По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

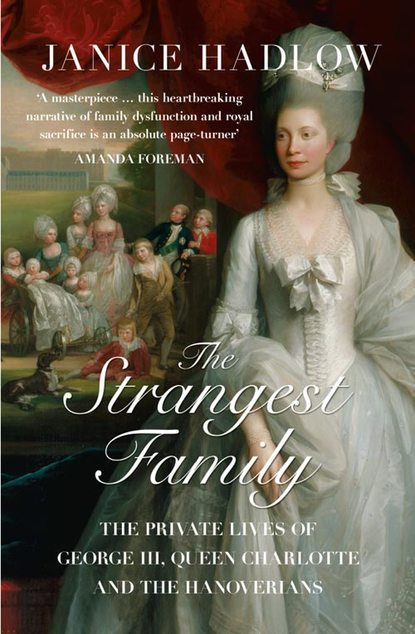

The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In 1746, Bute left his island and headed south, hoping perhaps to improve his financial prospects. Once in London, he was soon noticed, but it was not the power of his mind that attracted attention. ‘Lord Bute, when young possessed a very handsome person,’ recalled the politician and diplomat Nathaniel Wraxall, ‘of which advantage he was not insensible; and he used to pass many hours a day, as his enemies asserted, occupied in contemplating the symmetry of his own legs, during his solitary walks by the Thames.’81 (#litres_trial_promo) Bute’s portraits – in which his legs are indeed always displayed to advantage – confirm that he was a very attractive man. Tall, slim and with a dark-eyed intensity of expression, it is not hard to see why he was so sought after. It may have been his looks that caught the eye of the Prince of Wales. It was said that Bute first met Frederick at Egham races, when the prince invited him in from a rainstorm to join the royal party at cards. Soon he was a regular attendee at all the prince’s parties, and had unbent sufficiently to play the part of Lothario in one of Frederick’s private theatrical performances. The prince seemed to enjoy his company, and Bute was admitted to the inner circle of his court. Walpole asserted that Frederick eventually grew tired of Bute’s pretensions, ‘and a little before his death, he said to him, “Bute, you would make an excellent ambassador in some proud little court where there is nothing to do.”’82 (#litres_trial_promo) But whatever his occasional frustrations, Frederick thought enough of the earl to make him a Lord of the Bedchamber in his household, and it was only the prince’s sudden demise that seemed to put an end to Bute’s ambitions, as it did to those of so many others.

After Frederick’s death, Bute stayed in contact with his widow. Augusta shared his botanical interests, and he advised her on the planting of her gardens at Kew. He is never mentioned in Dodington’s diary, perhaps because Dodington correctly identified him as a rival for Augusta’s confidence. As the years passed, Bute’s influence grew and grew, until, by 1755, he had supplanted Dodington and all other contenders for the princess’s favour. He had also won over her son, and without telling anyone, least of all the king, Augusta quietly instructed Bute to begin acting as George’s tutor. For all his experience in the ways of courts, Waldegrave, the official incumbent, seems to have had no idea what was happening until it was too late. Once he realised just how thoroughly he had been supplanted, Waldegrave was determined to leave with as much dignity as he could muster. The king pressed Waldegrave to stay. He was resolutely opposed to the inclusion of Bute – an intimate of Frederick’s – in the household of his grandson, particularly in a position of such influence; but Waldegrave knew there was nothing to be done. In 1756, the prince reached the age of eighteen and could no longer be treated as a child. Reluctantly, the king bowed to the inevitable, and Bute was appointed Groom of the Stole, head of the new independent establishment set up for George. To show his displeasure, the king refused to present Bute with the gold key that was the badge of his new office, but gave it to the Duke of Grafton – who slipped it into Bute’s pocket and told him not to mind.

When Horace Walpole wrote his highly partisan account of the early reign of George III, he maintained that there was far more to Bute’s appointment than anyone had realised at the time; it was, he claimed, the opening act in a plot aimed to do nothing less than suborn the whole constitution. In Walpole’s version of events, Augusta and Bute – ‘a passionate, domineering woman and a favourite without talents’ – conspired together to bring down the established political settlement. They intended first to indoctrinate the supine heir with absolutist principles, and then to marginalise him by ensuring his isolation from the world. All this was to be achieved in the most gradual and surreptitious manner. Ignorant and manipulated, George would remain as titular head of state; but behind him, real power would reside in the hands of Bute and Augusta. To add an extra frisson to a story already rich in classical parallels, Walpole insisted that Augusta and Bute were lovers, ‘his connection with the princess an object of scandal’. Elsewhere he was more blunt, declaring: ‘I am as much convinced of an amorous connexion between Bute and the princess dowager as if I had seen them together.’83 (#litres_trial_promo)

