По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

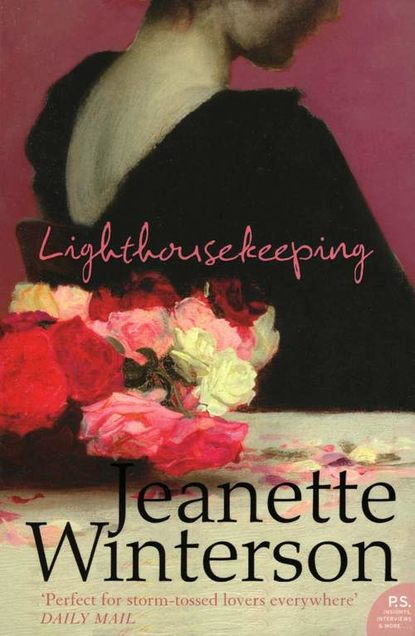

Lighthousekeeping

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My mother had gone. The rope was idling against the rock. I pulled it towards me over my arm, shouting, ‘Mummy! Mummy!’

The rope came faster and faster, burning the top of my wrist as I coiled it next to me. Then the double buckle came. Then the harness. She had undone the harness to save me.

Ten years before I had pitched through space to find the channel of her body and come to earth. Now she had pitched through her own space, and I couldn’t follow her.

She was gone.

Salts has its own customs. When it was discovered that my mother was dead and I was alone, there was talk of what to do with me. I had no relatives and no father. I had no money left to me, and nothing to call my own but a sideways house and a skew-legged dog.

It was agreed by vote that the schoolteacher, Miss Pinch, would take charge of matters. She was used to dealing with children.

On my first dismal day by myself, Miss Pinch went with me to collect my things from the house. There wasn’t much – mainly dog bowls and dog biscuits and a Collins World Atlas. I wanted to take some of my mother’s things too, but Miss Pinch thought it unwise, though she did not say why it was unwise, or why being wise would make anything better. Then she locked the door behind us, and dropped the key into her coffin-shaped handbag.

‘It will be returned to you when you are twenty-one,’ she said. She always spoke like an Insurance Policy.

‘Where am I going to live until then?’

‘I shall make enquiries,’ said Miss Pinch. ‘You may spend tonight with me at Railings Row.’

Railings Row was a terrace of houses set back from the road. They reared up, black-bricked and salt-stained, their paint peeling, their brass green. They had once been the houses of prosperous tradesmen, but it was a long time since anybody had prospered in Salts, and now all the houses were boarded up.

Miss Pinch’s house was boarded up too, because she said she didn’t want to attract burglars.

She dragged open the rain-soaked marine-ply that was hinged over the front door, and undid the triple locks that secured the main door. Then she let us in to a gloomy hallway, and bolted and barred the door behind her.

We went into her kitchen, and without asking me if I wanted to eat, she put a plate of pickled herrings in front of me, while she fried herself an egg. We ate in complete silence.

‘Sleep here,’ she said, when the meal was done. She placed two kitchen chairs end to end, with a cushion on one of them. Then she got an eiderdown out of the cupboard – one of those eiderdowns that have more feathers on the outside than on the inside, and one of those eiderdowns that were only stuffed with one duck. This one had the whole duck in there I think, judging from the lumps.

So I lay down under the duck feathers and duck feet and duck bill and glassy duck eyes and snooked duck tail, and waited for daylight.

We are lucky, even the worst of us, because daylight comes.

The only thing for it was to advertise.

Miss Pinch wrote out all my details on a big piece of paper, and put it up on the Parish notice board. I was free to any caring owner, whose good credentials would be carefully vetted by the Parish Council.

I went to read the notice. It was raining, and there was nobody about. There was nothing on the notice about my dog, so I wrote a description of my own, and pinned it underneath:

ONE DOG. BROWN AND WHITE ROUGH COATED TERRIER. FRONT LEGS 8 INCHES LONG. BACK LEGS 6 INCHES LONG. CANNOT BE SEPARATED.

Then I worried in case a person might mistake it was the dog’s legs that could not be separated, instead of him and me.

‘You can’t force that dog on anybody,’ said Miss Pinch, standing behind me, her long body folded like an umbrella.

‘He’s my dog,’

‘Yes, but whose are you? That we don’t know, and not everybody likes dogs.’

Miss Pinch was a direct descendent of the Reverend Dark. There were two Darks – the one who lived here, that was the Reverend, and the one who would rather be dead than live here, that was his father. Here you meet the first one, and the second one will come along in a minute.

