По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

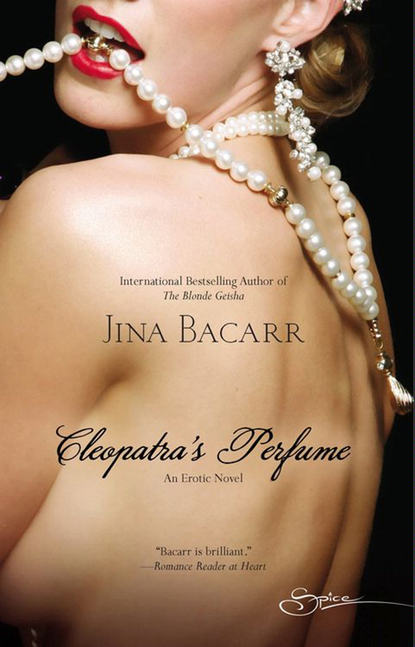

Cleopatra's Perfume

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I had arrived in the Near East as a girl of twenty in a time when rebellious girls dressed in red satin trunks and short tops and sat at tables in seedy cafés, sipping highballs in squatty glasses with men seated around them, their hungry mouths drawn back in drunken smiles while someone struck the same chords over and over again on an upright piano. I’m not ashamed of what I did during those wild days of my youth, but nor do I wish to recall them here. So, dear reader, whoever you are, be assured I knew what to expect when the liner stopped for stevedoring in Port Said and I disembarked from the ship. Known as a city of sin, rice and women are its main commodities. Port Said harbors a white slave trade flourishing in its hidden places, bars and houses, where young girls languish and perish under the thumbs of men.

I also discovered another secret in this city at the entrance to the Suez Canal, how a woman can forget her loneliness and indulge in the most delicious sexual adventures, so decadent I bring myself close to orgasm thinking about it, my pen shaking as I lay it down and unbutton my white silk trousers and insert my fingers inside me and stroke myself…panting, hanging in anticipation of what I know will come if I continue rubbing the hard ridge inside me, my body gyrating in time with the movements of my fingers. I open my legs wider to allow my fingers easier access…

Excuse the abrupt interruption, dear reader, but my need overcame my reason. I’ll be embarking soon on the first leg of my journey to Berlin, but first I must continue with my story and why I returned to the Near East after my husband’s death.

I’d enjoyed many pleasant interludes with Lord Marlowe in the region during our marriage: from the polo matches at the Gezira Sporting Club in Cairo, to excursions to see the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid, to traveling down the Nile to Luxor and Aswan. It was also where I could escape the suffocating air distorting the reality that dominated London’s clubs. I couldn’t survive in that atmosphere of pearls and perfect vowels, where one’s place in society was bred into the bones, though from what I’d seen in many a Mayfair drawing room, they grew brittle from a lack of blood flowing through their veins.

I packed my trunk and left London.

I was familiar with the sea route, having traversed it many times over the years with my late husband. After traveling from London by train to embark on a ship at Genoa, the luxury P&O steamer went on to Port Said and would then pass through the Suez Canal to Bombay, Hong Kong and Shanghai. What should have been a tranquil journey of reflection, I must admit, turned out to be a pattern of recurring neuroses. Chatter aboard ship became more stifling than staying in London. My independence was at stake. I had no place to hide from my fellow British passengers, many of whom knew of my recent widow status and whispered among themselves about the scandal brewing when word got back to London that I was traveling alone. And wearing white wide-leg trousers and an open white blouse with ample cleavage showing.

From behind my round dark glasses, I watched the gentlemen eyeing my pointy breasts and the ladies watching them. I shaded my eyes from their stares, but I had nothing to hide. White denoted purity of heart and I had every right to wear it. During my years of marriage to Lord Marlowe, I’d remained chaste, taking no other man to my bed; but now I was alone, and companionship was not something I merely desired. I needed a man and I needed him badly.

I disembarked the ship at Port Said to idle away time shopping for tropical skirts, pants, cameras, inexpensive jewels and French perfumes. Lucky for me, the shops remained open all night to cater to travelers until the ship departed in the early-morning hours. It wasn’t long before boredom, the heat and the flies, as well as the dirty looks from my fellow passengers, drove me to explore the port city on my own.

I doubted these ladies with their noses stuck up my business would dare follow me into a seedy-looking bar that reeked of male sweat and alcohol and with cigarette smoke so thick it drifted like a seventh veil over the crowd. I sat down at a small table and ordered Egyptian beer, what Lord Marlowe called onion beer because of its strong taste.

Raising my glass, I was congratulating myself on losing the gossipy women, when a slightly built Egyptian wearing a red fez with a long black tassel half covering his face shuffled over to me and bowed, then asked to tell my fortune. I shooed him away, knowing full well this wallah would gladly dish out what British locals called pukka gen— advice to the lovelorn—to any lone female willing to listen.

