moderately priced vision of the good life, and he and others were ready and willing to supply it. ‘Thus it is,’ wrote the clergyman and economist Josiah Tucker, ‘that the English … have better conveniences in their houses and affect to have far more in quantity of clean, neat furniture and a greater variety, such as carpets, screens, window curtains, chamber bells, polished brass locks, fenders etc., (things hardly known abroad amongst persons of such rank) than are to be found in any country in Europe.’19 (#litres_trial_promo) These simple and often extraordinarily resilient objects, designed to appeal to the taste of modest eighteenth-century buyers, were made in such numbers that any frequenter of modern auction rooms or antique shops will be familiar with them. Those that have survived the uses and abuses of 250 years are often beautiful to look at and still desirable things to own. They are also mute witness to the power of a quiet revolution which began to transform British experience just as George III began his reign. He was the first king to rule over a nation of consumers.

The Britain in which the young king acceded in 1760 was an assertive and forceful society, sometimes brash and overbearing in the robustness of its self-belief. It was not an easy place in which to be poor, vulnerable, sensitive or a failure; but for those who could stand the pace, and who were not among the losers crushed by the relentlessness of its forward movement, the experience of being British in the mid-eighteenth century was dominated by a sense of energetic exhilaration, an acute consciousness of an upward trajectory towards levels of international power and domestic wealth that were unthinkable only a generation before. The experience of the nation thus mirrored that of its inhabitants; both now found themselves in possession of assets that had arrived with swift and surprising speed. Horace Walpole caught the mood perfectly. ‘You would not know your country again,’ he wrote to a friend who had long lived abroad. ‘You left it as a private island living upon its means. You would find it now capital of the world.’20 (#litres_trial_promo)

*

In such circumstances, the accession of a youthful king, whose vitality seemed to reflect the ambition of the country he ruled, was greeted with unconstrained enthusiasm. George II had been on the throne since 1727. He was an old man, aged seventy-six at the time of his death, who belonged to the old world. Of the new monarch, Philip, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, usually the most detached and cynical of observers, wrote that he was the king of ‘his united and unanimous people, and enjoys their confidence and love to such a degree that were I not as fully convinced as I am of His Majesty’s heart and the moderation of his will, I should tremble for the liberties of my country’.21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Impressions of the young man at the centre of this whirlwind of attention were universally positive, contrasting his affability with the curmudgeonly attitudes of his elderly predecessor. Walpole, who rushed to court to get an early look at his new ruler, was pleased with what he found: ‘This sovereign don’t stand in one spot, with his eyes fixed royally on the ground and dropping bits of German news; he walks about and speaks to everybody.’22 (#litres_trial_promo)

The polite and considerate monarch had not yet grown into the bulky figure he would become in early middle age, the familiar image of florid imperturbability whose prominent blue eyes gaze so resolutely from later portraits. Although he was not conventionally handsome, the Duchess of Northumberland, who knew him well, described him tactfully as ‘tall and robust, more graceful than genteel’. The family tendency towards fat, against which George struggled diligently throughout his life, meant that he would never look the part of either romantic hero or fashion plate. He had strong, white teeth, evidently enough of a rarity, even in aristocratic circles, to merit approving comment by a number of observers. His hair, when neither powdered nor hidden beneath a wig, was considered one of his best points. It was, the duchess recorded, ‘a light auburn, which grew very handsomely to his face’. She also admired his clear and healthy complexion, but noted that in common with others of his age, ‘he had now and then a few pimples out’. For the duchess, however, it was George’s demeanour that mattered more. ‘There was a noble openness in his countenance, blended with a cheerful good-natured affability,’ which trumped his prosaic appearance and even gave him a certain fugitive charm.23 (#litres_trial_promo) The portrait that best captures the elusive quality of George’s appeal was made a few years before his accession by the Swiss painter Jean-Etienne Liotard. Delicately rendered in pastels, it does not flatter – the man George would later become is visible in the round lineaments of his face, the fullness of his mouth and the protuberance of his eyes – but it captures brilliantly the clear-eyed, healthy, pink-and-white freshness of his youthful self.