Related with all the passion he could muster, in Walpole’s hands this proved to be a remarkably potent narrative. For nearly two hundred years, until interrogated and revised by the work of twentieth-century historians, it was to influence thinking about George’s years as Prince of Wales and as a young king; and the reputations of Bute and Augusta are still coloured by Walpole’s bilious account of their alleged actions and motives. But in writing the Memoirs, Walpole’s purpose was scarcely that of a disinterested historian. First and foremost, he wrote to make a political point. Walpole was a Whig, passionately opposed to what he saw as the autocratic principles embraced by his Tory opponents, who, he had no doubt, desired nothing so much as to restore the pretensions and privileges of the deposed Stuarts. He was, he said, not quite a republican, but certainly favoured ‘a most limited monarchy’, and was perpetually on the lookout for evidence of plots hatched by the powerful and unscrupulous to undermine the hard-won liberties of free-born Britons. To that extent, the Memoirs, couched throughout in a tone of shrill outrage quite unlike Walpole’s accustomed smooth, ironic style, are best considered as a warning of what might happen rather than an account of what did – a chilling fable of political nightmare designed to appal loyal constitutionalists. Less portentously, Walpole also wrote to pay off a grudge. He considered he had been wronged by Bute, who had refused to grant him a sinecure Walpole believed he was owed: ‘I was I confess, much provoked by this … and took occasion of fomenting ill humour against the favourite.’84 (#litres_trial_promo)

Much of what resulted from this incendiary combination of intentions was simply nonsense, and often directly contradicted what Walpole had himself written in earlier days. In truth, there was no plot; Augusta was not ‘ardently fond of power’; neither she nor Bute was scheming to overturn the constitution; and it is extremely unlikely that they were lovers. But if the central proposition of Walpole’s argument was a fiction, that did not mean that everything he wrote was pure invention. The Memoirs exerted such a powerful appeal because Walpole drew on existing rumours that were very widely believed at the time; and because, sometimes, beneath Walpole’s wilder assertions there lay buried a tiny kernel of truth.

Thus, Walpole seemed on sure ground when describing the isolation in which George had been brought up, and the extraordinary precautions taken to keep him away from wider intercourse with the world. He was correct in his assertion that much of this policy had been driven by Augusta. He was wrong about her motives – the extreme retirement she imposed on her son was a protective cordon sanitaire, not a covert means of dominating him – but the prince’s isolation was observable to everyone in the political world, and of as much concern to Augusta’s few allies as it was to her enemies. Walpole was also right to assert that within the secluded walls of Kew and Leicester House, the future shape of George’s kingship was indeed the subject of intense discussion; but these reflections were directed towards an outcome very different from Walpole’s apocalyptic image of treasonous constitutional conspiracy. Finally, he was accurate in his suspicion that there was a passionate relationship at the heart of the prince’s household. But it was not, in fact, the one he went on to describe with such relish.

The stories about Bute and Augusta had been in circulation long before Walpole’s Memoirs appeared. Waldegrave, who never forgot or forgave the way he was humiliatingly ejected from his post around the prince, seems to have been the origin of many of them. ‘No one of the most inflammable vengeance, or the coolest resentment could harbour more bitter hatred than he did for the king’s mother and favourite,’ wrote Walpole with a hint of appalled admiration.85 (#litres_trial_promo) For the rest of her life, as a result of these rumours, Augusta was mercilessly pilloried as a brazen adulteress; in newspapers, pamphlets, and above all in satirical caricatures, she was depicted as Bute’s mistress. One print showed her as a half-naked tightrope walker, skirt hitched up to her thighs, suggestively penetrated by a pole with a boot (a play on Bute’s name) attached to it. It was hardly surprising that Prince George was horrified ‘by the cruel manner’ in which his mother was treated, ‘which I will not forget or forgive till the day of my death’.86 (#litres_trial_promo)

However, for all the salacious speculation surrounding their relationship, it seems hard to believe that Bute and Augusta ever had an affair. Although Augusta clearly admired the attractive earl, writing to him with an enthusiasm and warmth that few of her other letters betray, to embark on anything more than friendship would have been quite alien to her character. She was too cautious, too conscious of her standing in the world, too controlled and reserved to have taken the extraordinary risk such a relationship would have entailed. But, in the complex interplay of the political and the personal that transformed the tone of Augusta’s family in the latter years of the 1750s, there was one person who surrendered himself entirely to an unexpected and completely overpowering affection. The diffident young Prince George had finally found someone to love.

