По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

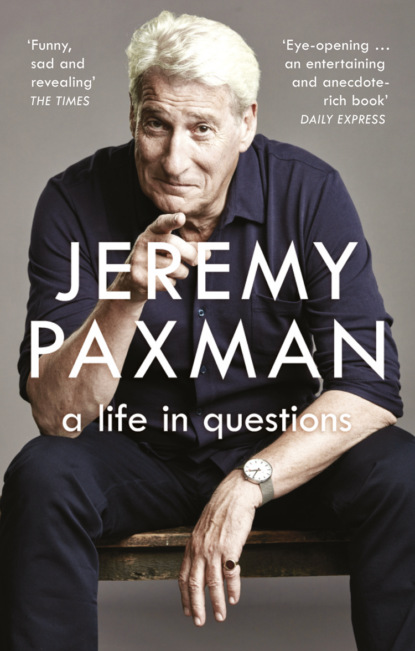

A Life in Questions

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The sole women in this odd world were the headmaster’s long-suffering little wife and the school matron, a thin, beaky figure who bustled about the place in dark-blue uniform and starched nurse’s cap, dispensing ‘malt’ to boys who weren’t growing quickly enough, ‘tonic’ to boys who were growing too fast, and laxatives to anyone who hesitated in answering her questions about their bowel movements. Since the lavatories were housed in an outbuilding which regularly froze up in winter, daily bowel movements were low on the list of priorities. Matron also supervised the compulsory once-a-week bath.

Why did our parents surrender us to the care of such a bizarre institution? The short – and correct – answer is that they thought they were buying us a head-start in life. Neither Paul nor Gerald, my friends at home, seemed to be especially disadvantaged by being spared the experience – though it was hard to tell when we were playing war games or cooking bannocks on the ovens we made in the woods out of old bricks and a sheet of corrugated iron.

Slowly but surely, though, the chasm widened. There were new friends among the fellow inmates of the Lickey Hills Preparatory School, and they were the sons of doctors and architects. Which, I suppose, was one of the things my family was paying for. British class divisions were much deeper then (though the subject is still endlessly written about in newspapers and magazines, as if nothing has changed). The truth is that, for those who can afford it, education has been for generations a way of translating the children of one class into the adolescents of another. The parents made things and generated wealth. Their children emerged from education for careers in the professions. On the way, they have been hived off from the mainstream. Few of us ever recover. The obvious solution is to make the education provided by the state so good that no one but a lunatic would want to go elsewhere.

My parents’ pockets weren’t deep enough for me to feel entirely at ease with the boys who genuinely belonged to the professional classes. One day, at my friend Philip Kelly’s house, I saw the milk delivery. It included yoghurt, a substance which had never darkened the door of High Lea – or 262 Old Birmingham Road, as it was less portentously known – and of which I had indeed never heard. Phil’s father was an architect. My own father’s sally into sophistication was to bring home an avocado pear one day. We were all rather baffled by it.

Life at High Lea had a predictable routine. In the morning, after a teaspoonful of cod-liver oil followed by another of viscous orange-juice concentrate – both of them provided, I think, by the National Health Service – my brothers and I set off in our grey shorts, blue Aertex shirts, navy blazers and caps to walk the mile to school. Occasionally we were waylaid by other boys, notably the son of the local butcher, who once boasted to us that he could hold a piece of liver in his hand for longer than any of us could imagine. Sometimes the encounters got physical and we had to run for it. On the way home in the evening we might stop by the post office to see if we could extract any forgotten coins by pressing button B in the telephone box, money we would then spend on sweets – the penny chew was particularly popular.

The sixty or so boys in the school ate together in one great dining room. There was tea from an enormous urn, at break there was a small bottle of milk (again provided, I think, by the state) and chunks of bread coated in beef dripping – delicious when heavily sprinkled with salt. Lunch was generally a stew or some variety of shrivelled offal – liver or kidneys or whatever was cheap that week, I suppose. The evening meal was usually something like tinned pilchards in tomato sauce, washed down with soapy-tasting tea from The Urn.

For the last year or so of my time at prep school I was expected to live in as a boarder, the final enrolment into the repressed self-reliance of what the middle classes took to be ‘a decent education’. We slept in dormitories of four or five beds apiece, in which the only visible contact with home was the rug we had each been given by our mothers. Mine was in some odd artificial fibre, striped in yellow, grey and white – testament to the family’s unfamiliarity with boarding-school life: everyone else had some species of woollen tartan, sometimes claiming it to be that of the family clan. Sunday mornings were spent writing letters home. This was done under the eye of a member of staff, and followed a strict formula:

Dear mother and father,

How are you? I am well.