George’s looks were only part of the story. In the opening weeks of his reign, admiration for the new king’s ‘open and honest countenance’ was exceeded only by approval of the unstudied excellence of his behaviour. Everyone who saw him in the immediate aftermath of his grandfather’s death commented on the considerate correctness of all his actions. ‘He has behaved with the greatest propriety, dignity and decency,’ observed Walpole.24 (#litres_trial_promo) He knew how to carry himself respectfully at solemn moments, but onlookers were also struck by his ability to strike a lighter note. His unforced, natural warmth of character was particularly admired. Lady Susan Fox-Strangways, who saw him often at court, approvingly observed in him ‘a look of happiness and good humour that pleases everyone – and me in particular’.25 (#litres_trial_promo)

The grace and cheerfulness that George displayed in these days of excitement and promise were more than the temporary product of a moment; he was an essentially good-hearted man, who tried to observe the decencies of gentlemanly behaviour even in the darkest and most trying times of his reign. However, the polite, easy candour celebrated by so many observers in those early days was only part of who he really was. There was a sombre, more thoughtful cast to his character, which Liotard’s portrait caught as acutely as it did the new-minted freshness of his features. The young George stares watchfully out from the canvas, with an air of wary self-containment. This is a serious man, with a serious purpose in mind – there is no hint of frivolity or light-heartedness in his measured expression. For all its tenderness, it is also an image of quiet, sustained – even steely – determination; and it was a better indicator of what lay in George’s mind as he contemplated the future than all the benign gestures with which he navigated the immediate aftermath of his grandfather’s death. For George III came to the throne determined to do more than merely replace George II. He aspired to be not just the next king, but a new kind of king.

As heir to the crown, George had spent much of his youth transfixed by the inevitability of his destiny, trying to comprehend what was expected of him. What was the true purpose of kingship in the modern world? Why had he been called upon to undertake this extraordinary and unasked-for burden? How could he discharge it as providence intended, fulfilling his duty to God, to himself and to his subjects? The answers to these questions, he eventually concluded, encompassed far more than the narrowly political concerns that had absorbed the energies of his predecessors. Their obsession with the day-to-day management of political business, the ups and downs and ins and outs of ministerial fortunes, had obscured the unique and singular meaning of sovereignty. The job of a king, George had decided, was no less than to graft moral purpose on to the nation’s polity. It was his role to act as the conscience of the country, and the guardian of its true interests. He was, George believed, the active agent of principle in public life, a figure intimately connected with the daily workings of politics and yet with a significance far beyond them. It was his duty to remind politicians what the point of politics was and, through his interventions and understanding, to direct them beyond their personal and party interests towards a larger and more lasting common good.

This interpretation of his task did more than influence George’s public life; it also profoundly shaped his sense of his duties as a private man. How could a king act as a moral compass to others if he did not live a moral life himself? George’s idea of kingship thus reached far beyond a purely public dimension; it contained within itself a powerful personal imperative too. There was a direct connection between his actions in the political world and his conduct at home. He could not act as a force for good in the national interest if he was unable to live by right principles in his private life.

George’s desire to see these ideas reflected in his actions as king was to put a great deal of pressure on the established order of politics in the years immediately after his accession; but it was their impact on the intimate world of the royal family that would prove far more revolutionary and of much greater lasting significance. He knew that to deliver the moral authority he needed to justify his vision, he would need to create a new kind of family life for himself. This meant redefining the personal relationships at its heart, reshaping what it meant to be a royal husband, wife, son or daughter. This would involve a greater emphasis on meeting high moral standards, a greater stress on duty, obligation and conscience. But he would also attempt to introduce into these roles something of the human warmth and emotional authenticity he believed non-royals found in them, hoping to provide for his wife and his children the solace and affection that seemed so singularly lacking in the lives of his immediate predecessors.

Because in becoming a new kind of king, George recognised that he would also have to become a new kind of Hanoverian. He understood that his idea of kingship required him to turn his back on his family’s past, rejecting a malign inheritance of emotional dysfunction that had been handed down from generation to generation. Both his great-grandfather, George I, and grandfather, George II, had hated their sons with a passion bordering on madness. None of his male relations had been faithful to his wife. Every Hanoverian prince kept a succession of mistresses with scant concern for the feelings of his spouse, who responded with either mute resignation or loud and furious cries of dismay. The children of these unhappy unions were, unsurprisingly, rarely happy themselves. Drawn into feuds between their parents, they were angry, jealous and disaffected. They schemed and quarrelled between themselves and seemed destined to repeat the behaviour that had destroyed any chance of contentment for their parents. As George saw it, this legacy of amoral, cynical behaviour had warped and corrupted the Hanoverians, crippling their effectiveness as rulers and making their private lives miserable. It had made them bad kings and bad people. It had set husband against wife, father against son, sister against brother. It had thwarted their ambitions and corrupted their affections, leaving in its wake nothing but bitterness.