But he wouldn’t give up, insisting he had a special rate for a pretty lady with hair the color of the moon. I put down my beer and smiled at him. With a line like that, how could I refuse?

I invited him to sit down, and before the air could settle underneath his sagging body, he removed the lid of a biscuit tin from inside his shabby jacket and poured fine sand into it, then shook it until the surface was even. Then, taking my hand, he instructed me to trace lines in the sand with my fingers. I did as he asked, its soft touch making my fingertips tingle with what I knew was curiosity, not magic. When I finished raking my fingers through the white specks, he gazed at the squiggles I’d made, thinking. Then he began to speak. Slowly, as if he was reciting a well-rehearsed prayer.

“Your heart is lonely since the death of your husband.” He sighed, for effect, I’m sure. “And you crave a man’s touch to soothe your pain.”

How did he know I was a widow? Did he see the hunger in my eyes for a man’s sweat to mix with mine, his hard muscles pressing against my willing flesh as he rubbed his chest against my bare breasts?

He looked at me, but I cast my eyes downward. Not giving up, he continued, “I see you are as fragile as a flower in the desert, reaching up to the sun for nourishment, but dying without the sweetness of the rain to quench your thirst.”

No doubt this fortune would fit several lonely women travelers in this port city and I told him so. He shook his head, insisting there was more. He grabbed my hand again and raked my fingers through the sand. I saw him shaking, his lower lip twitching. My hand shook as well and I swear the sand sparked against my fingertips.

“You will meet a man within a fortnight,” he insisted, “and his fire will peel the skin from your bones, making you lose all control—”

I pulled my hand away. “Sounds unpleasant.” I tried to keep my voice steady, not let him see how his prediction affected me, nurtured the elusive dream I craved, but even as I said the words, my lower belly ached and my clit throbbed from want of a man I didn’t know.

The fortune-teller continued, “With him you will find immortality.”

I pondered this, though not for long. Immortality? What nonsense. What Near Eastern alchemy he was peddling I could only guess. I doubted I could find a man to fulfill the incompleteness haunting me since my husband’s death and assuage my hunger for the pleasures long denied to me. Still—

“Where will I meet this man?” I had to ask, wanting to believe I could escape my loneliness through this predestined encounter. I held my hands together in my lap to stop them from shaking. If I found such a man in Port Said and found sexual pleasure with him, that would mean I’d crossed the line into another world. I couldn’t go back. I sensed I was at a dangerous impasse by snubbing the staid world of British royals, forcing me to face what I thought I’d left behind: my taste for the sweetest of tortures. I’ll not regale you, dear reader, with details. They will come later.

“You will take him from the arms of another woman,” the man said.

I threw my hands up into the air. “I don’t believe your silly fortune-telling.”

“Believe. It will happen.” He jumped up and put out his hand. “Five piastres.” One shilling.

I paid him, though my face dripped sweat and my lips trembled as the smoky air seemed to close in around me and hold me in its grip. I couldn’t deny the physical reaction I had to his words. Whatever excuse I wanted to use, lonely, frustrated for lack of a sexual partner, I was ready to embrace whatever erotic impulses I discovered in this city of sin, ready to surrender to emotional chaos to feed my hunger without guilt.

I turned around to order another beer and when I turned back, the man was gone.

My hand was still shaking.

The fortune-teller’s words freed my spirit. I was like a bird released from its cage, not knowing I was the bait for bigger prey. I rebelled, ravaged my past and let go of my fears. Looking. Searching. Imagining. My need for sensuality clashed with my need to be rational, and won the fight.

I elected to remain in Port Said.

I returned to the ship and made arrangements for my luggage to be transferred to a hotel. Then I sent a cable to my secretary and oft-traveling companion, Mrs. Wills, in London, telling her I was staying in Port Said. A woman whose starched back never bends, her prompt response was one of concern as well as curiosity as to why the change in my plans. Bookish with gray strands weaving through her dark hair like a melody of lost notes, she cuts a slender figure in her proper dark suits and blucher-style brown oxfords. She’s an asexual creature who neither understands nor approves of my erotic adventures, but I value her friendship and advice. She rarely if ever ventures forth with a personal opinion, believing it isn’t her place to do so, but I would have never found my way in British society as Lady Marlowe without her.

I refused to admit I was profusely affected by what the fortune-teller had told me, his prediction disturbing me in an obscure, mysterious way. Over the next two days, I went out of my way to avoid men, peering over my sunglasses in a dismissive manner whenever a gentleman spoke to me, as if I was testing the fates and their uncanny way of making things happen when we fight against it. But my resistance was as fragile as a dream and just as fleeting when I saw the man I came to know as Ramzi.