The first eleven played Abberley yesterday. We lost five–nil.

After that, it was a desperate struggle to creep over onto the back of the piece of paper, as we knew that a letter that was too short would be rejected by the supervising teacher.

Looking back on it, the life we were leading was so utterly separate from our home lives that it was a wonder we found any point of contact at all. A stranger glancing in through the big Victorian window might have guessed that the adult was there to censor what was being written. And indeed, sometimes he did: my brother Giles, who was having an absolutely wretched time, several times wrote letters reading ‘I hate it here, please come and take me home,’ which were torn up. He managed to smuggle a couple of notes out in the pockets of day boys at the school, but our parents thought he was making a fuss about nothing, and would eventually settle down. When he finally ran away and barricaded himself in his bedroom at home they returned him to the school: it was important to them that you did your duty, and ‘putting up with things’ was part of that.

By the standards of the time, I suppose the Lickey Hills Preparatory School was no worse than many others. If there were school inspectors in those days, we were unaware of them, and it seemed that anyone could open a school whenever and wherever they liked. At least we had little trouble of the kind which befell a friend enduring a similar education elsewhere. When he eventually plucked up the courage to go to the headmaster to report that the geography master kept putting his hand up his shorts, the head replied with a long-suffering air that ‘Mr Jones is what we call a homosexual. Do you know what that means? No? It means he prefers little boys to little girls. You will find that many of the staff are homosexuals. Frankly, on the money I pay them, they’re the only people I can get to work here.’

The language betrays the lazy prejudices of the time. As far as I was aware, we had no trouble with paedophiles at Lickey Hills, though one or two of the masters did seem to take a keen interest in supervising communal showers and suddenly switching the water from warm to freezing. In the popular cliché, the prep and public schools of the fifties and early sixties were alive with depraved behaviour. All I can say is that in the whole of my school career I never came across a single paedophile teacher, and very few boys with a taste for much more than the solitary vice.

Lickey Hills was a business, and, it seemed, a not very successful one. Shortage of money was a fact of life at every level. Because the school could not afford a physics laboratory, the elderly science master was reduced to describing the outcome of experiments by drawing the usual results on a blackboard. Since we had to imagine that the line of chalk was a piece of metal, we were not left much the wiser about its powers of conductivity. But if the school was poor, the teachers were much poorer. Colonel Collinson seemed the only one who had any form of car – a Messerschmitt three-wheeler in a shade of paraffin pink. When he had lifted the roof and eased his great frame and moustachioed face behind the steering bar he looked like some crazy life-sized children’s toy.

Apart from having a missing finger, Colonel Collinson must also have been bit deaf. One morning while we were at breakfast there was an explosion from the staff area.

‘Colonel Collinson, I have asked you three times to pass my wife the marmalade!’ roared the headmaster.

The Colonel mumbled some explanation.

‘Colonel Collinson,’ barked the head, ‘you are dismissed!’

There was no going back from such a public sacking, and the Colonel’s imminent departure was the only topic of conversation among us in the twenty minutes between the end of breakfast and the first lesson of the day. I cannot now recall who came up with the evil idea which ensured the poor man’s final humbling. It required several of us to carry it out, so perhaps it was just one of those things that emerges naturally and collectively. By applying all our strength first to one side of the Messerschmitt bubble car and then to the other, we levered it off the ground, grabbed a few bricks and lowered it back, so that all three wheels were just clear of the surface. A few minutes into the lesson we looked out of the window and saw the Colonel descending the school steps, wearing a British Warm officer’s greatcoat and carrying a small brown leather suitcase, which presumably contained all his worldly goods. We watched as the poor man strode to his car, opened the Perspex bubble, tossed his battered suitcase into the back, and started the engine. The wheels spun, but nothing moved. His humiliation was complete.

For schools like Lickey Hills to work their alchemy, there had to be as great a disengagement from the outside world as possible. (‘What do you expect of the parents?’ one of those paying the bill for this transformation asked my next headmaster. ‘Pay the fees and stay away!’ he replied succinctly.) Fathers generally seem to have understood this better than mothers. The son of a distinguished lawyer recalled a particular low point when he was gathered with his fellow inmates at the end of term, awaiting the arrival of his father to collect him for the holidays. He watched as his father strode into the room, grabbed another child and dragged him protesting to the car, saying, ‘Oh, do come on, Stephen.’ It was only as he was about to drive off, and the small boy managed to attract his attention by exclaiming, ‘But sir, I’m not your son!’ that the father turned, and with a cry of ‘Oh no, you’re not!’ realised his mistake.