George planned to put an end to the whole painful cycle. On the very day he became king, he sent for his uncle, William, Duke of Cumberland, the victor of Culloden, with whom he had had many differences in the past, and announced his intention to outlaw the old habits of spite and bad faith. Walpole heard that George had been most explicit in signalling the magnitude of the change, telling the duke that ‘it had not been common in their family to live well together, but that he was determined to live well with all his family’.26 (#litres_trial_promo) It was such a public declaration that everyone appreciated its significance.

George’s intention to reform the way his family related to one another underpinned all the decisions he made about his private life in the years that followed. It dictated his choice of a wife, and shaped the ambitions he had for their relationship within marriage. It influenced his attitude to fatherhood, and was the foundation upon which he based the upbringing of his small children. It governed the way the young princes and princesses were educated and laid down a pattern of behaviour they were expected to follow as adults. Alongside his profound Christian faith – another distinction that marked him out from his forebears – it informed almost every action he took in relation to his intimate, personal world.

At one level, his devotion to the project grew out of something deeper than conscious strategy; it was a manifestation of the most enduring aspects of his personality, a reflection of the qualities of exacting, dutiful conscientiousness that were indivisible from his character. George acted as he did because he was who he was. But his desire for change owed as much to his sense of history as to the promptings of his nature. He was profoundly aware of his family’s failings and believed passionately that it was his duty to reject the pattern of behaviour they had bequeathed to him. For that reason, the lives of George’s predecessors are worth exploring, in all their dissolute, chaotic extraordinariness. They were the mirror image of everything George thought valuable and true in human relationships – a dark vision of just how wrong things could go when all sense of discipline, restraint and honest affection was lost. To appreciate what motivated the most upright of the Hanoverians, it is necessary to understand something of the people against whom he so firmly defined himself.

CHAPTER 1

The Strangest Family

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

GEORGE III’S FIRST SPEECH FROM the throne was a resounding declaration of his particular fitness to take up the task before him. ‘Born and educated in this country,’ he pronounced, ‘I glory in the name of Britain.’1 (#litres_trial_promo) It was not a statement any of his immediate predecessors could have made, which was of course precisely why he said it. From the very earliest days of his reign, he sought to mark himself out from his Hanoverian forebears. Neither George I nor George II had been born in Britain, and neither ever thought of the country as home. Their true Heimat was Hanover, a princely state in northern Germany in whose flat farmlands the dynasty had its ancestral roots. They both thought of themselves first and foremost as electors of Hanover; their kingship of England, Scotland and Ireland came very much second in their hearts.

When George III became monarch, the family had been somewhat reluctantly seated on the throne for only forty-six years. The crown of Great Britain had not been a prize they had expected to inherit, but they had done so with the death of Queen Anne in 1714. Anne was the daughter of James II, the last Stuart king, who was forced off his throne in 1688 when his Catholicism became unacceptable to the Protestant English. In the Glorious Revolution that followed, the Dutch prince William of Orange, nephew and son-in-law of the deposed James, was invited to become king, with the stipulation that henceforth, only a Protestant could become sovereign, a qualification still in force today. Anne, who succeeded the childless William, was known with cruel irony as ‘the teeming Princess of Denmark’. Her pregnancies were many, but, despite an appalling catalogue of gynaecological endurance, she had no living children to show for it; she lost five babies in infancy and suffered thirteen miscarriages. When her only surviving child, the eleven-year-old Duke of Gloucester, died in 1700, it was clear that an heir must be looked for elsewhere.

The defenders of the Glorious Revolution did not find it easy to identify a suitably qualified candidate. Catholicism ruled out James II’s exiled son, who had otherwise by far the strongest claim, as well as fifty-six other religiously unacceptable potential heirs. Eventually, it was decided to offer the crown to Electress Sophia of Hanover. A daughter of Charles I’s sister Elizabeth, in purely dynastic terms her claim was weaker than those of many more directly related contenders, but her impeccable Protestant credentials won the day, and it was her name and that of her descendants which was enshrined in the Act of Settlement of 1701 as heirs to the crown if Queen Anne should die without a child. When Anne’s health, exhausted by a lifetime of fruitless childbearing, fatally gave out in 1714, the electress was already dead, so the succession passed to her eldest son, George Louis. He was crowned in London later that year as George I.