Bute had been acting as George’s informal tutor for less than a year before it was plain that he had achieved what no one had been able to do before: win the trust and affection of the withdrawn prince. Augusta was delighted. ‘I cannot express the joy I feel to see he has gained the confidence and friendship of my son,’ she wrote in the summer of 1756, with uncharacteristically transparent pleasure.87 (#litres_trial_promo) The prince himself was equally fervent, writing almost ecstatically to Bute that ‘I know few things I ought to be more thankful to the Great Power above, than for having pleased Him to send you and help me in these difficult times.’88 (#litres_trial_promo)

This was the first of many letters the prince wrote to Bute over nearly a decade; its tone of incredulous gratitude, its sense of sheer good fortune at the very fact of Bute’s presence, was one that would be replicated constantly over the years. Their correspondence illuminates the painful intensity of George’s feelings for the earl, from his speedy capitulation to the onslaught of Bute’s persuasive charm, to the submissive devotion that characterised the prince’s later relationship with this charismatic, demanding and sometimes mercurial figure. George’s letters also offer a remarkably candid picture of his state of mind as a young man. He opened his heart to Bute in a way he had done to no one before, and would never do again after he and the earl had parted. Many of his letters make uncomfortable reading; they reveal an isolated and deeply unhappy character, consumed by a sense of his own inadequacies, and desperate to find someone who would lead him out of the fog of despair into which he was sinking. George knew he was drifting, fearful and rudderless, towards a future which approached with a horrible inevitability. He was very quickly convinced that Bute was the only person who could deliver him from the state of paralysed inertia in which he had existed since his father’s death. ‘I hope, my dear Lord,’ he wrote pleadingly, ‘you will conduct me through this difficult road and bring me to the goal. I will exactly follow your advice, without which I will inevitably sink.’89 (#litres_trial_promo)

He knew he needed someone to supply the determination and resilience in which he suspected he was so shamefully deficient. He was delighted – and profoundly relieved – to find a mentor to whom he could surrender himself absolutely, to whose better judgement he could happily submit. Without such a guide, he believed his prospects looked bleak indeed. ‘If I should mount the throne without the assistance of a friend, I should be in the most dreadful of situations,’ he assured the earl in 1758.90 (#litres_trial_promo)

Bute also offered George genuine warmth and affection. His enthusiastic declarations of regard, his energetic and apparently disinterested commitment to his wellbeing, exploded into the prince’s arid, sentimental life. George’s devotion to Bute soon became the most important relationship in his life. ‘I shall never change in that, nor will I bear to be the least deprived of your company,’ he insisted vehemently.91 (#litres_trial_promo) The growing intensity of the prince’s feelings was reflected not just in the content of his letters to Bute, but also in the way he addressed him. At first, he was ‘my dear Lord’, a term of conventional courtly politeness; soon this warmed into ‘my dear Friend’; but very quickly, the strength of the prince’s feelings were made even plainer. All obstacles, he wrote to the earl with unembarrassed devotion, could and would be overcome, ‘whilst my Dearest is near me’.92 (#litres_trial_promo) Bute was not just mentor and role model to the prince; he was also the first person to unearth George’s hitherto deeply buried but strong emotions.

Bute broke through the prince’s habitual reserve partly by what he did, and partly by who he was. He was a compellingly attractive figure to a fatherless, faltering boy: handsome, assured and experienced, he was everything George knew he was not. Augusta, who was suspicious of almost everyone, admired and respected Bute, and the earl was unequivocal in his praise of George’s dead father, declaring that he had gloried in being known as Frederick’s friend. Unlike many of his predecessors, Bute actually seemed to like the prince, and he approached the prospect of training him for kingship with a galvanising enthusiasm. ‘You have condescended to take me into your friendship,’ he told the prince, ‘don’t think it arrogance if I say I will deserve it.’93 (#litres_trial_promo) Bute’s breezy optimism about the task before him was in stark contrast to the dour resignation of previous instructors. ‘Use will make everything easy,’ he confidently assured his faltering charge.94 (#litres_trial_promo)

Leaving Latin behind at last, George and Bute embarked on a course of more contemporary study. Bute encouraged the prince to investigate finance and economics, and together they read a series of lectures by the jurist William Blackstone that was to form the basis of his magisterial work on the origins of English common law. Bute even ventured confidently where Andrew Stone had feared to tread. George’s essay, ‘Thoughts on the English Constitution’, included opinions that might have reassured Walpole, had he read it, so impeccably Whiggish were its sentiments. The Glorious Revolution had, the prince wrote, rescued Britain ‘from the iron rod of arbitrary power’, while Oliver Cromwell was described, somewhat improbably by the heir to the throne, as ‘a friend of justice and virtue’.95 (#litres_trial_promo)

Whilst Bute’s more liberal definition of ‘what is fit for you to know’ undeniably piqued George’s interest, it was his bigger ideas that consolidated his hold over the prince and secured his pre-eminent place in George’s mind and heart. The most significant of these was one which would transform the prince’s prospects and offer him a way out of the despondency that had threatened to overwhelm him since his father’s death. In the late 1750s, Bute proposed nothing less than a new way of understanding the role of monarchy, offering George an enticingly credible picture of the kind of ruler he might aspire to become. For the first time he was presented with a concept of kingship that seemed within his capacity to achieve, that spoke to his strengths rather than his failings. It changed the nature of George’s engagement, not just with Bute but, more significantly, with himself. It gave him something to aim for and believe in; the delivery of this vision was ‘the goal’ that George believed was the purpose of his partnership with Bute. Indeed, it far outlasted his relationship with the earl; until his final descent into insanity half a century later, it established the principles by which he lived his life as a public and private man.

