По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

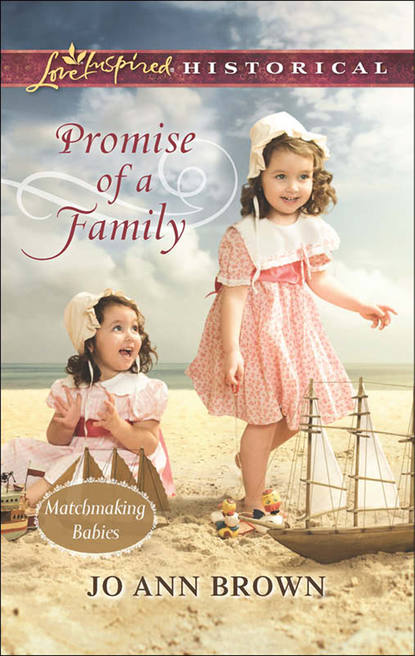

Promise of a Family

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Looking past Gil to the old man holding the baby, she asked, “Is the milk fresh?”

“Aye.” He motioned to a lanky boy standing beside him. “Tell m’lady where ye got the milk, lad.”

He stared at his feet. “At the shop. The lady there said it was delivered this morning. Her assistant poured it out while I was watching, and it smelled as fresh as if it had just come out of the cow.”

“What do you know of milking, boy?” demanded the old man.

“Grew up with cows, I did,” asserted the boy.

To halt the argument before it went further, Susanna said, “If Miss Rowse told you that, it is the truth.” She released the twins’ hands and held out her arms. “May I?”

“Aye,” the old man said gratefully. He settled the baby in her arms, then stood with the help of the lad who had gotten the milk.

As she went toward a row of low boulders, a young woman followed her and asked, “Do you need more milk for the little one, my lady?”

Susanna smiled at the young woman. The hem of her dress and apron were covered with wet sand like Susanna’s. Wisely she had bare feet, so she did not have to deal with shoes caked with heavy sand.

“Are you Peggy who is helping Miss Rowse at the shop?”

She nodded. “Peggy Smith, my lady.” She dipped in a quick curtsy but kept staring at her toes. No doubt, the dark-haired girl wondered what Susanna had heard about her, knowing that news spread quickly in the small town. A newcomer like Peggy would be the talk of Porthlowen until something else caught the gossips’ fancies.

“Thank you for bringing milk for the baby. He or she seems full for now.”

The girl started to say something, then hurried away. Sand sprayed behind her as she sped toward the village.

Behind Susanna, Captain Nesbitt barked an order, but the little boys kept swinging their fists at each other. They managed only to hit him. He put them on the ground, trying to keep them apart.

Gil refused to be parted from the baby. He had trailed Susanna to where she sat on a stone. He watched intently as she placed the baby on her lap. She cooed nonsense words to the baby, but it kept crying with all its power. His lower lip began to tremble, warning he was ready to sob, too.

What is wrong? Lord, help me help this suffering child. Both of them.

With care, she began to undo the blanket that had been wrapped tightly around the baby, keeping it secure and warm. It stank like the other children. Each motion of the blanket seemed to pain the baby—a girl, she discovered—more. She slipped her hand under the long shirt so she could rub the baby’s stomach. It was not hard with colic, but the baby screamed again.

“My baby!” cried Gil, tears oozing out of his eyes.

Her own widened when she raised the shirt and saw a tattered piece of paper attached to the garment with a straight pin. Pink spots on the baby’s chest and stomach showed where the point jabbed her at the slightest motion.

“Oh, you poor dear,” she murmured.

“What is that?” asked Captain Nesbitt.

She looked up, shocked, because she had not heard him approach. His dark coat was stained, and the seam on one shoulder had torn. “The other children?”

“Being watched closely by some of my crew while others shake sand out of the canvas and fit it into the carriage so the seats are not ruined.”

“Thank you,” she said, telling herself she should not be astonished. He had shown his compassion toward the children from the moment she was introduced to him.

“What do you have there?”

“I don’t know.” Careful not to prick the baby again, she drew out the pin and wove it through a corner of her shawl.

He caught the slip of paper before it could fall into the sand. As he scanned it, he clenched his jaw. He handed it back to her.

She struggled with the bad spelling and splotched ink. She guessed it said:

Find loving homes for our children.

Don’t let them work and die in the mines.

Whoever had pinned the note to the baby’s shirt must have been desperate to have that message found.

Beside her, Captain Nesbitt growled something wordless, then said, “Their own families put them in the boat and set them adrift.”

She wanted to deny his words. She could not. Looking from the sleepy baby on her lap and the little boy leaning against her knee back to Captain Nesbitt, she whispered, “How could anyone do that to these sweet children?”

His eyes burned with fervor as he said, “That, my lady, is what I intend to find out.”

Chapter Three (#ulink_9e65954b-8cb1-506f-84cb-bfde2fba66a9)

“Good night, sweet one.” Susanna tucked the blanket around Lucy, who shared a mattress with her twin sister. Both girls were lost in dreams and sucking their thumbs, Lucy her right one and Mollie her left.

The house had been in a hubbub by the time Susanna returned with the six children. She had been sure that Captain Nesbitt would send someone from his crew with her, but he escorted them himself, insisting that he must speak with her father. She was curious what they discussed, but Papa would let her know if he felt it was necessary.

She had turned her attention to tending to the children and trying to restore order in the house. Baricoat had brought her a long list of obvious deficiencies in the nursery, so she decided to keep the children in her rooms until the nursery was safe and comfortable. Busy with making those arrangements, she still had noticed when Captain Nesbitt left.

He had stridden out with purpose and waved aside the offer of the carriage. He glanced over his shoulder only once before he vanished down the long drive to the gate. She had shifted away from the window so he would not see her watching him. Scolding herself for caring what he thought, she hurried back to the myriad decisions she needed to make to ensure the children’s arrival disrupted the household and her family as little as possible.

There was plenty of room in Cothaire for six small children, but somewhere hearts ached with worry. She did not want to imagine what had compelled anyone to put them in a boat and push it out into the waves. Even if the children had been born outside of marriage, every parish had ways of providing for them.

Help us find these children’s families, she prayed over and over. Ease their fears and point us in the right direction.

Two mattresses had been brought into Susanna’s dressing room while the children, except the baby, were offered tea and sandwiches and cake at a table in the kitchen. Mrs. Ford and her kitchen staff had served the youngsters whatever they wished and made sure they ate slowly so they would not sicken. All the children were thin. She wondered how long they had been adrift. Or had they been half starved before they were placed in the boat?

The past year had been difficult for Cornwall. The wheat and barley harvests had been poor and the pilchard season a disaster. The small fish, which the rest of England called sardines, usually provided a ready source of food along the coast. With her father’s permission, Susanna had ordered the Cothaire pantries opened weekly to allow local families to take food. She was unsure if other great houses shared the practice. If not, starvation among the fisherfolk, the farmers and the miners’ families was an ever-present threat.

Straightening, Susanna went to the next mattress, where the three boys were supposed to be asleep, too. Little Gil was rolled up like a hedgehog at one end, but the two older boys, who called themselves Toby and Bertie, were tussling again.

“Enough,” she said in a loud whisper that would not wake the other youngsters. “It is time to sleep.”

Toby, the slight boy with darker hair, whined, “He is taking my spot.”

“He is taking mine.” Blond Bertie glared at the other boy.

She took Toby by the hand and brought him to his feet. Picking up his pillow, she led him to the other mattress, where the twins slept. “Here,” she said.

“But—”

“Sleep here tonight. Soon you will have your own bed.”