It was not an entirely popular choice. The Jacobites – supporters of the old Stuart monarchy – rioted in at least twenty English towns. It was worse in Scotland, still smarting with outraged national grievance at the Act of Union, which linked the nations together in 1707, and whose simmering discontents erupted into the uprisings of 1715 and 1745. Although on those occasions it looked as if Hanoverians might be forced back to the electorate that was always their first love, they hung on, somewhat despite themselves, and it was their dynasty that ruled Britain until the death of George III’s son, William IV, in 1837.

As a child, the diarist Horace Walpole, who wrote so voluminously about George I’s successors, had a brief encounter with the first of the Hanoverians. His father, Sir Robert Walpole, was George’s first minister, and as such was able to gratify for his son ‘the first vehement inclination that I ever expressed … to see the king’. He was taken in the evening to St James’s Palace and, after supper, informally introduced to the monarch. The ten-year-old Horace ‘knelt down and kissed his hand, he said a few words to me, and my conductress led me back to my mother’. Writing nearly seventy years later, Walpole recalled that ‘the person of the king is as perfect in my memory, as if I saw him but yesterday. It was that of an elderly man, rather pale and exactly like his pictures and coins; tall; of an aspect rather good than august; and with a dark tie wig, a plain coat, waistcoat and breeches of a snuff-coloured cloth, with stockings of the same colour, and a blue riband all over.’ He had, he thought in retrospect, been remarkably indulged, for the king ‘took me up in his arms, kissed me and chatted some time’.2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Walpole, who in later life liked to think of himself as almost a republican, and who observed that he had ‘never since felt any enthusiasm for royal persons’, was clearly captivated. But there was another side to the king who seemed so kind and genial to the starstruck small boy. For it was George I who must bear much of the responsibility for nurturing the tradition of Hanoverian family hatred that was to bequeath such a miserable inheritance to future generations.

*

George I’s own experience of family life was hardly a happy one. His father, Ernst August, was a man of calculating ambition, dominated by the all-pervasive desire to see his dukedom of Hanover elevated to the far greater status of an electorate. His many children were raised in an atmosphere of military discipline, expected to display absolute obedience to his will and utter devotion to the grand project of dynastic consolidation. He seldom saw any of them alone or in informal circumstances; unsurprisingly, they were said to be ‘solemn and restrained’ in his presence.3 (#litres_trial_promo) Ernst’s wife Sophia, whose antecedents were ultimately to bring the crown of Great Britain into the family’s possession, was a far more relaxed and sympathetic character than her unbending husband – Walpole described her as ‘a woman of parts and great vivacity’ – but she too submitted without question to her husband’s severe dictatorship.4 (#litres_trial_promo) Any resistance on her part had been undone by love. She had expected very little from her arranged marriage, and when, against all her expectations, Ernst proved a passionate and enthusiastic lover, Sophia could not believe her luck. From her wedding night onwards, for the rest of her life, she was completely in thrall to her husband’s judgement, never venturing to set her own considerable intellect against any of his schemes. Ernst’s numerous affairs with other women caused her much pain – in middle age, she wrote sadly that she could not believe she had ever been so foolish as to imagine he would remain faithful to her for ever – yet she fought hard to preserve her primacy in his eyes. She was much tried by his long relationship with the malicious Countess von Platen, who subjected her over many years to a litany of carefully calculated public insults; but Sophia’s commitment to the errant Ernst August never wavered. She once declared that she would ‘gladly have followed him to the Antipodes’.5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sophia’s dogged devotion won her no part at all in her husband’s political strategising. He acknowledged the sharpness of her mind but denied her any active role in his schemes. She was ‘without influence’ in family affairs and allowed no say in the making of even the most significant decisions. When Ernst decided to disinherit his many younger sons in order to consolidate all the family possessions in the hands of George, the eldest, Sophia could do nothing to protect their interests. Angry and betrayed, three of the brothers left Ernst’s court and signed on as soldiers in the Imperial service. Within a few years, all had died in battle, to the despairing grief of their mother. She was equally powerless when Ernst began to make marriage plans for the favoured George. Ernst had long before decided that his eldest son would marry his cousin, Sophia Dorothea of Celle, thus uniting two branches of the family dukedoms into a single greater state.