In Bute’s ideal, the role of the king was not simply to act as an influential player in the complex interplay of party rivalry that dominated politics in mid-eighteenth-century Britain. It was the monarch’s job to rise above all that, to transcend faction and self-interest, and devote himself instead to the impartial advancement of the national good. This was not an original argument; it derived from Henry, Viscount Bolingbroke’s extremely influential Idea of a Patriot King, written in 1738 (though not published until 1749). Frederick had been much taken with Bolingbroke’s ideas, and the ‘Instructions’ he wrote as a political testimony for his son drew strongly on many of Bolingbroke’s conclusions, but Frederick was primarily concerned with the practical political implications of Bolingbroke’s ideas. The ‘Instructions’ is mostly a list of recommendations intended to secure for a king the necessary independence to escape the control of politicians, most of which revolve around money: don’t fight too many wars, and separate Hanover, a drain on resources, from Great Britain as soon as possible.

Bute too was interested in the exercise of power; but, always drawn towards philosophy, he was even more fascinated by its origins, and sought to formulate a coherent, modern explanation for the very existence of kingship itself. Choosing those measures which best reflected the ambitions of a ‘patriot’ king was secondary, in his mind, to establishing the justification by which such a king held the reins of government in the first place. For Bute, the answer was simple: it was the virtue of the king – the goodness of his actions, as both a public and a private man – that formed the source of all his power. Virtue was clearly the best protection for an established ruler; a good king was uniquely positioned to win the love and loyalty of his people, making it possible for him to appeal credibly to the sense of national purpose that went beyond the narrower interests of party politicians. But the connection between morals and monarchy went deeper than that. Virtue was not just an attribute of good kingship; it was also the quality from which kings derived their authority. And the virtues Bute had in mind were not cold civic ones peculiar to the political world, of necessity and expediency. They were the moral standards which all human beings were held to, those which regulated the actions of all decent men and women. Kingship offered no exemption from moral conduct; on the contrary, more was expected of kings because so much more had been given to them. Moral behaviour in the public realm was therefore indivisible from its practice in the private world. To be a good king, it was essential to try to be a good man.

The place where private virtue was most clearly expressed, for Bute as for most of his contemporaries, was within the family. Here, in the unit that was the basic building block of society, the moral life was most easily and most rewardingly to be experienced. The good king would naturally enjoy a family life based on shared moral principles. Indeed, for Bute, authority had itself actually originated within the confines of the family. ‘In the first ages of the world,’ as he explained to George, private and public virtue had been one and the same thing; in this pre-political Eden, there was no distinction between the two, as government and family were not yet divided: ‘Parental fondness, filial piety and brotherly affection engrossed the mind; government subsisted only in the father’s management of the family, to whom the eldest son succeeding, became at once the prince and parent of his brethren.’

Everything began to go wrong when families lost their natural moral compass: ‘Vice crept in. Love, ambition, cruelty with envy, malice and the like produced unnatural parents, disobedient children, diffidence and hatred between near relations.’ It all sounded remarkably like the home lives of George’s Hanoverian predecessors, as Bute perhaps intended that it should. The failure of self-regulating family virtue forced men to create artificial forms of authority – ‘hence villages, towns and laws’ – but as communities grew bigger, their rulers moved further and further away from the moral principles that were the proper foundation of power. The consequences were dire, both for the ruled and their rulers: ‘Unhappy people, but more unhappy kings.’96 (#litres_trial_promo) The amoral exercise of power ruined those who practised it. ‘They could never feel the joy arising from a good and compassionate action … they could never hear the warm, honest voice of friendship, the tender affections and calls of nature, nor the more endearing sounds of love, but here, the scene’s too black, let me draw the curtain.’97 (#litres_trial_promo)

For Bute, the lesson of history was clear: good government originated in the actions of good men. What was needed now, he concluded, was a return to such fundamental first principles. He summed up his programme succinctly: ‘Virtue, religion, joined to nobility of sentiment, will support a prince better and make a people happier than all the abilities of an Augustus with the heart of Tiberius; the inference I draw from this is, that a prince ought to endeavour in all his thoughts and actions to excel his people in virtue, generosity, and nobility of sentiment.’ This is the source of his authority and the justification for his rule. Only then will his subjects feel that ‘he merits by his own virtue and not by the fickle dice of fortune the vast superiority he enjoys above them’.98 (#litres_trial_promo)

George embraced Bute’s thinking enthusiastically – and also perhaps with a sense of relief. He might have doubts about his intellectual capacity, and about his ability to dominate powerful and aggressive politicians, but he was more confident of legitimising his position by the morality of his actions. He suspected he was not particularly clever, but he was enough of his mother’s son to believe that he could be good – and perhaps more so than other men. He grasped at this possibility, and never let it go. It rallied his depressed spirits, jolted him out of a near-catatonic state of despair. It gave him a belief in himself and an explanation for his strange and unsettling destiny. It invested his future role with a meaning and significance it had so profoundly lacked before.

