По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

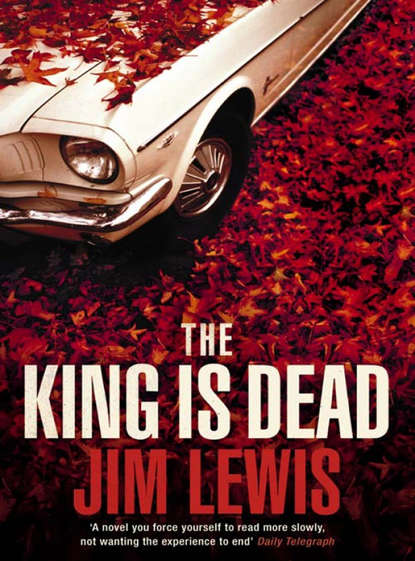

The King is Dead

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I want to go dancing, said Lukas. Let’s go find us a dance somewhere. You a dancer, Coonass?

Chenier nodded, his face serious and proud. King of St. Tammany Parish, he said. Ain’t nobody better.

There’s a big band down at the Regis Hotel, said Walter. Let’s go, then. Let them swing.

Let them swing, said Lukas, and they rose a little unsteadily and started back into the night.

The hotel ballroom was dark but the bandstand was bright, the music was hot and loud, and Chenier could dance just as he said, jitterbugging furiously, with his hat clenched in one hand and a local girl grasped by the other, his lined face shining and a smile fixed upon his features. Walter watched him with a combination of curiosity and admiration, as if the other man were an exhibit of some sort, a demonstration of human physical skill taken beyond the practical and into festive excess; and he danced one song himself, with a tall, heavily made-up woman with straight black hair and ocher skin, and then retired to the bar, where Lukas and Hamilton III were waiting.

Look at that man go, said Lukas. Chenier had loosened a button on his dress shirt and his legs and arms were flying this way and that.—He looks like a goddamned rooster trying to fly. Can’t compete with that: let’s get drunk. Bartender! You got any bourbon in behind that fancy bar of yours?

Then it was midnight and the band members were taking their bows, there was applause all around, and the three of them were as blind as worms, as bent as worms and with as little left to lose. Last hours on earth. Outside, the palm trees were being whipped around by a dark Pacific wind; inside, Hamilton III was lecturing to no one. My mother … he started, and then he stopped again, as if mentioning her was all he had intended. Coonass had come off the dance floor soaked in sweat, his hair as wet as if he’d just stepped out of the ocean. A big round-faced sandy-haired boy was waiting for him at the bar, watching him as he came across the polished floor, finally laying hands on the bar top and huffing for air as he gazed down to the far end, where the bartender was wiping up a spill.

Tell me something, nigger, said the sandy-haired boy. He wiped his small bent nose with the back of his hand and sucked back the water from his lips.

Chenier shook his head. Not so, he said, though he was so breathless it came out in a single slurry syllable. It made no difference at all. The sandy-haired boy put his hand on Chenier’s shoulder and squeezed a little.

Tell me, how did you get in here? You’re a sneaky little son of a bitch, aren’t you? Sneak your way into a white man’s Marines, where you don’t belong. Sneak into this hotel.

Down the bar Walter noted a certain dissonance in one corner of his consciousness, but it was late and he didn’t want to look, so he turned slightly, facing himself a little farther toward the dance floor, where a pair of Red Cross girls in chiffon dresses were holding hands and giggling about something.

You’re crazy, Chenier said to the sandy-haired boy. I don’t need no trouble.

Yes, said the boy. Yes, yes, yes. Yes, you do need trouble. Why don’t you come outside, and I’ll show you what you need? Come outside, and I’ll shove your black head up your black ass.

Chenier said nothing and didn’t move. The sandy-haired boy smiled and nodded to a pair of friends who were standing in the corner; the two friends smiled back, and then turned and left the bar. Idly, Walter watched them go. He studied his hands; he gently rocked his glass. Chenier caught the bartender’s attention. Shot and a beer, he said, and he cocked his head up to look at the chandeliers in the mirror behind the bar.

You can’t serve him, said the sandy-haired boy. The bartender made a puzzled face. Don’t you know who this man is? the boy continued. The bartender shrugged. This man, said the boy, is of the African race. Now … now … now, I don’t know how he got here, I don’t know who he lied to, or what. I don’t even know why he’s trying to pass. They’ve got plenty of places of their own. But I’ll tell you this, he insisted, leaning over the bar top. You keep serving him, and no white man is ever going to want to come in here again.