For all its desirability as a political alliance, it was obvious to anyone who knew them that George and Sophia Dorothea were hardly well matched. Sophia Dorothea, who was only eleven when the marriage was first proposed, had been brought up from her earliest days in a relaxed atmosphere of indulgence and luxury. Her father, a very different man from his single-minded brother Ernst, had married for love a woman considered beneath him in the complicated gradations of princely hierarchy, and had sacrificed the opportunity for further aggrandisement as a result. Sophia Dorothea, the only child of this love match, grew up into a beautiful woman – sophisticated, conscious of her attractiveness, and considered very French in her tastes. She loved to be amused and entertained, and was said to be obsessed by fashion. Lively and good-looking, she had no shortage of suitors. Her prospective mother-in-law regarded her balefully; she was sure she would not find a soulmate in her reserved and cautious eldest son.

Sophia, who described herself as ‘a nearly stupidly fond mother’, was devoted to the silent and watchful George.6 (#litres_trial_promo) She admired her son’s deep sense of responsibility and his formidable devotion to duty. Others found him harder to appreciate. His cousin, the Duchess of Orléans, thought him ‘ordinarily neither cheerful nor friendly, dry and crabbed’. She complained that ‘his words have to be squeezed out of him’, that he was suspicious, proud, parsimonious and had ‘no natural good-heartedness’.7 (#litres_trial_promo) Sophia maintained that those who thought her son sullen simply did not understand him; they did not see that, beneath his undemonstrative surface, he took things much to heart, and was far more sensitive than he was prepared to show. But she knew him well enough to suspect that he was not the best partner for the outgoing Sophia Dorothea, who loved playful conversation, sought out cheerful company and had a taste for extravagant entertainments. The prospective bride’s mother had similar misgivings; but neither could persuade their respective husbands to take their concerns seriously.

George himself had little to say on the subject. It was widely supposed that he would have been happy to be left alone with his mistress, a sister of the Countess von Platen, who had – as it were – continued the family business, becoming the son’s lover, as her sister was the father’s. However, obedience, not self-fulfilment, came first in the young George’s mind. He had seen Sophia Dorothea, and had apparently been impressed by her good looks; but there is little doubt that he would have taken her anyway, regardless of any personal qualities, once his father had wished it. His mother once remarked that ‘George would marry a cripple if he could serve the House of Brunswick’.8 (#litres_trial_promo) In 1682, the ill-matched couple did the bidding of their fathers, and were married. Sophia Dorothea was sixteen, her groom five years older.

At first they seem to have made the best of things, and in 1683 Sophia Dorothea gave birth to a son, George August. Such speedy provision of a healthy male heir raised her immeasurably in Ernst’s eyes, and for a few years Sophia Dorothea’s life was probably not unpleasant. Under the eye of her satisfied father-in-law, she enjoyed court life at the elaborate palace of Herrenhausen, relishing the parties, masques and concerts Ernst August laid on there to magnify his grandeur. She saw very little of her husband. George’s great passion was the army, which took him away on active service for long periods. When Ernst August took his entire court to Italy for a year, Sophia Dorothea went on the extended holiday without her husband. Reunited with George on her return, she conceived a daughter who was named after her. But thrown back into each other’s company, the strategy of polite coexistence the couple had maintained with some success began to fall apart. Bored and frustrated, Sophia Dorothea began to behave badly; she picked quarrels, caused scenes and was outspokenly impatient of the etiquette that ruled court life, apparently driven both to dominate and to despise the circumstances in which she lived. One observer called her ‘une beauté tyrannique’.9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Her unhappiness was given an edge of anger when she discovered that her taciturn husband had taken another mistress, and one whom he seemed genuinely to love. Melusine von Schulenberg had none of Sophia Dorothea’s physical attractions – she was tall and thin, nicknamed ‘the scarecrow’ by George’s mother – but she was calm, malleable and good-natured, in contrast to Sophia Dorothea’s more febrile character. She sought to manage George’s moods, and make his life easier, whilst his wife seemed only to cause him difficulties. Sophia Dorothea was bitterly humiliated by her husband’s public preference for a woman far less beautiful and of lower social status than herself, and she refused to adopt the wronged wife’s traditional stance of dignified resignation. She scolded her resentful husband, made scenes at court, and complained to her father-in-law. In doing so, not only did she earn the lasting resentment of George’s mother (who could not see why she should not submit quietly to marital infidelity, as she had done), but also made enemies of the powerful Platen women, who disliked Sophia Dorothea’s wilder accusations against mistresses and their wiles. Unhappy, rejected and isolated amongst people who were embarrassed and annoyed by her indiscreet outbursts, Sophia Dorothea was in a very vulnerable state. It is perhaps not surprising that she was so quickly persuaded to do the very worst and dangerous thing she could have done in such circumstances: fall in love with another man.

