По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

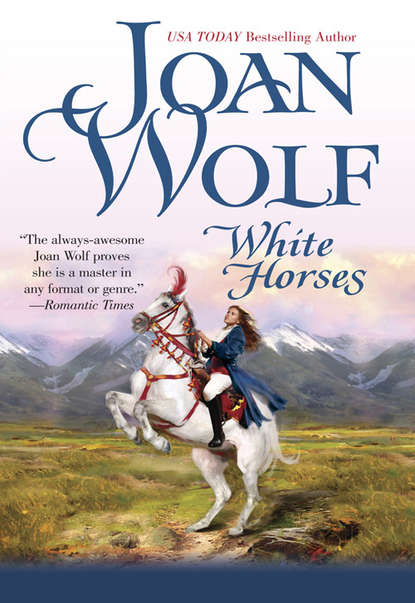

White Horses

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When Gabrielle arose the following morning Leo heard her and sat up in bed. It was still dark.

“We need to be on the road early,” she said. She lit a candle. “I want to be in Amiens by late afternoon. Turn your back so I can get dressed. Then I will get out of your way.”

He obliged and listened to the sounds she made as she got into her clothes. Then she said, “All right.”

He turned to look at her and found her clad in high boots, a brown divided skirt and a white, long-sleeved shirt. “Come downstairs when you are ready and Emma will prepare you breakfast,” she said.

He watched her small, straight, slender back disappear out the door, followed by her dog, then he got up and opened the package of clothing they had bought yesterday. He took out a coarse cotton shirt and regarded it with distaste. It pulled on over the head and had a tie at the neck. He put the shirt on and then his breeches. The shirt was loose and billowed out of his tight breeches.

I must look a sight, he thought ruefully. If Fitz and the others could see me now, how they would laugh.

He pulled on his boots and went down to the kitchen to see what was for breakfast.

Emma was in the kitchen with her dogs when he entered. “Good morning, Leo,” she said cheerfully. “Did you sleep well?”

“Yes, I did,” he replied courteously.

Six dogs looked at him, but none came to sniff him. They remained where they were, curled up on an old quilt under the window.

Emma got up from her chair and went to the counter. “There is coffee and bread and butter,” she said.

He was used to an English breakfast, with eggs and meat, and the proffered bread seemed rather paltry. But, “That will be fine” was all he said, and let her pour him his coffee and add milk in the French way. Then he took his plate and went to the table.

“Where is everyone else?” he asked as he took a long drink of the coffee.

“Getting the wagons ready,” she replied.

“There looked to be quite a few wagons in the field,” he remarked. “How many are in the caravan?”

“Let me think.” She frowned slightly. “I have a wagon, the Robichons have two wagons, and the Martins—they are the tightrope dancers—have one. The Maroni brothers—they are the tumblers—have one, and Sully, our clown, shares a wagon with Paul Gronow, our juggler. Luc Balzac has a wagon. Then there is the bandwagon. That makes eight, I believe. Then we have two more wagons filled with hay and grain, and one for the tents and one for benches. So that makes twelve altogether.”

“That’s not a lot to house a whole circus.”

“The horses are our chief performers, and they get tied behind the wagons.”

The kitchen door opened and Mathieu and Albert came in. They were dressed in trousers, scuffed boots and knitted sweaters. “All that’s left to do is to harness up the horses,” Mathieu said. “Is there more coffee, Emma?”

“Where is your sister?” Leo asked Albert as Emma poured both boys a cup.

“She went back upstairs to pack her clothes.”

“All the costumes are packed, I hope,” Emma said.

Leo decided it was time to discuss their important cargo. “I would like to see the gold, if you please.”

Mathieu scowled. “I can show you where it is,” Albert offered. He stood up and started for the door. Leo followed him.

“Make sure there is no chance of anyone coming in on you, Albert,” Mathieu warned.

“I know,” the boy replied. “Come with me, Leo, and I will show you.”

They exited the kitchen and began to walk across the field to where the wagons were parked in two lines. Most of the wagons had horses picketed next to them. The sun had come up and Leo was conscious of people looking at him curiously as he walked with Albert.

“How long has your sister’s husband been dead?” he asked Albert. “Will people think it’s odd that she has married again?”

“André has been dead for a year and a half,” Albert said. “I don’t think people will be surprised that Gabrielle has remarried, but they will be surprised to find she has married a noncircus man. We will have to find something for you to do so you don’t look too odd.”

“I can help with the horses,” Leo said.

Albert cast him a dubious look. “We’ll see,” he said.

Leo was insulted. Evidently this slight boy didn’t think he was fit to be trusted with circus horses. “I assure you that I am capable of looking after a horse,” he said coldly. “I have been riding since I was four years old.”

Albert said carefully, “You see, our horses are different from the horses you rode, Leo.” By “different” it was clear that he meant “better.”

“And somehow I don’t see you carrying manure, which is what helping out with the horses entails.”

Leo hid his surprise. He hadn’t envisioned himself carrying manure, either, but he was certainly capable of doing so, if necessary. He said grimly, “If you need me to carry manure, then I can do it.”

“Let’s see what Gabrielle says,” Albert said. “She’s the one who doles out the jobs.”

They had reached the first wagon. “This is ours.”

The wagon was painted white, with the words Robichon Cirque Equestre written on its side in red letters. There was a picture of two horses’ heads painted under it.

Leo stopped to look at the picture. “The Lipizzaners?” he asked.

Albert nodded. “The one on the left is Sandi and the other one is Noble.”

The two pictures were clearly painted by one who knew horses.

“It’s a very good painting,” Leo said slowly, leaning in for a closer look. “Who did it?”

“I did,” Albert said.

Leo looked at him. “You have talent.”

A faint flush stained Albert’s cheeks. “I love to paint and draw,” he said.

“Do you have other pictures?” Leo asked.

“Yes. I have pictures of some of the places that we’ve visited. And I have done many pictures of the circus and its horses.”

“I’d like to see them,” Leo said.

The boy’s flush deepened. “I would be happy to show you.”

They had come to the back of the wagon, which had two doors that opened outward. Albert opened the doors and climbed in, followed by Leo.