Bute’s vision of kingship transformed George’s perception of his future and shaped his behaviour as a public man for the rest of his life. Inevitably, it also dictated the terms on which his private life was conducted. He was unsparing in his interpretation of what the virtuous life meant for a king. He rarely flinched from the necessity to do the right rather than the pleasurable or easy thing, and he insisted on the absolute primacy of duty over personal desire and obligation over happiness. In time, these convictions came to form the essence of his personality, the DNA of who he was; and when he came to have a family, the lives of his wife and children were governed by the same rigorous requirements of virtue. As a father, a husband, a brother or a son, he was answerable to the same immutable moral code that governed his actions as a king. Bute taught him that in his case, the personal was always political; and it was a lesson he never forgot.

All this was to come later, however. When he took up his post, Bute was acutely aware of just how far short his charge fell from the princely ideal that was the central requirement of his monarchical vision. From the moment of his arrival, he set out to rebuild the prince’s tentative, disengaged personality, using a potent combination of threat and affection to do so. His first target was the prince’s lethargy, the subject of so much ineffectual criticism from Waldegrave and previous tutors. Bute was tenacious in his attempts to persuade George to show some energy and commitment to his studies; but it was a slow process, and one which required all the earl’s considerable powers of persuasion. By 1757, he had begun to make some progress, and the prince assured him: ‘I do here in the most solemn manner declare that I will entirely throw aside this my greatest enemy, and that you shall instantly find a change.’99 (#litres_trial_promo) It was not just George’s academic dilatoriness that Bute sought to tackle; he also attempted to root out other potentially damaging aspects of his personality that might compromise his authority when he came to be king. His pathological and disabling shyness must and would be conquered. Again, George declared himself ready to take up the challenge. He promised Bute that he was now determined to ‘act the man in everything, to repeat whatever I am to say with spirit and not blushing and afraid as I have hitherto’.100 (#litres_trial_promo)

Although George confessed he was sometimes ‘extremely hurt, at the many truths’ Bute told him, he did not doubt that Bute’s ‘constant endeavours to point out these things in me that are likely to destroy any attempts at raising my character’ were for his own good, ‘a painful, though necessary office’.101 (#litres_trial_promo) They were also, in George’s eyes, a sign of the depth of Bute’s regard for him, since only someone who really loved him would be prepared to criticise him so readily. ‘Flatterers, courtiers or ministers are easily got,’ his father had explained to him in his ‘Instructions’, ‘but a true friend is hard to be found. The only rule I can give you to try them by, is that they will tell you the truth.’ If George discovered such an honest man, he should do all he could to keep him, even if that required him to bear ‘some moments of disagreeable contradictions to your passions’.102 (#litres_trial_promo)

George had no difficulty in submitting to Bute’s comprehensive programme of self-improvement, sadly convinced that all the criticisms were deserved. His opinion of himself could not have been lower. He was, he confessed, ‘not partial to myself’, regularly describing both his actions and himself as despicable. ‘I act wrong perhaps in most things,’ he observed, adding that he might be best advised to ‘retire, to some distant region where in solitude I might for the rest of my life think on the faults I have committed, that I might repent of them’.103 (#litres_trial_promo) He was afraid that he was ‘of such an unhappy nature, that if I cannot in good measure alter that, let me be ever so learned in what is necessary for a king to know, I shall make but a very poor and despicable figure’.104 (#litres_trial_promo) When he contemplated his many shortcomings and failures, he was amazed that Bute was prepared to remain with him at all.

The idea that Bute might leave – that his patience with his underachieving charge might exhaust itself – threw the prince into paroxysms of anxiety. Bute seems often to have deployed the idea of potential abandonment as a means of reminding George of the totality of his dependency. The merest suggestion of it was enough, George admitted, to ‘put me on the rack’, declaring that the prospect was ‘too much for mortal man to bear’.105 (#litres_trial_promo) His self-esteem was so low that George was sure that if Bute were to depart, he would have only himself to blame. ‘If you should resolve to set me adrift, I could not upbraid you,’ he wrote resignedly, ‘as it is the natural consequence of my faults, and not want of friendship in you.’106 (#litres_trial_promo) George was endlessly solicitous about Bute’s health: the possibility of losing him through illness or even death was a horrifying prospect that loomed large in George’s nervous imagination; his letters are full of enquiries and imprecations about the earl’s wellbeing. When Bute and his entire family fell seriously ill with ‘a malignant sore throat’, the prince was beside himself with worry. He took refuge in his conviction that ‘you, from your upright conduct, have some right to hope for particular assistance from the great Author of us all’.107 (#litres_trial_promo) It was inconceivable that God would not value Bute’s virtues as highly as George did; when the earl recovered, George presented his doctors with specially struck gold medals of himself to mark his appreciation of their care.