That’s enough, said Chenier. In the dim light he suddenly looked very much older, more formidable as a man, but also more frail.

It’s not even close to enough, said the sandy-haired boy, leaning in, and Chenier sighed. Come on outside, and we can settle this real quick.

Can I get a drink, my friend? said Chenier to the bartender.

Why don’t you boys take care of whatever you’ve got between you, said the bartender. Go take care of it, and then you can come back in and have a drink, O.K.?

The sandy-haired boy waited while Chenier stopped by Walter’s end of the bar to pick up his hat. By then Harrison III had begun the saga of his mother, her many marriages, her money, her mansion. The Cajun paused and leaned in to listen.

What’s going on? said Walter.

I don’t know…. said Chenier, slowly. This boy here seems to have a problem with me.

The sandy-haired boy smiled and spoke loudly from down the bar. I’m going to teach your nigger friend a lesson, he said, but Walter made no effort to argue with him; he was too drunk to quite register the insult, there in such crimson luxury with women and music; it caused him little more than a thought to the wind outside and his home back home. There was a bit of banal silence, and then the other two were gone.

The Cajun died that night, beaten to death in five minutes in the night behind the hotel’s service entrance, by three men who were never found. At the end there was steam coming off of him, but he was shivering, and the last thing he saw was a big dirty grey cat licking at his ankle. Skk, said Chenier. Skk.

It was only when the M.P.s entered the ballroom that Walter, Hamilton III, and Lukas realized that anything was wrong at all. They’d noticed that the Cajun was missing, and they knew he was in some kind of trouble, but they’d figured it was just going to be a little bit of pushing, something in the dark that any one of them might have confronted. Maybe he’d made friends with the sandy-haired boy and gone off to other pleasures. No.

The policemen separated them and brought them back to the station; there they were questioned, one by one: What are your names, and what unit are you from? Where have you been tonight? What have you been doing? Who was your friend? Who was he talking to at the bar? The three of them, Hamilton III, Lukas, and Walter himself, had hardly looked at the boy long enough to see him; they had heard the word nigger, and that had told them everything they needed to know. You didn’t see him? said the investigating officer to Walter. Your buddy goes out to fight three other men, and you don’t even see who it is? Why didn’t you go with him? Why didn’t you help him?

Walter was eighteen years old and had nothing to say, though a mad tear of dishonor slipped down the side of his nose. The drinking had long since left him, and their loss was strange; no one was supposed to get hurt until combat, and then only gloriously. No one was supposed to die upon dancing. Back at the base the three who were still alive had their last conversation. God damn it, said Lukas. Why’d the son of a bitch leave us? Why didn’t he ask for help? But all of them knew that they had done something too indecent to be washed away by sunlight or sobriety, or even the war to come. They had been careless and star-cursed, and Chenier had died.

18 (#ulink_4d9e3763-35c6-5687-b570-1afc43d5f910)

The following week Walter Selby boarded a transport ship bound south for the Gilbert Islands. Riding on the back of the giant greygreen ocean he waited patiently to die, to be cut in half by a shard of metal come whistling down from the empty sky, to be thrust upward on a column of fire, to tumble overboard and drown in the deep—not so much because he deserved it as because he was out of moral luck. Instead, the seas turned gradually blue, the islands appeared, the gorgeous jungles, coral reefs, a lagoon, a beach; forward and forward, under the palms and pandanus and in the event, he discovered how clever he was at killing men, and he killed every man he could.

19 (#ulink_9a2a7427-3fe8-55c6-93eb-fe2f1553373d)

He came home half skinned, with a nice medal to cover his rawness. His brother Donald was waiting for him in Louisville with a handshake and a proud smile, belied only by a little tightness around his eyes, where the war would not be forgotten. Everyone Walter met wanted to congratulate him, to call him, hire him; there were car horns blowing all over Louisville, and the lights burned in the house through the night. College went by quickly; he had a history professor who insisted he was made for public service and coaxed him into attending law school at Vanderbilt. Six years after peace had resumed, there were still people who remembered how well he’d done when war was at hand, and when he graduated he was asked to help out with a local campaign, a congressman whom no one believed stood a chance of reelection. And then, to everyone’s surprise, his candidate had won, and Walter felt a deeper and deepening satisfaction. After the War there would be no wars but that for the security and justness of Tennessee. He’d been offered a job in the Congressman’s office, but he declined: the Congressman himself was not inspiring, and his seat, in the lonely east, had no power to lend. What’s more, Walter liked the campaigning, the knowing, moving, and fixing. He was a young man with an authority that seemed inborn, thoughtful and stern, an educated man who nonetheless liked to get down on all fours and fight, a formidable man getting more formidable, a force to be feared or a comfort to those he cared for.

