По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

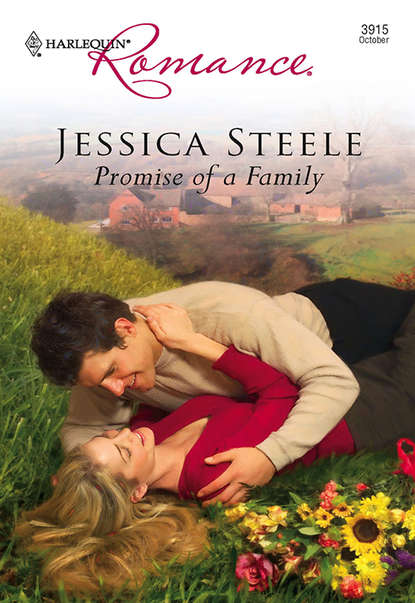

Promise Of A Family

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It heartened Leyne that her sister fully intended to tell her offspring of her father. But Leyne knew that she could not leave it there. ‘Pip wants to know now, Mum,’ she said, and insisted, ‘I think she’s old enough now.’

‘She’ll forget all about it soon. It’s only a whim,’ Catherine reasoned.

‘She’s been wanting to know for some while now.’

‘It will pass.’

Leyne did not want to badger her mother, who was already starting to show prickles in her protectiveness of her eldest daughter. ‘I don’t think she will,’ she pressed on. And, knowing her mother had lived in the same house until after Pip had celebrated her seventh birthday, ‘As tractable as Pip is, you know what she’s like once she has set her mind to something.’

Catherine Webb looked exasperated and worried all at the same time. ‘Maxine will want to tell her herself.’

‘Max isn’t here,’ Leyne reminded her mother quietly. ‘I’ve tried countless times to contact her, but her phone isn’t ringing out. And while I have an emergency number for—’

‘I wouldn’t call this an emergency!’ her mother cut in hurriedly. ‘Pip will just have to wait.’

Love her mother though she did, Leyne felt very much like telling her that she was not the one who was guardian to the child; she was not the one who would look up occasionally from whatever she was doing to find Pip looking at her as though she was just bursting to ask how far she had got along with her enquiries.

‘I don’t think it will wait, Mum,’ she stated seriously. ‘I’m worried that it’s preying on Pip’s mind.’ Leyne broke off to try another tack. ‘You must have met her father?’

‘No,’ her mother promptly replied. ‘I never met him.’

Which, since she had always known her parent to be incapable of telling a lie, was something of a body-blow to Leyne. ‘You never—?’ She broke off, something in her mother’s expression seeming to tell her that her mother knew more than she was telling. ‘But you do know who he is?’ she pressed.

Her mother gave her cross look, but did concede, ‘He never came into the house. And it was only a brief affair—over almost before it began.’

‘But it was long enough for Max to fall in love with him?’

Catherine Webb’s expression softened. ‘Oh, yes,’ she said. ‘She loved him.’ A faraway look was in her eyes. ‘Then Maxine came home one night and shut herself in her room. When the next morning I asked her what was wrong—it was obvious she had been crying—she said she wouldn’t be seeing him again. Nor did she. In fact she refused to so much as mention his name ever again.’

‘You know his name, though?’

Her mother sighed and, after a silent tussle with herself, finally gave in. ‘His name is John Dangerfield.’

John Dangerfield. Leyne rolled the name around in her head. But she knew she had never heard of him. ‘Can you tell me anything more about him?’

‘I know very little about him. As I said, I never met him. He rarely came to the house, and the few times he did Maxine would be on the lookout for his car and would dash out to him. Though…’ Her mother hesitated, but only for a moment or two, and then stated, ‘I expect you to use the information judiciously, Leyne. Pip is at a very vulnerable age.’

‘I know it. It’s why I am being very careful here. Anything you tell me I’ll treat with the utmost care,’ Leyne promised. ‘But we have to bear in mind that Pip is likely to grow more and more anxious if I just try to fob her off. And you know yourself how her asthma can be triggered when she gets emotionally upset. I want to avoid anything that might bring on an attack.’

Catherine looked out of the window to where Pip was now seated on a wooden garden bench, quietly talking to Suzie. ‘Poor scrap,’ she said softly of her granddaughter, and confessed, ‘I really don’t know much more than his name, but, in all fairness, I suppose I must allow she has every right to know. John Dangerfield,’ she revealed, ‘is the chairman of a company called J. Dangerfield, Engineers.’

J. Dangerfield, Engineers? Leyne did not know the company, but the company name prodded a tiny wisp of memory—as if she had heard or read something about them recently.

‘Before you go charging in to tell Pip what I’ve told you,’ her mother cautioned, ‘I think it might be an idea to contact him first.’