Reverend Dark was the most famous person ever to come out of Salts. In 1859, a hundred years before I was born, Charles Darwin published his Origin of Species, and came to Salts to visit Dark. It was a long story, and like most of the stories in the world, never finished. There was an ending – there always is – but the story went on past the ending – it always does.

I suppose the story starts in 1814, when the Northern Lighthouse Board was given authority by an Act of Parliament to ‘erect and maintain such additional lighthouses upon such parts of the coast and islands of Scotland as they shall deem necessary’.

At the north-western tip of the Scottish mainland is a wild, empty place, called in Gaelic Am Parbh – the Turning Point. What it turns towards, or away from, is unclear, or perhaps it is many things, including a man’s destiny.

The Pentland Firth meets the Minch, and the Isle of Lewis can be seen to the west, the Orkneys to the east, but northwards there is only the Atlantic Ocean. I say only, but what does that mean? Many things, including a man’s destiny.

The story begins now – or perhaps it begins in 1802 when a terrible shipwreck lobbed men like shuttlecocks into the sea. For a while, they floated cork up, their heads just visible above the water line, but soon they sank bloated like cork, their rich cargo as useless to life as their prayers.

The sun came up the next day and shone on the wreck of the ship.

England was a maritime nation, and powerful business interests in London, Liverpool and Bristol demanded that a lighthouse be built here. But the cost and the scale were enormous. To protect the Turning Point, a light needed to be built at Cape Wrath.

Cape Wrath. Position on the nautical chart, 58° 37.5° N, 5°W.

Look at it – the headland is 368 feet high, wild, grand, impossible. Home to gulls and dreams.

There was a man called Josiah Dark – here he is – a Bristol merchant of money and fame. Dark was a small, active, peppery man, who had never visited Salts in his life, and on the day that he did he vowed never to return. He preferred the coffee-houses and conversation of easy, wealthy Bristol. But Salts was the place that would provide the food and the fuel for the lighthousekeeper and his family, and Salts would have to provide the labour to build it.

So with much complaining and more reluctance, Dark bedded for a week at the only inn, The Razorbill.

It was an uncomfortable place; the wind screeched at the windows, a hammock was half the price of a bed, and a bed was twice the price of a good night’s sleep. The food was mountain mutton that tasted like fencing, or hen tough as a carpet, that came flying in, all a-squawk behind the cook, who smartly broke its neck.

Every morning Josiah drank his beer, for they had no coffee in this wild place, and then he wrapped himself tight as a secret, and went up onto Cape Wrath.

Kittiwakes, guillemots, fulmars and puffins covered the headland, and the Clo Mor cliffs beyond. He thought of his ship, the proud vessel sinking under the black sea, and he remembered again that he had no heir. He and his wife had produced no children and the doctors regretted they never would. But he longed for a son, as he had once longed to be rich. Why was money worth everything when you had none of it, and nothing when you had too much?

So, the story begins in 1802, or does it really begin in 1789, when a young man, as fiery as he was small, smuggled muskets across the Bristol Channel to Lundy Island, where supporters of the Revolution in France could collect them.

He had believed in it all, somewhere he did still, but his idealism had made him rich, which was not what he intended. He had intended to escape to France with his mistress and live in the new free republic. They would be rich because everyone in France was going to be rich.

When the slaughtering started, he was sickened. He was not timid of war, but the tall talk and the high hearts had not been for this, this roaring sea of blood.

To escape his own feelings, he joined a ship bound for the West Indies and returned with a 10% share in the treasure. After that, everything he did increased his wealth.

Now he had the best house in Bristol and a lovely wife and no children.

As he stood still as a stone pillar, an immense black gull landed on his shoulder, its feet gripping his wool coat. The man dared not move. He thought, wildly, that the bird would carry him off like the legend of the eagle and child. Suddenly, the bird spread its huge wings and flew straight out over the sea, its feet pointed behind it.

When the man got to the inn, he was very quiet at his dinner, so much so that the wife of the establishment began to question him. He told her about the bird, and she said to him, ‘The bird is an omen. You must build your lighthouse here as other men would build a church.’

But first there was the Act of Parliament to be got, then his wife died, then he took sail for two years to repair his heart, then he met a young woman and loved her, and so much time passed that it was twenty-six years before the stones were laid and done.

The lighthouse was completed in 1828, the same year as Josiah Dark’s second wife gave birth to their first child.

Well, to tell you the truth, it was the same day.