‘Teddy boys’, with their long jackets and quiffed hairstyles, were a 1950s phenomenon. Not at Lickey Hills School – or ‘Hillscourt’, as it had by then been renamed by its bonkers proprietor and headmaster – they weren’t. Well into the 1960s they were blamed for anything that went wrong in the school grounds. On one occasion I watched the headmaster’s son chucking lighted matches into gorse bushes, and duly setting the hills alight – when the fire brigade arrived he explained that the inferno was the work of the teds, who were blamed for just about everything that went wrong at the school (apart from the hit-and-miss teaching.) Periodically, the teds clambered over a fence and vandalised the wooden huts at the end of the swimming pool. This was a concrete-lined hole in the ground, fed by a stream from the hills and replete with frogs and newts. ‘Learning to swim’ involved being dropped into the pool and trying to reach the other side before death by drowning or exposure.

The headmaster became obsessed with preventing the teds from sharing this luxury. One Sunday afternoon he decided it was time to act. Fifteen or so of the more senior boys (all aged twelve or thirteen, therefore) were summoned to his study, where, we discovered, he had amassed an arsenal that would have equipped a minor peasants’ revolt. Stacked in the corner were scythes, sickles, chisels, hammers, an air rifle and a shotgun.

‘Boys,’ he said, ‘if the teds break in this afternoon, you’re to deal with them.’

Since we knew that the local youths were all fifteen, sixteen or older, we were terrified. But we had weaponry and they, we hoped, did not. The headmaster was halfway through his pre-battle briefing when a small boy knocked on the door and entered the room, exclaiming breathlessly, ‘Sir, the teds have broken into the swimming pool!’ ‘Get them, boys!’ barked the head. The most eager sprinted for the pool. The rest of us followed at the pace of Russian conscripts being thrown into an assault at Stalingrad. Only when we reached the hole in the ground did we realise that we had left the scythes, knives and guns in the headmaster’s study.

By the time we reached the pool, the teds were clambering back over the wooden fence separating the school grounds from the local park. With a great feeling of relief we paused our mission, until in the distance we heard the headmaster bellowing that we were to bring the culprits to justice. With sinking hearts we climbed the fence and followed them into the park. The teds jogged on nonchalantly, turning occasionally to shout obscenities at the posse of much smaller boys pursuing them. Then, to our horror, they stopped and stood their ground. Two or three of them tore planks of wood from the park fence, and brandished them like clubs.

The gang leader beckoned, saying, ‘OK. One of us, and one of you.’

Jeremy Clewer, the son of a Quaker family, was one of the quietest and kindest boys in the school. He also had the misfortune to be one of the tallest.

‘You,’ said the ted, pointing at Clewer. ‘You fight.’

Clewer looked out from under his floppy fringe. This was definitely not the way the Society of Friends usually dealt with things. The head ted stepped forward and punched him. Clewer fell to the ground, and the two of them rolled around in the dust for a few minutes. The battle of champions ended inconclusively. One of the other members of the gang pointed at the identical woollen jumpers we all wore – hoops of dark and light blue – and said, ‘What is that place then, some sort of approved school?’

The two combatants brushed the dust from their clothes, and the gang sauntered on their way while we gathered around Clewer and told him how brave he’d been, before heading back to describe the battle to the headmaster. He exploded, grabbed the telephone and shouted at the Duty Sergeant in the local police station, threatening him with the Chief Constable and demanding he set off immediately to arrest the teds. An hour later the Sergeant appeared outside the school with half a dozen sheepish teenage boys, and explained that he wasn’t sure there was much he could do. The headmaster took this as confirmation that the world truly was going to hell in a handcart.

© Geoff Thompson

2

Didn’t You Hear the Bell? (#u68cf631f-bd42-5296-a021-92a97315e6e0)

As their name suggests, ‘preparatory schools’ like Lickey Hills were supposed to prepare you for an adolescence to be spent at an independent secondary school. My parents had chosen Malvern College, founded by a group of Midlands businessmen in 1865, at the height of the mid-Victorian belief in educational alchemy. Malvern was an early-nineteenth-century spa town in Worcestershire, and the great stone mock-Gothic buildings testified to the school’s ambitions. It had never escaped the Second Division (but then, the First Division was really only Eton, Winchester, Westminster, and sometimes, when the wind was blowing in the right direction, Harrow). It was, though, unquestionably one of the better schools in the Second Division, aping the grander institutions while jealously preserving its own unimaginative slang as if it were Holy Writ. All new boys were examined on their familiarity with this stupid vernacular (‘wagger’ for wastepaper basket, ‘Shaggers’ for Shakespeare, ‘ducker’ for swimming pool, etc., etc.) to determine whether they were fit to enter the school community. You were also expected to know the nicknames for each of the sixty-odd members of staff – all but one of them Oxbridge products.