It was at this inauspicious moment that ‘the famous and beautiful’ Count Philip von Königsmark arrived at the Hanoverian court. He was a Swedish aristocrat, rich, handsome, clever, witty and assured, an archetypal sophisticated bad boy who had gambled, fought and drunk his way across Europe before enlisting as an officer in the Hanoverian service. He was everything Sophia Dorothea’s dour husband was not, and was obviously attracted to her. They enjoyed each other’s company, and when he left to join the army, he began to write to her. Soon the letters they exchanged were those of lovers. At first, they were careful – ‘If I were not writing to a person for whom my respect is as great as my love,’ wrote Königsmark, ‘I should find better terms to express my passion’ – but as their relationship grew more intense, they became less discreet.10 (#litres_trial_promo)

When Königsmark returned, they snatched meetings in corridors, and exchanged glances in ballrooms. People noticed. They became the object of gossip, spread avidly by the Platens. Eventually, even Sophia Dorothea’s mother heard the talk, and begged her daughter to break off the affair. She refused, and for over two years sustained her love for the count through occasional meetings and lengthy correspondence, in which she did not hesitate to declare the strength of her feelings, even confessing she would like to abandon her empty, unsatisfactory life. ‘I thought a thousand times of following you,’ she wrote, ‘what would I not give to be able to do it, and always be with you. But I should be too happy and there is no such bliss in this world.’11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Yet for all her declaration of its impossibility, the idea of starting a new life with Königsmark became an obsession for her. By 1694, both her parents were aware that she wanted to end her twelve-year marriage. Rumours of an impending elopement transfixed the court. Königsmark’s recent appointment as commander of a Saxon regiment seemed to offer the couple both the resources and the opportunity to run away together.

Then in July events came to a sudden and horrible conclusion. Whilst drunk, Königsmark was heard publicly discussing the affair; as a result, he was ordered, allegedly by Ernst August himself, to leave Hanover that very night. He was then seen entering the palace, apparently to say goodbye to his lover. Horace Walpole later heard that with the assistance of Sophia Dorothea’s ladies, ‘he was suffered to kiss her hand before his abrupt departure, and was actually introduced by them into her bedchamber the next morning before she rose’.12 (#litres_trial_promo) Others maintained he never reached his rendezvous. What is certain is that after his late-night arrival at the Leine palace, Königsmark was never seen again.

Exactly what happened to him remains a mystery. It was widely suspected he had been murdered; his remains were supposed to have been thrown into a river in a sack weighted with stones.13 (#litres_trial_promo) Nothing was ever definitively proved, and rumours concerning Königsmark’s fate circulated around the princely courts of Europe for years. Walpole, however, believed he knew the truth. A generation later, when Sophia Dorothea’s son George II ordered alterations to be made to his mother’s old apartments at Leine, Walpole was told that the builders made a gruesome discovery: ‘The body of Königsmark was discovered under the floor of the Electoral Princess’s dressing room, the count probably having been strangled the instant he left her, and his body secreted there.’14 (#litres_trial_promo) This discreditable story was, asserted Walpole, ‘hushed up’, but he claimed that his father, Sir Robert, had heard it directly from George II’s wife, Queen Caroline.

Whatever Königsmark’s fate, it is hard to believe that Ernst August played no part in it. The payment of large sums of money by Ernst to a small group of loyal courtiers shortly after the event seems more than coincidental. Ernst certainly had sufficient motive at least to connive at the killing. After a lifetime of planning and scheming, he had finally achieved the coveted status of elector only two years before, in 1692. The humiliation of his son at the hands of an adulterous wife did not form part of his plan for the continued upward rise of his family’s power and influence. It is unlikely, however, that his role in the affair will ever finally be established. The role played by Sophia Dorothea’s husband in her lover’s disappearance is even harder to assess. Perhaps intentionally, George was away from court at the time of Königsmark’s disappearance. But if he was ignorant of any plans to dispose of the count, he was fully complicit in what now happened to his wife.