From the mid-1750s to the time of his accession, the entire object of George’s existence was to reshape and remodel himself into the type of man who could fulfil the role of king, as Bute had so alluringly redefined it; but this internal reformation was not accompanied by a change in his way of life. He remained closeted at home with his mother and the earl, and for all Bute’s desire to reform the prince’s personality, he left many of George’s deepest beliefs untouched – partly because he shared some of them himself. One of the reasons George found Bute so congenial was because he endorsed so much of the vision of the world that the prince had inherited from his mother. For all his confidence in the righteousness of his prescriptions, and for all the energy and enthusiasm with which he argued them, there was in Bute himself a core of austerity and reserve. He was not a naturally sociable man, preferring to judge society – often rather severely – than to engage with it. He had a natural sympathy with the suspicion and apprehension with which Augusta encountered anything beyond the narrow bounds of her immediate family. He offered George no alternative perspective, but instead confirmed the prince’s pessimism about the moral worth and motives of others, a bleak scepticism that was to endure throughout his life. ‘This,’ wrote George, ‘is I believe, the wickedest age that ever was seen; an honest man must wish himself out of it; I begin to be sick of things I daily see; for ingratitude, avarice and ambition are the principles men act by.’108 (#litres_trial_promo)

Bute’s counsels did nothing to dilute the mix of fear and contempt with which the prince contemplated the world he must one day join. ‘I look upon the majority of politicians as intent on their own private interests rather than of the public,’ George wrote with grim certainty.109 (#litres_trial_promo) William Pitt, his grandfather’s minister, was ‘the blackest of hearts’. His uncle, Cumberland, was still, George believed, capable of mounting a coup d’état to prevent his accession: ‘in the hands of these myrmidons of the blackest kind, I imagine any invader with a handful of men might put himself on the throne and establish despotism here’.110 (#litres_trial_promo) He had fully absorbed Augusta’s deep-seated hostility to his grandfather and, like her, could not find a good word to say about ‘this Old Man’. George II’s behaviour was ‘shuffling’ and ‘unworthy of a British monarch; the conduct of this old king makes me ashamed of being his grandson’.111 (#litres_trial_promo) There was only one man deserving of George’s confidence, and that was Bute. ‘As for honesty,’ he told Bute, ‘I have already lived long enough to know you are the only man I shall ever meet who possesses that quality and who at all times prefers my interest to their own; if I were to utter all the sentiments of my heart on that subject, you would be troubled with quires of paper.’112 (#litres_trial_promo)

By 1759, Bute’s ascendancy over the prince seemed complete. The prospect of translating their political ideas into practice once George II was dead offered a beacon of hope which sustained them through adversity – it had been agreed at the very outset of their relationship that Bute was to become First Lord of the Treasury when George was king. But in that year, the earl’s authority was challenged from a direction that neither he and nor perhaps George himself had anticipated.

*

In the winter, conducting one of his regular inventories of George’s state of mind, Bute became convinced the prince was hiding something from him. Pressed to declare himself, George was cautious at first, but eventually began a hesitant explanation of his mood. At first, he confined himself to generalities. ‘You have often accused me of growing grave and thoughtful,’ he confessed. ‘It is entirely owing to a daily increasing admiration of the fair sex, which I am attempting with all the philosophy and resolution I am capable of, to keep under. I should be ashamed,’ he wrote ruefully, ‘after having so long resisted the charms of those divine creatures, now to become their prey.’113 (#litres_trial_promo) There was no doubt that the twenty-one-year-old George was still a virgin. His younger brother Edward, far more like his father and grandfather in his tastes, had eagerly embarked on affairs as soon as he had escaped the schoolroom, but George had thus far remained true to his mother’s principles of self-denial and restraint. Walpole believed that if she could, Augusta would have preferred to keep her son perpetually away from the lures of designing women: ‘Could she have chained up his body as she did his mind, it is probable that she would have preferred him to remain single.’ But the worldly diarist thought he knew the Hanoverian temperament well enough to be convinced this was an impossible objective. ‘Though his chastity had hitherto remained to all appearances inviolate, notwithstanding his age and sanguine complexion, it was not to be expected such a fast could be longer observed.’114 (#litres_trial_promo) Certainly this was how the prince himself felt, confessing to Bute that he found repressing his desires harder and harder. ‘You will plainly feel how strong a struggle there is between the boiling youth of 21 years and prudence.’ He hoped ‘the last will ever keep the upper hand, indeed if I can but weather it, marriage will put a stop to this conflict in my breast’.115 (#litres_trial_promo)