The school’s expansive grounds lay in the lee of the Malvern Hills, replete with a beautifully situated cricket pitch, an enormous stone-clad chapel and a library intended as a memorial to the hundreds of pupils who had died in the First World War. The six hundred teenage boys slept and ate in a series of ten rambling Victorian houses scattered about the grounds, each run by a separate housemaster. Every house had a distinct reputation: boys in Number Eight house were all sex maniacs, those in Number Seven unnaturally athletic, and those in Number Three compulsorily gay. Most of the classrooms were housed in the three-sided neo-Gothic main building, which surrounded a courtyard dominated by a statue of St George, though science lessons tended to be held in a purpose-built modern block beyond the Memorial Library. There was an elaborate cricket pavilion, fives, squash and racket courts, a purpose-built gym, which also housed a shop selling jockstraps and thick woollen games shorts, and a grim swimming-pool building where we were made to practise rescuing victims of drowning while fully dressed. In the tuckshop (‘the Grub’) Mr Davies, a short, grey-haired Welshman in a white overall, dispensed tea and cheese-and-pickle rolls all day. There were many obscure rules about how many buttons on your jacket you were allowed to have undone at various levels of seniority in the school.

That sort of pettifogging tyranny – another unwritten rule specified the grade of seniority necessary to be permitted to have one hand or two in your trouser pockets – was deemed vital if the school was to achieve its goal of transforming the children of successful Midlands manufacturers into something approximating to gentlemen. I hated the place, though I have to admit that it was very effective in taking boys whose parents had made things or provided services, and turning them into the sort of chaps who would be decent District Officers somewhere in the fast-vanishing Empire, or members of some profession or another. There was much sport, a compulsory afternoon each week in the Combined Cadet Corps, for which we were required to dress up in army, navy or air force uniform (I chose the navy, on the grounds that Malvern is getting on for being as far from the sea as is possible in England), and straw boaters were worn when leaving the school grounds. Our uniform was pinstripe trousers, black jackets, and detachable stiff collars on Sunday. We looked like spotty clerks scurrying to our ledgers in a Victorian counting house, apart from the school prefects, who wore tailcoats, carried silver-topped black canes and affected an ascendancy swagger.

C.S. Lewis had lasted a year as a pupil at the school before the First World War, and described the place (not affectionately) in his account of the spiritual journey he made from atheism to Christianity, Surprised by Joy. ‘Wyvern’, he recounts, was essentially run by the senior boys, or ‘Bloods’, and characterised by homosexuality, of which, for his time, he took a rather tolerant view. He thought it the least spontaneous, least boyish society he had ever known, in which ‘everything was calculated to the great end of advancement. For this games were played; for this clothes, friends, amusements and vices were chosen.’

Unlike the works of old boys who had become generals or county cricketers, Lewis’s memoir was constantly being banned from the school library, which only made it all the more alluring. The school had obviously improved a bit since Lewis’s day, but the influence of the Bloods – sporty oafs happiest on the games field – was still profound. When I recall these days, I am astonished that they occurred in my lifetime. Can it really be true that only fifty years ago junior boys were expected to act as ‘fags’ – effectively slaves – to senior boys, and that the eighteen-year-old who had been appointed head of house had the formal right – frequently exercised – to beat boys? I had been beaten by the headmaster of my prep school. Now I was beaten by his son.

The ritual on these occasions was always the same. A few minutes after lights-out at 10.30, the junior prefect would be sent to fetch you from the dormitory where we slept in groups of around a dozen. The form of words was unchanging.

‘Put on your dressing gown and come with me downstairs.’

You followed this much larger figure down the cold, dark stairwell and along the corridor to the prefects’ common room, where ten or so other eighteen-year-olds sat in a circle, with a single chair in the middle. You were told to stand inside the circle.

‘Why did you refuse to get into bed when you were told to do so by Robinson [the prefect on dormitory patrol that night]?’ demanded the head of house.

‘Because I didn’t want to.’

‘But you had been told to do so.’ He spoke with all the authority of an army subaltern, which within a month or so he might have become.

‘But I don’t respect Robinson,’ I replied.

‘The purpose of a public-school education, Paxman, is to teach you to respect people you don’t respect. Take off your dressing gown and bend over the chair.’

It hurt like hell.

The post-match analysis after these beatings was always the same. You went back to your bed under cover of darkness, trying not to reveal that you were crying. The whole of the rest of the dormitory was lying awake in the darkness, of course. Finally, a voice would whisper, ‘How many did you get?’

And then the bragging began. It hadn’t hurt much.