По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

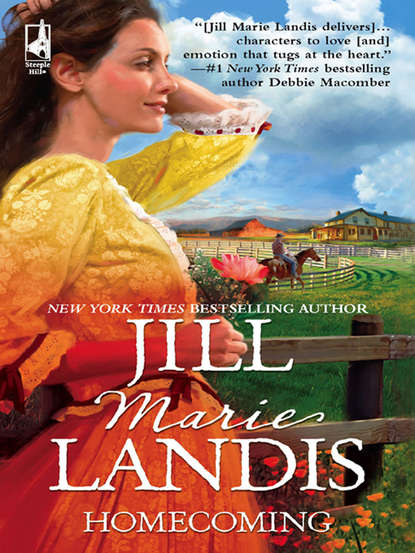

Homecoming

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Why not just eat out of the pots with their hands?

Then she carried the heavy container to the door, across the porch, and tossed the water over the side. She heard Joe’s voice in her head. Good.

Hattee-Hattee often spoke the word. Good job. Good girl. Good Book. Good.

She did as Joe commanded and he said, “Good.”

He was pleased.

For the first time since the raid, she felt lighter inside.

When she reached the main dwelling, the lamp was lit in the big room, but neither the woman nor Joe was there. She heard him speaking softly to Hattee-Hattee in the woman’s sleeping place but couldn’t make out their words, just the hushed sound of their voices.

It was the first time she’d ever been alone in this part of the dwelling without one of them watching her. She walked over to the flame inside the glass, the lamp, and held her hand above the opening, felt the heat. She had seen them turn the small golden wheel on a stick around, saw how the movement made the flame grow and shrink.

She glanced over her shoulder and listened.

Then she reached out, touched the end of the little wheel and turned it slowly. When the flame captured in the glass grew taller, the room became brighter.

Quickly she turned the wheel the opposite way and the flame shrank down and the shadows expanded in the corners of the room.

She clasped her hands behind her and continued to walk around the room, exploring, learning without having to be watched like a curious child. She fingered the cloth hanging from the round table near Hattee-Hattee’s moving chair. Then she placed her hand on the back of the chair and gave it a slight push.

It started to rock back and forth. She pushed it again.

It continued to rock. She waited until it was still again and then, taking a deep breath, she turned her back to it, grabbed the sides the way Hattee-Hattee did, and sat down. Hard.

The chair flew back so far that she gasped. She clutched the sides of the chair and when it settled down without bucking her off, when her feet were safely on the ground again, she bit back a smile.

Then she lifted her heels, pressed her toes against the floor and shoved. The chair flew back again, this time so far that a sharp cry escaped her. For a moment she seemed suspended in air and knew that she was about to go over completely backward.

Instinct made her rock her head and shoulders forward to protect herself from the crash. The chair obeyed, followed her movement, and settled back into place. It was not unlike taming a wild pony, she decided. And almost as thrilling.

Feeling quite proud of herself, she was about to make the chair rock again when she realized Joe was at the far end of the room, watching her.

His face was in the shadows and, though she couldn’t see his expression, she knew he would be angry. She braced herself for his wrath and slowly stood, careful to hang on to the chair so that it wouldn’t buck her off.

She waited, frozen in front of the rocking chair.

He took a step into the room and she knew the moment he remembered the rifle. His gaze shot to the entrance of dwelling, to the place where he always left the rifle when he came inside. She knew he took it to bed with him. Knew he would not hesitate to use it if she gave him cause.

His eyes shifted back to hers. No words were needed for her to know that he was upset that he’d left her alone with the weapon.

That he’d dropped his guard.

And what of her? What kind of a Comanche was she that she hadn’t thought to use it to destroy her enemies?

Her stomach lurched. She’d been here fewer nights than all the fingers on both hands.

When had she stopped thinking of these people as her enemies? When had the idea of escape slipped to the back of her mind?

Even now, she was closer to the rifle than he. In two steps it could be in her hands.

Silence lengthened between them. She reminded herself to breathe. Could he hear the frantic beating of her heart?

He did not move, but watched, tensed and waiting for her to move first.

The silence stretched between them.

He might be across the room, but still he towered over her. Tall as the man who was to have been her husband. Broad and strong. She might be able to grab the rifle, but she would need time to raise it to her shoulder, to aim and fire.

He’d be on her by then, be able to throw her to the ground.

And then what? He would beat her. Kill her. Or worse.

Their fragile truce would end if Hattee-Hattee were to die.

“Hattee-Hattee?” she whispered.

As soft as they were, her words filled the room. He did not laugh at her speech this time.

“In bed,” he said.

She understood his words and the same exhilaration she’d felt while taming the chair that rocked and the flame in the lamp swelled inside her. She understood. Hattee-Hattee was asleep.

But she had no idea how to ask after the woman, no words to aid in finding out if Hattee-Hattee was ill or simply weary.

Was a white woman allowed to sleep before her work was through simply because she grew weary? If so, Eyes-of-the-Sky could not comprehend such a thing.

Hattee-Hattee’s Good Book sat on the table beside the rocking chair. Eyes-of-the-Sky turned slightly, touched it, then looked to Joe.

He shook his head and then rubbed his hand across his jaw before he said, “Nottonight.”

He spoke too quickly and confused her, but she recognized the head shake, a sign for no, and understood that Hattee-Hattee would not be holding the Good Book and speaking in her singsong voice tonight.

The disappointment she experienced surprised Eyes-of-the-Sky. The words the woman spoke over the Good Book were incomprehensible, and yet, whenever Hattee-Hattee held the Good Book on her lap and looked down at the marks upon it, a calmness came over Eyes-of-the-Sky and she knew she would be able to face another day of imprisonment with these strangers.

“I’ll be all right. Don’t worry, Joe.”

It was nearly midday on the next morrow. The sun beat down on the plain, drying out the sodden land.

“I know you will, Ma.” As he said the words he wanted to believe they were true, and yet Joe knew well enough how fragile life was here on the Texas plain.

His mother was feverish, lying on her side, her knees drawn up to her chest beneath the heavy wool quilt she used as a winter spread. There was nothing left in her stomach, but now and again, spasms still racked her body. She’d been dry heaving into the bucket he’d left beside her bed when he walked in.

Deborah hovered behind him. He couldn’t see her, but he felt her presence. He’d kept her nearby all morning long.

Afraid to leave her in the house with his mother so ill, he’d made the girl work beside him the way Hattie had done all week.