As Bute suspected, George’s disquiet reflected something more than a general sense of frustration. Incapable of concealing anything of importance from Bute, he wrote another letter which confessed all. ‘What I now lay before you, I never intend to communicate to anyone; the truth is, the Duke of Richmond’s sister arrived from Ireland towards the middle of November. I was struck with her first appearance at St James’s, and my passion has increased every time I have since beheld her; her voice is sweet, she seems sensible … in short, she is everything I can form to myself lovely.’ Since then, his life had hardly been his own: ‘I am grown daily unhappy, sleep has left me, which was never before interrupted by any reverse of fortune.’ He could not bear to see other men speak to her. ‘The other day, I heard it suggested that the Duke of Marlborough made up to her. I shifted my grief till I retired to my chamber where I remained for several hours in the depth of despair.’ His love and his intentions were, he insisted, entirely honourable: ‘I protest before God, I never have had any improper thoughts with regard to her; I don’t deny having flattered myself with hopes that one day or another you would consent to my raising her to a throne. Thus I mince nothing to you.’116 (#litres_trial_promo)

Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond (which title her brother inherited), was almost as well connected as George himself. Her grandfather was a son of Charles II and his mistress Louise de Kérouaille. She had four sisters, three of whom had done very well in the marriage market. The eldest, Caroline, was wife to the politician Henry Fox, and mother to Charles. Emily had married the Earl of Kildare, and Louisa had made an alliance with an Irish landowner, Thomas Connolly. From her youth, Sarah was one of the liveliest members of a famously lively family. As a very small child, she had caught the eye of George II. He had invited her to the palace where she would watch the king at his favourite pastime, ‘counting his money which he used to receive regularly every morning’. Once, with heavy-handed playfulness, he had ‘snatched her up in his arms, and after depositing her in a large china jar, shut down the lid to prove her courage’.117 (#litres_trial_promo) When her response was to sing loudly rather than to cry, he was delighted.

When her mother died, Sarah went to live with her sister, Lady Kildare, in Ireland. She did not return to court until she was fourteen. George II, who had not forgotten her, was pleased to see her back, but ‘began to joke and play with her as if she were still a child of five. She naturally coloured up and shrank from this unaccustomed familiarity, became abashed and silent.’ The king was disappointed and declared: ‘Pooh! She’s grown quite stupid!’118 (#litres_trial_promo)

Those who found themselves on the receiving end of his grandfather’s insensitivity aroused the sympathy of the Prince of Wales. ‘It was at that moment the young prince … was struck with admiration and pity; feelings that ripened into an attachment which never left him until the day of his death.’119 (#litres_trial_promo) That was the account Sarah gave to her son in 1837, and which he transcribed with reverential filial piety. In letters she wrote to her sisters at the time, Sarah was not so sentimental. After her first meeting with George, she described her clothes – blue and black feathers, black silk gown and cream lace ruffles – with far more detail than her encounter with the prince. She hardly spoke to him at all. Too shy to approach her directly, the prince had instead approached her older sister Caroline, stumbling out unaccustomed praises of her beauty and charm.

George was not the only man to find Sarah Lennox mesmerisingly attractive. It was hard to pin down the exact nature of her appeal, which was not always apparent at first sight. Her sisters failed to understand it at all. ‘To my taste,’ wrote Emily, ‘Sarah is merely a pretty, lively looking girl and that is all. She has not one good feature … her face is so little and squeezed, which never turns out pretty.’120 (#litres_trial_promo) Her brother-in-law Henry Fox thought otherwise. ‘Her beauty is not easily described,’ he wrote, ‘otherwise than by saying that she had the finest complexion, the most beautiful hair, and prettiest person that was ever seen, with a sprightly and fine air, a pretty mouth, remarkably fine teeth, and an excess of bloom in her cheeks, little eyes – but that is not describing her, for her great beauty was a peculiarity of countenance that made her at the same time different from and prettier than any other girl I ever saw.’121 (#litres_trial_promo) Horace Walpole saw her once as she acted in amateur theatricals at Holland House; his detached connoisseur’s eye caught something of her intense erotic promise: ‘When Lady Sarah was all in white, with her hair about her ears and on the ground, no Magdalen by Caravaggio was half so lovely and expressive.’122 (#litres_trial_promo) Sarah, unfazed by the comparison to a fallen woman, declared its author ‘charming’. She liked Walpole, she said with disarming honesty, because he liked her.

This cheerful willingness to find good in all those who found good in her no doubt smoothed her encounters with the awkward Prince of Wales. They met at formal Drawing Rooms and private balls, and George’s attention was so marked that it was soon noticed by the sharp-eyed Henry Fox. At this point, he did not take it seriously; it was no more than an opportunity for a good tease. ‘Mr Fox says [George] is in love with me, and diverts himself extremely,’ Sarah told Emily wryly.123 (#litres_trial_promo)

Bute, however, knew that George’s feelings were anything but a joke. Having declared them to his mentor, George was now desperate to know whether Sarah Lennox could be considered a suitable candidate for marriage. It seems never to have occurred to him that this was a decision he might make for himself. He submitted himself absolutely to Bute’s judgement, assuring him that no matter what the earl concluded, he would abide by his decision. He hoped for a favourable answer, but insisted that their relationship would not be affected if it were not so: ‘If I must either lose my friend or my love, I shall give up the latter, for I esteem your friendship above all earthly joy.’124 (#litres_trial_promo) The rational part of him must have known what Bute’s answer would be. It was inconceivable that he should marry anyone but a Protestant foreign princess; an alliance between the royal house and an English aristocratic family would overthrow the complex balance of political power on which the mechanics of the constitutional settlement depended.

