По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

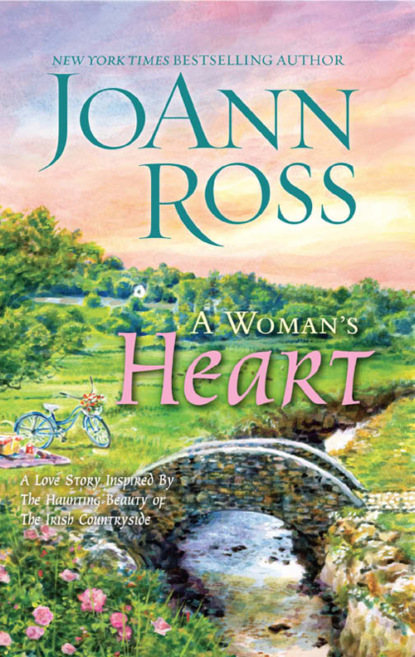

A Woman's Heart

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You won’t be disturbing her at all,” Brady assured him. “Aren’t you a guest? She wouldn’t be having you walk all that way into Castlelough.”

Quinn decided not to mention that he ran longer distances on a daily basis back home.

“Thanks for the suggestion.”

“You’re more than welcome.” Brady looked up from sharpening a yellow pencil with a penknife and beamed his approval. “Enjoy your Sunday drive, now.”

Quinn was on his way to the kitchen when he passed the parlor and saw Fionna sitting in front of the lace-covered window, knitting needles clacking.

“I expect you’ll be wanting a ride into the village to fetch your automobile?” she called out to him.

He paused in the doorway. “Actually I was planning to walk. Brady suggested Nora, but—”

“And isn’t that clever of my son to think of her?” Fionna’s smile, which echoed Brady’s, set internal alarms blaring. “Our Nora’s an excellent driver. And you couldn’t have a better tourist guide.”

“Surely your granddaughter has better things to do than chauffeur me around.”

“Now don’t you be worrying your head about that.” The knitting needles continued to clack with the speed of dueling rapiers in an old Errol Flynn movie. “The family can take up her chores for this one day.” With a brisk nod of her bright red-gold head, Fionna declared the subject closed.

It crossed Quinn’s mind that Nora’s father and grandmother seemed awful damn eager to get the two of them alone together. He wondered idly if they could actually be setting a trap for him, the rich Yank.

It wasn’t as if such schemes hadn’t succeeded before: get an American to marry you so you can get a green card to live legally in the States, then bring over your entire family on the next boat. Or plane, these days, he supposed.

The idea almost made him laugh. Fionna and Brady Joyce could set all the snares they chose. But in this case their prey was far too wary to be captured.

He’d planned to sneak out the kitchen door without being noticed, but found Nora where he’d left her earlier. The O’Sullivans had apparently departed and she’d changed from the dress she’d worn to church into a pair of jeans, a creamy sweater and a white apron.

She was kneading bread. The warm smell of the yeast coupled with the sight of her slender arms elbow deep in the mound of dough made Quinn’s gut twist with something indefinable.

“May I help you?” She glanced up at him with a smile, but her eyes were guarded. As well they should be, Quinn thought grimly. The widow Fitzpatrick was obviously intelligent enough to realize he was way out of her league. “Would you be liking a cup of tea? Or, perhaps, some coffee?”

“Nothing, thanks. I need to go into town to get my car. Brady suggested you’d be able to drive me, but I assured him I can walk.”

“Of course I’ll be taking you.” Again, her smile was pleasant, but self-protective barriers remained firmly in place in her eyes. “If you don’t mind waiting until I get this bread in the pan.”

“I don’t mind at all.” He turned a chair around, straddled it and leaned his arms on the top of the seat back. “I’ve never seen bread being made.”

She laughed at that. “What a deprived life you’ve led, then, Mr. Gallagher.”

“I’m beginning to think you might be right, Mrs. Fitzpatrick.” The movement of her hands pushing at the elastic white dough was both homey and sensual at the same time. “I really hate to intrude on your day.”

