По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

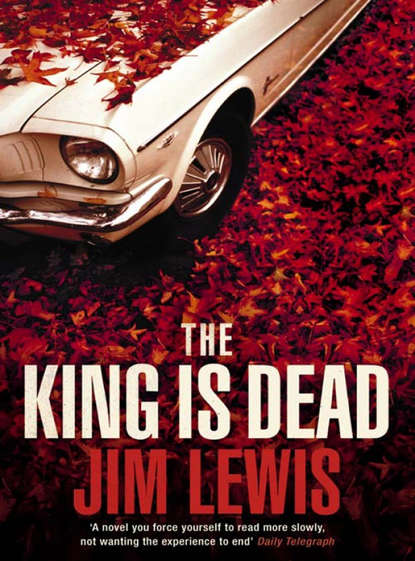

The King is Dead

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

What’s the Navy Cross? said George.

A bit of ribbon, said Walter, and a bit of bronze.

Did you fight Germans?

You don’t use a navy to fight Europeans, said Peter.

Of course you do, said George. There’s a whole ocean between us. They had U-boats. They had a navy.

I fought Japanese, said Walter softly.

The car was quiet. They were passing over a bridge, the water below was pitch black and as smooth as glass, and Nicole reached over and briefly touched Walter’s arm.

Then they were at his door, and she was stepping out of the car, leaving him room to exit. Good night, you all, he said.

Five good-nights came back. He stood on the sidewalk, slightly turned away from Nicole, as if he couldn’t quite bear her brightness full on.

Thank you for taking care of me, she said.

You’re welcome, he said. It was a pleasure. Good night. He nodded gently and started up his walk, looking back at the girl when he was halfway to his door. She was standing beside the car, she smiled at him again with her effortless jubilation; then she waved good-bye. And she climbed back in, and the car drove off, leaving him there in the quiet of his neighborhood, in the center of his tiny little lawn, which stretched for miles and miles to his lighted front door.

3 (#ulink_7846e503-3536-5ea6-a000-ad1744d94ba0)

Back in the days when days were new, Nicole had met a man named John Brice. That was in Charleston, it was early in the fall, and all of her friends had thought he was strange. Yes, they said, he was handsome, lean and graceful, but he was strange. To begin with, he’d just appeared on the street one April day—Nicole had seen him standing outside the Loews in the middle of the afternoon, waiting all by himself for a matinee to begin—and then again, there he was on Broad Street a few days later. After that it was time to time; he was always alone, often with his hands thrust into his pockets. Sometimes it seemed as if he was dancing a little bit, dancing to himself as he went on his way. She’d seen him, a tall slim fellow with refined, almost feminine features and his hair combed back.

At the time she was just out of her parents’ house; an only child, imaginative and open. She’d spent two years in junior college, and then she came home again, took an apartment with a girlfriend named Emily, and started working in a women’s clothing store called Clarkson’s: some dresses, some underthings. Just a job, although she took pleasure in the details of the place, the feel of her fingers stretching over satin or the resistance of a band of elastic. Mr. Clarkson was usually at home, tending to his sick wife, so most of the time the store was hers; she even had keys to open it in the morning and close it at night, with only an hour or two toward the end of the day when he would stop by to empty the till and deposit it into the bank across the street. Otherwise, there she was, alone amid the cloth, the silks and nylons, and the ladies who came in.

This man, he must have been new in Charleston but he strode down the sidewalk as if he’d put a down payment on the whole town. That was something you noticed right away. Still, she didn’t think much of him; he was not-quite-regular and all alone, and it didn’t take much to make a young man wrong for a girl, in that city, in those days. At first she couldn’t quite tell what it was, exactly, and then it came to her: there was a slight eccentricity in the way he dressed, nothing that most people would have heeded, but she had an eye for the way a man put himself together. He would pass her on the street, wearing a pair of black dress shoes, perfectly acceptable, except that the laces were mouse-grey, and he had doubled them through the eyelets before he tied them. Was that on purpose, or couldn’t he shop for something as simple as shoelaces? One evening when she was walking home from work she saw him standing outside a florist’s in a seersucker suit, quite a nice one, actually, with narrow stripes of a deep rich blue; but it was a little bit late in the year to be wearing summer clothes, late enough that you would’ve thought he would be cold; and his belt was a few inches too long, so that the extending tongue turned and fell a few inches down over his hip. It was just the kind of thing she would notice, and she crossed the street instead of passing by him; but he turned and watched her all the way down to the end of the block, and she could feel his attention dragging on her at every step.

Then he came into Clarkson’s. It was a Tuesday, late in the morning, and he opened the door, peered in for a second, and then slipped across the threshold. He didn’t say a word, he just moved among the dresses and the blouses, along a line of girdles, back and around and back again, while she followed him from behind the counter and thought, What is this man doing? He took a little half step sideways—very gracefully—and she stood perfectly still. Then he did a little dance, maybe, a few subtle steps almost too soft to be seen at all, a slight gesture with his hip, his head cocked. He glanced up at her, studying her face, and she would have reddened before his eyes—but just then the telephone rang, she looked down at it, and he suddenly turned and left the store before she’d even had time to pick it up.