To marry into a family that included Henry Fox was, if possible, even more outrageously improbable. Henry was the brother of Stephen Fox, the lover of Lord Hervey, the laconic Ste, who had been driven into a jealous fury by the ambiguous relationship between Hervey and Prince Frederick. Henry Fox was one of the most controversial politicians of his day: able, amoral and considered spectacularly corrupt, even by the relaxed standards of eighteenth-century governmental probity. A man described by the Corporation of the City of London as a ‘public defaulter of unaccounted millions’ was unlikely to prove a suitable brother-in-law to the heir to the throne. Bute’s judgement was therefore as unsurprising as it was uncompromising: ‘God knows, my dear sir, I with the utmost grief tell it you, the case admits of not the smallest doubt.’ He urged George to consider ‘who you are, what is your birthright, what you wish to be’. If he examined his heart, he would understand why the thing he hoped for could never happen. The prince declared himself reluctantly persuaded that Bute was right. ‘I have now more obligations to him than ever; he has thoroughly convinced me of the impossibility of ever marrying a countrywoman.’ He had been recalled to a proper sense of duty. ‘The interest of my country shall ever be my first care, my own inclinations shall ever submit to it; I am born for the happiness or misery of a great nation, and consequently must often act contrary to my passions.’125 (#litres_trial_promo)

George’s renunciation was made easier by the fact that he did not see the object of his passion for some months. The next time he did so, he was no longer Prince of Wales but king. George II died in October 1760; Sarah Lennox went to court in 1761, when all the talk was of the impending coronation. As soon as he saw her again, all George’s hard-won resolution ebbed away, as ‘the boiling youth’ in him made him forget all the promises he had made to Bute. Despite his undertaking to give her up, he took the unprecedented step of declaring to her best friend the unchanged nature of his feelings for Sarah. One night at court, he cornered Lady Susan Fox-Strangways, another member of the extensive Fox clan. The conversation that followed was so extraordinary that Lady Susan repeated it to Henry Fox, who transcribed it. The king asked Lady Susan if she would not like to see a coronation. She replied that she would.

K: Won’t it be a finer sight when there is a queen?

LS: To be sure, sir.

K: I have had a great many applications from abroad, but I don’t like them. I have had none at home. I should like that better.

LS: (Nothing, frightened)

K: What do you think of your friend? You know who I mean; don’t you think her fittest?

LS: Think, sir?

K: I think none so fit.

Fox then said that George ‘went across the room to Lady Sarah, and bid her ask her friend what he had been saying and make her tell her all’.126 (#litres_trial_promo)

The fifteen-year-old Sarah, never very impressed by George’s attentions, had been conducting a freelance flirtation of her own, which had just come to an end, and she was in no mood to be polite to other suitors, even royal ones. When George approached her at court soon after, she rebuffed all his attempts to discuss the conversation he had had with Lady Susan. When he asked whether she had spoken to her friend, she replied monosyllabically that she had. Did she approve of what she had heard? Fox reported that ‘She made no answer, but looked as cross as she could. HM affronted, left her, seemed confused, and left the Drawing Room.’127 (#litres_trial_promo)

Fox worked away, trying to discover the true state of George’s feelings for Lady Sarah. Despite the unfortunate snub, they seemed to Fox as strong as ever. He was less certain, however, of where they might lead. Fox told his wife that he was not sure whether George really intended to marry her, adding that ‘whether Lady Sarah shall be told of what I am sure of, I leave to the reader’s discretion’.128 (#litres_trial_promo) If a crown was out of the question, it might be worth Sarah settling for the role of royal mistress. At the Birthday Ball a few months later, Fox’s hopes of the ultimate prize revived once more. ‘He had no eyes but for her, and hardly talked to anyone else … all eyes were fixed on them, and the next morning all tongues observing on the particularity of his behaviour.’129 (#litres_trial_promo) But after over a year of encouraging signals, there was still no sign of any meaningful declaration from the king. Determined to bring matters to a head, Lady Sarah was sent back to court with very precise instructions to do all she could to extract from her vague suitor some concrete sense of his intentions. As she explained to Lady Susan, Fox had coached her to perfection: ‘I must pluck up my spirits, and if I am asked if I have thought of … or if I approve of … I am to look him in the face and with an earnest but good-humoured countenance, say “that I don’t know what I ought to think”. If the meaning is explained, I must say “that I can hardly believe it” and so forth.’ It was all very demanding. ‘In short, I must show I wish it to be explained, without seeming to suggest any other meaning; what a task it is. God send that I may be enabled to go through with it. I am allowed to mutter a little, provided that the words astonished, surprised, understand and meaning are heard.’130 (#litres_trial_promo)