По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

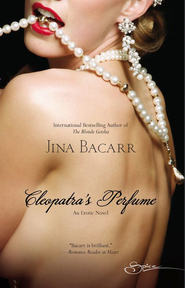

The Blonde Geisha

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I heard my father give the boy instructions where to take us, the boy nodding his head up and down. He bowed low before raising up the adjustable hood of steaming oilcloth covering us. A canvas canopy arched over the seat to protect us from the rain.

“Hurry, hurry!” Father shouted with urgency to the driver, then he sat back in the two-seat, black-lacquered conveyance.

The boy grunted as he lifted up the shafts, got into them, gave the vehicle a good tilt backward and took off in a fast trot.

I had no time to ponder my fate as the boy snapped into action and pulled the jinrikisha down a street so narrow two persons couldn’t pass each other with raised umbrellas. I thought it unusual the boy didn’t shout at the few passersby to get out of our way as most drivers did. Instead, he ran in silence, his heavy breaths pleasing to my ears. I kept trying to see his face, but every time I peeped out of the tiny curtain, my father yanked me back inside the jinrikisha.

“Keep your mind on our mission, Kathlene.”

“I’m trying my best, Father, but you’re not telling me everything,” I dared to blurt out. Worry for his safety made me anxious.

“I can’t. All you have to know is you’re my daughter and you’ll act accordingly.”

Angry, I crossed my legs, my black button boots melting into the softness of the floor mat. I wiggled about on the red velvet-covered seat, trying to get comfortable in my wet clothes and sinking down lower into the soft cushion. I didn’t mean to be disrespectful to my father, but I was frightened. Frightened of what lay ahead.

I looked over at him and went over in my mind the events of the past day and night, trying to understand why he’d ordered me to pack my things because we were leaving Tokio at once. Next he ordered our housekeeper, Ogi-san, to pack rice, pickled radishes and tiny strips of raw fish into lunch boxes so we’d have something to eat on the day-long journey ahead of us.

He’d hardly spoken a word to me since we left. I wished he would confide in me, as he often did. This time he said nothing. Instead, he ordered me to speak to no one.

“My life depends on it, Kathlene,” he told me, putting his right hand under his jacket, as if he hid a pistol there.

My father was a handsome man, but at this moment he looked funny, strange even, bent over in the tiny jinrikisha. His clean-shaven face was wet with rain, his head hatless, his hair matted. His rich, black overcoat glistened with dewy pearls of raindrops. Even his black leather gloves shone with a rainy sparkle that played with my imagination, hypnotizing me into believing this whole escapade was a game. That nothing was wrong.

For what could go wrong in this beautiful, vibrant green land of misty plum blossoms? Lyric bells played a song on every breeze and the sweep of brilliant red maple leaves harmonized with the melody.

To me, it was a gentle land inhabited by a gentle people. And the only home I’d known since my father brought me to Japan with my mother when I was a small child. He’d known my mother was sickly and the ocean voyage from San Francisco had weakened her, but Mother wouldn’t stay behind without him.

So she came. With me. My heart ached with fresh tears, trying to remember my mother. It was difficult for me. She died that first year. I never shared my pain with anyone. Especially my father. He seemed to hold back his feelings around me, yet I knew he loved me. That was why I didn’t understand why he acted so strangely.

What have you done, Papa? I longed to ask him, but I didn’t. I never called him “Papa” to his face. It was a term he didn’t understand. He was my father. No more. No less.

I held on to the seat as the thin, rubber-treaded wheels of the jinrikisha bounced over what must be a small bridge. I couldn’t resist peeking out the curtain again, but this time my father didn’t pull me back. I sighed, delightful surprise catching on my breath. Though it was near sunset, I marveled at the western hills throwing purple-plum shadows on their own slopes, the long stretch of wheat fields turning to a lake of pure gold by the drenching rain.

A splatter of rain hit my nose and I wiped it off, muttering in half Japanese and half English. I switched easily between the two languages, since I’d learned both at the same time. Japan had been my home for most of my life and I was proud of my linguistic ability. Though with my blond hair, I often felt strange in this land of dark-haired women. My father assured me I was going to be as pretty as my mother, though he knew nothing about my desire to become a geisha. I smiled. I know Mother would have approved. Geisha were admired by everyone. They were the most beautiful women: the way they walked, their style and their spirit.

I sighed again, letting out my frustration in one big puff of air. I’d never be a geisha if I stayed in a nunnery. I’d be doomed to a life of joyless obedience, days praying and nights filled with loneliness. The beauty and brightness of the world of flowers and willows promised so much more. For now, my dream to be a geisha was only that. A dream.

We’d been riding for an hour, maybe longer, and the green shadow and gloom hung lower in the sky. I could hear the cawing of the ravens living in the old pine trees as if it were a solemn chant welcoming me to my new home.