It wouldn’t have happened, I’ve since convinced myself, if I hadn’t encountered Lady Palmer fretting about the hotel lobby, looking for her daughter. The young woman had disappeared after leaving an afternoon thé dansant, a tiresome trend consisting of dancing and sipping warm weak tea that has spread around the world from Bombay to Manila to Hong Kong by way of the contingent of the smart set. Lady Palmer was a longtime family friend of Lord Marlowe’s and fancied herself his social chaperone after his first wife died. She befriended me, I believe, more out of duty than true friendship. I found her pleasant and unassuming, though her daughter, Flavia, possessed the frivolous manners of her society stepsisters hungry for wicked games, but only if played according to their rules. No wonder Lady Palmer came to my husband numerous times to ask for his assistance in getting her daughter out of trouble without creating a scandal. He always obliged her with the understated elegance I loved about him. I felt that same obligation to help her when she sought me out in Port Said and told me her daughter was missing.

Earlier she had made plans to take the girl on a picturesque tour of the city, she told me, extolling the values of “going native” in a cart drawn by two mules, riding up and down the tree-lined streets past the lighthouse, then the Victorian buildings with purple-red bougainvillea overflowing on the terraces. Flavia refused to go. She assured her mother she’d have a better time at the afternoon tea dance, insisting she’d befriended some British girls she met on the beach visiting from St. Claire’s English School. That was the last time she saw her daughter. When Lady Palmer returned from her city excursion, Flavia’s new friends informed her the girl had left the hotel.

With a man. A tall Egyptian with a charming French accent, they said. Sweeping her away into his arms as if his galabiya, indigo blue robe, was a magic carpet flying around him, the orange-hued imma on his head contrasting with his black hair, the tightly wrapped turban giving him a courtly demeanor. Bidding the British schoolgirls adieu with a grandiose gesture of his bare brown muscular arm, his large ruby ring set in pearls dazzling them, the girls sighed, speculating he must be very rich and very important.

They said his name was Ramzi.

When I asked my British circle of friends about this Ramzi, no one knew much about him, though I watched more than one spectator-pumped miss sigh with a near-rapturous want, as if she’d gladly drop her knickers for a quick poke. I knew I must find him. Was he the souteneur the fortune-teller warned me about, the man who held the key to unlocking the great waves of pleasure I so desperately sought? I shuddered, though in a pleasant manner. I intended to see for myself.

Wrapped in a black curve-smothering tunic with clasps of bright copper and gold placed between my eyes to hold my nose veil in place, I hired a local guide to take me around the port city to places where men wearing dark-colored gandourah sat under the blue-and-white striped awnings of restaurants, playing games and smoking from nargilehs, water pipes. I kept my distance, my heavy cloak trailing over dirty floors rife with crawling creatures, until—

“Asim knows of this man you seek,” my guide said.

“Which man is Asim?” I asked behind my veil, trying to read their faces.

“The man with the dagger fastened with a leather band to his left forearm. He says Ramzi took the girl to his nightclub.”

“Is he sure?”

He nodded. “Yes. The Bar Supplice.”

“Why did he take her there?” I knew the answer before I asked. The French word supplice meant torment.

His mouth twisted in a dirty grin. “In Port Said, one does not ask why. One knows.”

“Take me there. I will pay you well.” I made him an offer, knowing I straddled two worlds here in a culture that judged me as a lesser being than men, but hadn’t I overcome similar prejudice when I, a commoner, married Lord Marlowe? I couldn’t stop now.

“I get into much trouble if Mahmoud sees me bring you there—”

“Mahmoud?”

“Ramzi’s bodyguard. He can snap a man’s neck in two with his hands.” He made a gesture that left me no doubt he’d seen Mahmoud render such a punishment.

I removed the soft georgette from my face as if to remind him I wasn’t like the women of Port Said who lived in a male-imposed fear behind the veil. In a steady voice, I made him another offer. A higher one. He shook his head. I kept raising the ante, trying to persuade him. After all, money meant nothing to me. I’d inherited a vast fortune to spend freely, along with a title, when Lord Marlowe was killed in a motorcar accident. I’ve no doubt he meant for me to indulge in our secret passion after he was gone. A shiver went through me even as I sweated under the heavy robe. This could be the end of my journey to find that passion again. I repeated my offer. The guide’s answer was still no.

I raised the abaya, robe, above my ankles, then my knees, to reveal my white wide-leg trousers, as if my gesture had become a symbol of the shift in my demands that now went beyond asking questions. I must make him understand I wouldn’t go away without an answer. My own curiosity and needs had been replaced by a feeling of dread. I was certain the girl’s life was in danger. No doubt Lady Palmer’s daughter had succumbed to the allure of an exotic man with a charming accent; but after a few whiskeys, I imagined her naked and trembling on her hands and knees in front of him, then lifting his galabiya and taking his cock into her mouth. So young she was, not more than twenty, and inexperienced. What did she know about performing fellatio? Such a delicacy must be savored by a woman.