Then there was her father’s fiftieth birthday party, marked by a family gathering in their house outside of town—she remembered the weekend well and long afterward. So goes the tone of a time: not just forward over everything to come, but seeping outward too, in every direction, like wine on the figures of a carpet. She helped her mother in the kitchen, there was an aunt who got drunk at the party that evening, and wept noisily all night at something no one else had noticed and the woman herself couldn’t explain. That night Nicole slept in her old bedroom and listened to her parents in the room next door, arguing in soft voices and then, worse, giving in to that silence which had frightened her so when she was a child, and still made her uneasy. Poor father: a few years after she was born he’d contracted a fever, which was polio and paralyzed his left leg from the hip down. Poor mother: a local beauty alone with an infant, her husband quarantined and perhaps never to come home. By the time he recovered they were strangers again, the large family they’d dreamed of was not to be, he retreated into hobbled quiet, and she wore a seaside cheerfulness everywhere but on her mouth’s expression. Now Nicole listened as her mother sat heavily on the edge of the bed, and her father cracked his knuckles as if he would break his fingers right off.

The next day she was back at work, and that very afternoon John Brice appeared again. The same man, he walked around the store a little bit and then left. But she knew he was going to come back again, she knew she was going to know him, and she waited for him; a few days went by, and then right when she’d decided to stop thinking about it, he opened the door and came in. He had a look, didn’t he? Not just his expression, which was ready, but his clothes. This time he was wearing a grey double-breasted suit and a wide blue-and-grey tie, a foppish outfit, kind of high-toned, she thought, although he wore it very casually. He ambled up to the counter where she stood. Hello, was what he said.

She should have just said hello in return. Instead she fell back on her shopgirl manners. How may I help you? she asked.

He paused. I was just looking, he said, and motioned to the inventory with one long pale hand.

Anything in particular? she said

No…. He shook his head a little.

Maybe if you tell me who you’re shopping for, I can recommend something. The sun outside the windows shone down on an empty street, and she looked up and read the name of the store imprinted backward on the inside of the day-dark yellow glass.

What’s your name? he asked. She didn’t expect that, and she hesitated. It was something she didn’t want to give away, because she knew she’d never be able to get it back. Come on, now, he said, and made her feel foolish.

Nicole, she said at last. Lattimore. It was as if all the dresses and underthings were filled with silent women, watching women: were they smiling or shaking their heads? It didn’t matter anymore. It was done, really, with that. She gave him her name, and that was all he needed.

4 (#ulink_bc4114c5-a6d2-57af-ae94-c3831ec8b099)

On the third weekend after they’d met he invited her for a drive down to Sea Island and she accepted. He had a huge blue car, a Packard Coupe that he’d bought almost new a few weeks after he’d arrived in town; he came to get her at the hour they’d set, just past dawn, and parked outside her apartment building, but he didn’t ring her buzzer. She only realized he was there when she grew impatient waiting and put her head out the window to see if he was coming; then she went hurrying down to him, though she didn’t chastise him for not coming to her door. It seemed like one of his things, she could let him keep it if he wanted.

It was a long way, and chilly, and he drove fast, flying along the edge of the ocean, beside inlet and alongside islet, blue outside his window and green outside hers. On Sea Island they bought a basket lunch from a general store, then parked by the ocean and scared the seagulls off the sand with the car horn. Later, they kissed until her lips were sore and her tongue tasted just like his. They arrived back in Charleston that evening; it was too late for dinner, really, but he was hungry, so they stopped for a hamburger. She asked him what he intended to do with his life. She thought it would be a good way to begin to get to know him.

He didn’t hesitate and he didn’t look away. I’m going to be a bandleader, he said, and for a moment she couldn’t imagine what in the world he was talking about. Play the saxophone, jazz, he went on, and he held his hands up, one above the other, gripping an imaginary instrument and wiggling his fingers. Jazz, jazz, jazz. New York, Chicago, maybe Los Angeles. I’m going to be famous.

At first she thought he was joking; it had never occurred to her that a man could have such an ambition, that wealth and fame could be studied, rather than simply stumbled upon by those with improbable access to the unreal. Oh, you are? she said teasingly, and she saw him wince. I’m sure you have the talent, she added hastily, and you certainly look the part. But isn’t it difficult to break in?

Sure it is, he said. He paused. I’ve got a little luck, he admitted. My father, over in Atlanta—he has some money. He stopped again, as if he was suddenly embarrassed by the rarity of his fortune. My father is what you might call … a wealthy man. He doesn’t much approve of what I’m trying to do, but he’s willing to support me for a little while.

Then why did you come to Charleston?

My grandfather had a house here, he said. When he died, he left it to my parents, but they never use it. So I came up here to get away, to practice—you know. To get myself ready.

Ready, she thought. Odd syllables. Was she ready, herself? The more she thought about the word, the stranger it became.—And here was the waitress with the check, it was time for him to take her home.