‘I wasn’t thinking of contacting him at all!’

‘Then I think you should.’ And at Leyne’s look of enquiry. ‘An utter darling though Pip is most of the time, you know how intransigent she can be on the odd occasion.’

‘That’s true enough,’ Leyne had to admit.

And her mother went on, ‘If I know anything at all about my granddaughter, she is not going to want to leave it there.’

‘Ah…’ Leyne murmured. ‘You…Oh, grief—you think she’ll actually want to meet him?’

‘Wouldn’t you?’

Leyne thought about it, and had to acknowledge that she would not want to leave it at just knowing his name. Weakly, realising that she was taking on more than she possibly should, she was very tempted to leave matters until Max returned home. Leyne then made the mistake of glancing out of the window to where Pip was now looking back at her—with that direct kind of look on her face. And Leyne knew then that whatever it took to bring that little girl peace of mind she would do it. ‘You’re right, of course,’ she admitted.

‘Then I suggest you contact him first before you tell her who he is.’

‘Oh, I don’t—’

‘Do it, Leyne!’ her parent instructed sternly. ‘Most definitely do it!’

‘Why definitely?’ she asked, unable to see why she should involve Pip’s father at this stage.

‘Because,’ her mother replied firmly, ‘for all we know he might want to deny paternity. He’s never paid a penny towards Pip’s upkeep after all. Not that Maxine would ever ask for his support; she’s much too proud for that,’ Catherine said with dignity, and Leyne did not have to wonder from where her sister, herself too for that matter, had inherited that pride.

She and Pip were on their way back to their home in Surrey when Leyne was again made to realise that Pip was every bit as bright as she had always thought. ‘You and Nanna were having a good chat,’ she remarked. ‘Was it about me?’ she asked, in her forthright manner.

Leyne saw no reason to lie to her. ‘I thought Nanna might be able to tell me something about your father, and—’

‘Did she?’ Pip asked eagerly. ‘Was—?’

‘Oh, love, try to be patient. I know it’s difficult for you, but it may take quite some while.’

Leyne hated not to be able to tell her what she had learned that day. And, had her mother not insisted she contact the chairman of J. Dangerfield, Engineers, before she acquainted Pip with her father’s name, Leyne might well have said more. But, on thinking about it, Leyne knew that her mother was right and that her niece would not want to leave it there. She would fidget and fidget at it and would not rest until she had met him. Leyne blamed herself that she had not thought it that far through. Pip could be a dogged little miss when she set her mind on anything. And what was more important to her than knowing—and meeting—her father?

Leyne faced then that, having willingly volunteered to act as Pip’s guardian, the task, up until Pip had asked that one important question, had been no task at all. But in her mother’s absence she was the dear child’s guardian, and therefore it was up to her, and no one else, to make whatever decisions were necessary in regard to the child’s welfare. Decisions, no matter how difficult, which were not to be shirked.

With the company name J. Dangerfield, Engineers, to the forefront of her mind, and a certainty growing in her head that she had heard or read some snippet about that firm recently, Leyne had to wait until Pip was in bed before she could take any action.

As luck would have it, there were almost a week’s newspapers awaiting collection for recycling.

After scouring three newspapers, Leyne was beginning to believe her memory for things inconsequential had let her down. But then, on the fourth paper, not in the business section, as she had supposed, she found herself staring at that which had stayed in her retentive brain for no particular reason.

It was a picture of one very good-looking, self-assured male, attending some gala evening. Just good friends? asked the caption, plainly referring to the glamorous and sophisticated-looking brunette hanging on his arm.

Jack Dangerfield, chairman of J. Dangerfield, Engineers, with his current lovely. Will Gina Sansome have more luck with the wily bachelor?

With her heart pounding Leyne studied the picture of the tall, dark-haired man. John Dangerfield, obviously known to all and sundry—with the exception of her mother—by the well-established diminutive form as Jack.

He was good-looking, far too good-looking for his own good in Leyne’s opinion, and, by the sound of it, still unmarried. And that annoyed her—he was running around fancy-free while Max had had to make sacrifices here and there in order that their daughter should want for very little.

Reading on, Leyne thought he looked to be about the same age as Max, perhaps about a year or so older. Young, however, to be chairman of a problem-solving firm of engineers who apparently, so she read, had an international reputation. Well, all she hoped, Leyne mused, was that as well as solving safety engineering problems, he could safely help her solve this particular nearer to home non-engineering problem.

Wondering if the fact that he must have been extremely ambitious to head such a well-respected company at his mid-thirties age was the reason why—not wanting to be tied down—he and Max had parted company, Leyne went to where they kept the telephone directories.