No, wait, it wasn’t the birds I’d heard, but a loud bronze gong sounding a long note as rain pelted the oilcloth hood covering us. I held my breath as the driver continued pulling the jinrikisha along the narrowest of lanes with trees arching overhead, blocking my view of the darkening sky.

Then as if by the will of the gods, the rain stopped. I listened and I could hear the noise of running water from little conduits by the road, nearly hidden by overgrown fernlike plants as we traveled deeper into the hills.

A little farther down the lane, the road came to an end.

The driver stopped and I could feel the vehicle being lowered to the ground. I breathed out, relaxed.

“We’re here, Kathlene,” Father said, though I didn’t hear relief in his voice.

“At the nunnery?”

“Yes.”

I wanted to run away. Far away.

I was aware of the stillness surrounding me as I got out of the jinrikisha after my father, my legs stiff and my feet wet. I looked around. Where was everyone? Monks and nuns could usually be found walking the grounds with their curious, basket-shaped straw hats hiding their faces, their palms outstretched for alms, their voices low and begging.

All I saw was a dull red gate standing in front of a stairway of steep steps leading up to a small temple with vermilion pillars supporting it with a heavy, gray-tiled iron roof. Hundreds of lanterns dotted the grounds, along with several statues of heavenly guard dogs perched on stone pedestals.

I almost expected to hear them start barking as my father bounded up the steps, his feet moving at a fast pace, his mood somber. I started to follow him, when I saw the most exquisite scarlet wildflowers growing in clumps around the steps. I was drawn to the flowers, their long, soft petals reminding me of the finest silk worn by the geisha. Dazzled by their beauty, I bent down to pick a cluster of flowers when—

Whooossshhh. Something flew by my face so fast I could feel a tiny breeze fanning my cheek. I touched my skin in surprise, and before I could reach down and pick the flowers, I heard the unmistakable crrraaacck of stone hitting stone and exploding into hundreds of fragments.

I turned my head around in time to see the head of a dog statue toppling from its body and landing on the ground, shattering into big, ugly pieces. Then I heard a voice cry out, “Don’t touch the flowers!”

Startled and shaken down to my pantaloons wet from the rain, I jumped back, looked around, and was surprised to see the jinrikisha boy. He had yelled out to me, breaking the stillness around us.

“Why?” I asked, not understanding. “What’s wrong?”

“Those flowers are poisonous,” the boy said, bowing, knowing he’d spoken out of turn, but as I was about to find out, most fortuitous for us.

“Poisonous?” A commotion in the sky caught my attention. I looked up to see hundreds of pigeons flying over my head, the whirring of their wings mixing with the neighing of horses. Horses? The nuns shunned the luxury of any kind of conveyance and walked everywhere. Where did the horses come from?

“These flowers will inflame your hands,” the boy said, “and make them red.” Then he bent down low and whispered hotly in my ear, “I’d like to make your cheeks blush red with the heat of passion.”

“Oh!” I turned away, my skin tinting a dark pink. A silver-spun mist of anticipation slithered across the soft opening between my legs. Then a hot boiling steam spread across my belly, arousing my senses. I was unsettled by the boy’s crude remark, but I was more disturbed by my own reactions. A new strangeness arose within me, which didn’t seem unnatural. I experienced an overwhelming desire to surrender to the raw, sexual energy of this new discovery. Yet I was afraid of some dark emotion I couldn’t define. Afraid of losing control of myself, doing wild things I’d never thought of until now, and then wanting more.

Summoning the courage to confront the need as well as the desire stirring within me, I dared to look down at the large bulge between the boy’s legs, my heart beating faster when—

“Get back into the jinrikisha, Kathlene!” I heard my father shouting in English. His voice sounded desperate. “We’re leaving!”

I saw him running back down the stairs, taking them two, three steps at a time. Something was horribly wrong.

“What’s going on?” I asked, a fresh wind picking up and bringing the smell of sweating horseflesh with it, the pungent odor lingering under my nose. I hadn’t imagined the sound of horses after all.

My father grabbed me by the arm, then pushed me into the jinrikisha. “They were waiting for us, the devils. Get in, now!”

I did as I was told, fear making my heart beat faster, my father shouting to the boy to take off down the narrow lane. I dared to look out the oilcloth curtain, my eyes searching out the steep stairway leading to the temple before my father pulled me back into the jinrikisha. I saw dust kicking up. Someone was coming after us.

The boy was running. Running. I could hear his heavy breaths comingquickly, then quicker yet.

“Who was waiting for us in the temple, Father?”

Faster, faster, the boy ran. He must have the strength of the gods in him.

“I’m certain it was the Prince’s devils. If that boy hadn’t yelled out and startled the birds and surprised their horses, I hate to think what would have happened to us.” He put his arm around me, holding me tight, though I could feel him shaking. “How they knew we were coming here, I don’t know.”

Heavy breaths. Thumping bare feet. The boy didn’t stop running.