One winter afternoon, Walter received a call from a state senator in Nashville. He had heard a bit about the man: soft-spoken, frank, well trusted by his wan constituents, who had voted him into his father’s office a few years after his father had died, and kept him there for more than a decade. He was known to be thoughtful and thought to be fair; all his legislation had been sheer windmilling to the State’s higher machinery, but the people in the small towns, the failing farm communities and the middle poor, loved him for his promises and his undisguised contempt for the old men in the capital and Boss Crump’s machine in Memphis. He was more interesting than most, and Walter went to meet with him.

The senator had an elderly, tremulous factotum waiting in his anteroom who guided Walter into the office, disappeared, and returned a minute later with a tumbler full of Tennessee whiskey, a seltzer bottle, and a porcelain bowl filled with ice, which he set down on the table by Walter’s elbow. The Senator will be with you shortly, the factotum said, and took his leave again.

After a few minutes, the door opened and in came a small slight man with a great big round head, and hair and eyebrows so white he might have been an albino; but he was merely old, and stripped clean of color by the speed with which it happened. Walter stood; the senator shook his hand softly and motioned him to sit again, taking a winecolored leather chair himself and drawing in a long breath.

Walter Selby … said the senator, gazing at him frankly. You’re a big fellow, aren’t you? That’s good. I like that. He took a moment to look at the papers on his desk. Walter Selby: I’ve been hearing about you. Walter nodded, and then there was silence, but for the airs of the house around them. At length the senator spoke again. Do you know how far it is from Memphis to Sugar Creek? he said.

About five hundred miles.

Four hundred and seventy-five, said the senator. That’s a long way. A lot of highway. Our truckers are getting shaken down all along it. We have to do something about that. We’ve got to help the farms a little, as much as we can. We’ve got some classrooms with forty-five children in them, and others with just two or three. It doesn’t make any kind of sense. We’ve got utilities up in arms about the TVA, and people still don’t have power in some parts of the state. No power. No lights, no refrigeration, no radio to listen to after dinner. There are people who believe that the only solution to our problems is World Government.—The senator paused to taste the words.—World Government. Over there in Memphis there’s a group of businessmen, meet in secret every Thursday night at the Badger Room to discuss the establishment of a … World Government. There’s another group, meets in secret every Monday at noon in the back room of a luncheonette on Union Avenue, to discuss how to thwart the first.—The senator held his hands up in an attitude of prayer and pushed them against each other. You see? he said. Two opposite and equal forces. I’ve taken them both aside and told them how much I appreciate what they’re doing. Told them, I can’t come right out and endorse you, of course, but you have my tacit support and my gratitude. And they do. As long as they keep pushing against each other, they can’t push against anyone else.—Here the senator shook his head sadly. Sweet Jesus, the state’s crawling with lunatics. Half my job is keeping them howling at the moon, so they don’t start howling at me. I was talking to a doctor down at Vanderbilt the other day, man working on an immunization program. A good program, too, and I’m going to get behind him. Then I asked him: When are you boys going to come up with a vaccine for foolhardiness? That would solve about half our troubles right there.

Walter smiled slightly.

All right, said the senator. Let’s talk.—He leaned back in his chair, paused, and then leaned forward, until Walter could smell his clean breath and barbershop aftershave. I saw what you did in that campaign. I watched you pretty closely. You’ve got your war record but you’re not riding it all over the state. You’ve got family ties here from a long ways back. I know all about it, don’t you worry. Nothing to be ashamed of. There’s probably a little colored blood in all of us.

What? said Walter.

Old Lucy Cash, she did what any woman in her position would have done.

The name had come from so far back that Walter had to pause and think.

You didn’t know, did you? the senator said softly.

That’s my great-grandmother.

She was a colored woman from Chicago, said the senator. High yellow, a lovely girl. She wanted to pass, so she came down here.

Walter shook his head, looked down, and studied his blood—the same blood now, but it felt burnt. Where did you get this from? he said.

Well, you know, I looked into things, said the senator. I wanted to know who I was talking to. The important point is that it’s not important. Do you see?

Walter nodded and said, No. A pause. No, of course it’s not important. I bet half the people in Tennessee have some Negro blood in them somewhere.

That’s right, said the senator. That’s what I’m saying. But I don’t think people are quite ready to hear that yet. Not today, anyway. Maybe tomorrow.

Maybe, said Walter. Tomorrow. Is that why you and I are meeting?