5 (#ulink_113225f6-80cb-547e-b2bc-909899c5ea25)

Things about him that she loved: He was tender and devoted. He was funny, and though she’d never actually seen him on stage she was sure he was very good, and so dedicated that he was bound to be successful. He needed her in order to be happy, and he never hid the fact. He never hid anything: he wore all his emotions on his face—ambition, amusement, amorousness. He had that odd, faintly extravagant style, not just in his clothes but in almost everything he did, from the drink he ordered—a martini, bone dry, three green olives, on the rocks—to the language he used when he was excited. He was optimistic all the time, and negotiated the world with an ease that couldn’t be gainsaid.

Things about him that she never could be comfortable with: He spoke to her as if he were trying to coax her over a cliff. He judged the world immediately around him severely and without sympathy. He was moody. He had no other friends but her. Many things had come easily for him—money, for example, and self-confidence, and a sense of purpose—and he didn’t understand that those things didn’t come for her at all. He could be stubborn and impatient. He was more sure of his feelings for her than he should have been, and there was no reason why he might not change his mind. He was a field in which disappointment grew.

In later days they would go to the movies, and afterward he would do imitations of all the parts, the leads, the character actors, bit players, the women too, his voice cracking comically as he reached for the higher notes. Some of his impressions were startlingly accurate, and some of them were just terrible, and the worse they were the more she adored them. Then he would drive her back to her apartment, and, because she had no radio, they would sit outside her building, listening to swing while they kissed under the shadows of a tree—once for such a long time that the battery ran down, and when it was time for him to go home he couldn’t get the engine started, and he had to call out a truck to come help. After that he made sure to start the car every half hour or so, letting it idle for a few minutes while they went on with their talking, necking, talking, their raw rubbing at each other.

Oh, how much she loved that car, the shallow, intoxicating smell of its upholstery, the chrome strips—like piping on a dress—that bordered the slot where the window sat, the white cursive lettering on the dashboard and the fat round button that freed the door of the glove compartment. These were elements with which she shared her sentiment. Did he ever know? His keys hung from the ignition on a chain that passed through the center of a silver dollar, the thick disk spinning when the car shook; it was emergency money that his daddy had given him back when he first learned to drive, though when she pointed out that it might not be spendable with that hole in the middle, he just smiled as if she’d deliberately said something amusing.

He might have had some money but he had no telephone, so he would call her from a public booth in town, not always the same one; he would be standing by the railroad terminal, in the library, on a street corner. She couldn’t call him at all—she never quite knew where he was—and she grew more and more frustrated with waiting. She tried to show him but he didn’t seem to notice. He called her at home on a Thursday night at nine. I can’t talk right now, she said. Let me … she sighed. Well, I can’t call you back, can I? she said pointedly. Call me tomorrow.—And with that she hung up on him and went back to her reading, though the page in whatever it was trembled, and the letters shook themselves out of order. When he called her at work the next day, from a phone booth in a filling station, he never asked her what had kept her from him the night before. Wasn’t he curious? Didn’t he care? All that evening she was in a sullen mood: All right, she said shortly, when he suggested another movie; she sat upright in her seat in the theater, and neither stopped him nor responded when he put his hand on her arm and then slid his fingers down to her wrist, from her wrist to her knee, her knee to her thigh. He started up between her legs and still she didn’t move at all, so he withdrew.

He took her to a cocktail bar afterward; she hardly said a word the whole way there and sat across from him, rather than beside him, in the darkened booth. Are you all right? he said. He was wearing a beautiful grey shirt.

I’m fine, she said, her fingertip playing distractedly across the lip of her martini glass. She waited a moment, and then she said, I don’t think we should date anymore.

He widened his eyes and slumped back in his seat. No? he said.

I’m sorry, said Nicole. I just don’t think we should.

No? he said again, as if he was hoping that No said twice might mean Yes. Will you tell me why?

He was hurt, and whatever gratitude she might have felt for his exhibition of caring quickly gave way to guilt, so she drew back from her anger and offered him a deal. She couldn’t bear to wait by the phone, but they would be fine if he would call her regularly, at work just before noon to make plans for the evening, if plans were to be made; at home before nine if there was nothing to say but hello.

It was their first bargain, and he kept his end carefully, mornings and evenings. There was nothing romantic about the routine, not at first; it was just John calling the way he had promised he would. And then it was romantic, after all, and October turned into November.

6 (#ulink_eefbe5fc-8ab9-5ced-8b65-cae112163242)

Now tell me, because I don’t know, she said one afternoon. Where do you live? He had arrived at her door in his car again, and it had occurred to her, not for the first time, that she didn’t know where he was coming from. He seemed to prefer it that way; anyway, he never volunteered to tell her. If she had to ask, she would ask: Where do you live?

He shrugged. Up in the woods, a few miles out of town, west. She waited. It’s just a little house. He traced an invisible house in the air with his fluid hands. Up in the pines, about ten miles from anywhere. At night it’s so quiet, all you can hear is the wind and the wolves carrying on.