“You’re no intrusion at all. I enjoy driving. And it’s a lovely day, after all.”

“Your father said he’d take me if he wasn’t so busy with his ledger book,” Quinn said conversationally.

“Ledger book?” Nora’s hands stilled for a moment, and she glanced at him in surprise. “The farm account book?”

“That’s what it looked like.”

“Well.” She shook her head and began pounding harder at the dough.

“Something wrong?”

“Wrong?” She was refusing to look at him, her voice had taken on a sharp edge, and she’d begun attacking the dough as if she bore it a personal grudge. “What could be wrong with a man tending to business?”

What indeed? Quinn wondered. But something definitely had her ire up. Electricity was practically radiating from every pore.

“Well, that’s done for now.” She turned the dough into two oblong pans, covered them with a cotton dish towel, then brushed her palms together to dust off the flour. “It’ll just take me a few minutes to wash up and—”

“I’ll do that,” a voice offered from the doorway. Both Quinn and Nora turned to see Mary.

“You’re volunteering to do dishes?” Nora’s eyes narrowed. “Saints preserve us,” she said with an exaggerated brogue that reminded Quinn of her father’s. “Ring up Father O’Malley right away, because it’s sure we’re witnessing a miracle.”

“I’ve done dishes before. Lots of times,” Mary countered with a toss of her dark head. “Gran sent me in to finish washing up so you and Mr. Gallagher could leave for the village.”

“And isn’t that thoughtful of your grandmother,” Nora said dryly. She washed the remaining bits of dough off her hands beneath the tap, dried them on her apron, then took it off and hung it on a wooden hook on the wall. “If you’re ready, then, Mr. Gallagher.” After plucking a set of keys from another hook, she walked out the kitchen door, leaving Quinn to follow.

“What the hell is that?” He stared at the huge garishly painted old Caddy sitting in the driveway where earlier red-feathered chickens had scratched.

Nora arched a brow. “Are you telling me you’ve never seen a miracle-mobile, Mr. Gallagher?”

“This is a first. Is it yours?” He assured himself that he’d survived far worse in his lifetime than being seen by any of the crew in what looked like an amateur artist’s rendition of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

“Don’t worry, it’s Fionna’s. Mine is the blue one parked behind it. We fetched it from the pub after mass this morning.”

Thank God. “Nice car,” he murmured.

Nora laughed in a way that told him she knew exactly how relieved he was feeling. “Thank you. It’s a wee bit boring compared to Fionna’s. But I like it.”

The car, like most he’d seen in Ireland, was a compact sedan that could probably fit into the rear of the Chevy Suburban parked next to the Porsche in his three-car garage back in Monterey.

“I really am sorry to inconvenience you this way,” he said into the well of strained silence surrounding them as they drove through the rolling green hills. It was obvious that her brief humor over his reaction to her grandmother’s colorful Cadillac had faded, leaving her still upset about something.

“It’s no inconvenience,” Nora snapped. Then, as if realizing how brisk she’d sounded, she sighed and rubbed at her temple, as if trying to ward off a headache. “I’m sorry. Truly I don’t mind driving you into the village, Mr. Gallagher. It’s just that I’m a little put out at my family at the moment.”

“For throwing us together.”

She shot him a surprised look. “You knew that’s what they were doing?”

He watched the color—like wild primroses—rise in her cheeks, tried to remember the last time he’d been with a woman capable of blushing and came up blank. Even as he reminded himself that innocence held no appeal, Quinn found the rosy hue enticing.

“It was pretty obvious.”

“I’m sorry.” She combed a not very steady hand through her riot of curls. In the midday light her hair glowed like a burning bush. Her wrists were narrow, her fingers slender, her short nails unlacquered, once again bringing to mind a nun. A sensible man would give her a wide berth. Quinn reminded himself he’d always considered himself a sensible man.

“It’s not right that you should have to deal with their foolish matchmaking schemes while you’re a paying guest.”

“I’ve survived worse.”