Sophia Dorothea was hustled away to a remote castle at Ahlden, Lower Saxony, where she was kept isolated in the strictest confinement. Letters from her were found at Königsmark’s house, and shown to her father who, as a result of what they disclosed, effectively abandoned her. Her mother was refused access to her. Immured alone at Ahlden, she was questioned over and over again about the precise nature of her relationship with Königsmark. She always denied that she had committed what she called ‘le crime’, but the couple’s correspondence contradicted her assertions. In them, Königsmark made it clear how much he hated the thought of Sophia Dorothea having sex – or, as he put it, ‘monter à cheval’ – with her husband. In her replies, Sophia Dorothea reassured him that George was a very poor lover in comparison with himself, and added vehemently that she longed for George to die in battle. It is probable that George was shown these letters, which may explain some of the harshness with which Sophia Dorothea was treated in the months that followed.15 (#litres_trial_promo)

At first, it was hard to know what to do with George’s errant wife. In the end, she was persuaded to become the unwitting author of her own misery. She was encouraged to ask for a separation from her husband, which she did almost willingly, on the grounds that ‘she despaired of ever overcoming the aversion the prince has for several years evinced towards her’.16 (#litres_trial_promo) It is unlikely she knew at this stage that Königsmark was dead; naively, she may still have hoped to be reunited with him after a separation had taken place. Armed with his wife’s declaration, in December 1694, George was quickly able to obtain a divorce. Sophia Dorothea hoped that afterwards she would be allowed quietly ‘to retire from the world’, expecting to live with her mother at Celle; instead she was returned to Ahlden, where she was locked up and, in all but name, imprisoned.

Any reminders of Sophia Dorothea’s presence were ruthlessly and systematically erased from the Hanoverian court. Her name was struck out of prayers, and all portraits of her taken down. She had become a non-person, and disappeared into a confinement from which she would never emerge. She had not been allowed to say goodbye to her children – twelve-year-old George and seven-year-old Sophia Dorothea – before she was taken away. She would not see them again. Her name was never mentioned to them, and they were forbidden to speak of her. She was permitted to take portraits of them with her, which she regarded as her most precious possessions. When Ernst August died, and her ex-husband inherited his title, she wrote to him, begging to be allowed to see her children. He did not reply. ‘He is so cold, he turns everything to ice,’ commented the Duchess of Orléans sadly.

For the first two years, Sophia Dorothea was held entirely inside the Ahlden castle. Later, she was able to walk outside for half an hour a day. George did not deprive her of money and she lived in some luxury, dressed in the fashionable clothes she had always loved. There were few people to admire them, however. No visitors were permitted. Sophia’s only contact with her family was through the eighty-one pictures of her relations that she had hung on her walls, including one of her ex-husband. She did not read a letter that had not been scrutinised by her gaoler first. Surrounded by a small entourage of elderly ladies, Sophia went nowhere unattended. The boredom of her life seems to have overwhelmed her, and she sought sensation wherever she could find it. On rare outings in her state carriage, she always asked to have the horses driven at the highest possible speed. Her mother, who had been tireless in her appeals to see her daughter, was eventually allowed to visit her; but after her death, Sophia Dorothea saw no one. In 1714, when George crossed the North Sea to take up his new responsibilities in Britain, it was suggested to him that he might now relax the conditions under which his ex-wife dragged out her existence; but he was implacable. Sophia Dorothea endured this shadow of a life for thirty-one years. In 1726, she became seriously ill. Her attendants tried to raise her spirits by showing her the portraits of her children, but when this much relied-upon source of comfort failed, they realised she was dying. A few days later, she was dead.

If George was troubled by guilt at any point throughout her long exile, he gave no sign of it. He never commented on his ill-starred marriage, nor its tragic end. He did not marry again, but lived in apparently placid contentment with Melusine von Schulenberg, whom he later ennobled as the Duchess of Kendal.

Yet there remained in George’s carefully preserved, quiet life an unignorable reminder of a partnership he had never wanted, and which had caused him such public humiliation. The two children he had fathered with Sophia Dorothea could not be expunged or denied. His daughter he seems to have regarded benignly, although she played almost no part in his daily life; but his relationship with his son could not be similarly consigned to the margins of his public world. As his heir, the young Prince George represented a dynastic and political fact which George was compelled to acknowledge. But he could not – and would not – be brought to love the boy.