По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

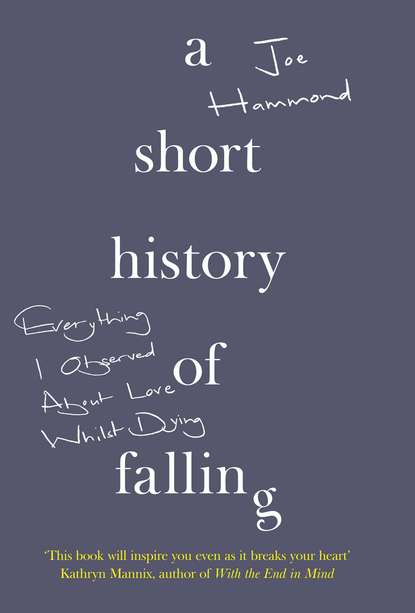

A Short History of Falling: Everything I Observed About Love Whilst Dying

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My first fall was when I was walking Tom to school. We had joined with several mums and their children and it was a cheerful occasion. I made my way to the edge of the pavement to widen our group so that I could chat alongside what was now a phalanx of mums. But as I put my right foot down, I felt only the very edge of the kerb. I’d expected more underfoot. And the rest of my foot fell away from the group. Not off the edge of a cliff, off the edge of a kerb, but somehow I kept falling. There was no correction from either leg, as if each were too polite to be the first to move. So the whole structure of me went down. It all landed between two parked cars. About five or six children looked over me, including Tom, and a number of the mums. Something about the choreography perplexed – I think we all felt that. After the briefest of moments, most of us started laughing. And then I got up and we laughed some more. We laughed about it again when our walks next coincided.

But Tom laughed the least. He wasn’t particularly upset; he just didn’t find it funny. He’s logged quite a few falls since then. Several weeks ago he was with a friend as she listened to an account of her aunt’s recent fall and then remarked that adults don’t do such things. My son corrected her immediately. It was a factually incorrect statement, and he is good at spotting those.

*

I next fell while trying to do an impression of a pop-up toaster. This was some months later. Actually, there had been other falls in the intervening period, but nothing calamitous. Nothing I remember. By this time we were living in Portugal, where the tiled floors are so shiny that I can’t think of anywhere less suitable for a man with my predisposition towards falling. And this was just part of the adventure. A new life on shiny floors. On this occasion I fell and slammed the back of my head against a radiator. Tom and Jimmy, who was then just over a year old, were sitting on Tom’s bed wrapped in towels after an evening bath. Tom had just correctly identified my washing machine and there had been other white goods, as well as a vacuum cleaner. With the toaster, I keeled over because my left leg achieved the elevation my right one couldn’t. It was a buckled-cartwheel move, and when my head made impact it was the deep vibrating sound from the pipes that shocked us all. I lay back with my head wedged uncomfortably forwards against the steel pillow. After a few moments, Jimmy started crying; then Tom. I looked over at them. Their tears. Their crumpled faces. And a nasally sound like two interlinked air-raid sirens being squeezed out through their ears.

There’s so much more indignity in failed silliness. The thought of no longer being the clown brings me as close as anything to feeling defeated. A lot rests on being able to impersonate a toaster. I don’t think I’ve ever wanted to spend more than five minutes with anyone who isn’t in some way capable of being a clown. And my feelings of loss are at their most profound when these opportunities evade me. If I can’t brush my teeth in the style of a camel. Or getting dressed in the mornings and no longer being able to chuck my discarded pyjamas at my children.

I’ve noticed that nothing can trigger tearfulness quite like an unexpected sound. This was the case with my toaster and the deep clang of the radiator, but also with the time I wrote off the kitchen cutlery drawer. I’d grown weaker, but was reluctant to give up my role as house cook. In the kitchen I needed to hold on to the counter to keep myself upright. So it was all quite sloppy; a little desperate. I’d chop an onion by throwing a knife at it or chuck a used spoon at the sink from twenty feet away. On this occasion my energy was particularly low. We had guests and I should have asked for help. I remember I didn’t bother counting the cutlery. I just shovelled it up and left the drawer open, then spun around towards the dining table. I shouldn’t have been spinning. I shouldn’t have been manoeuvring in such a casual way. But I doled out the correct cutlery at the table and spun back towards the drawer with the spares, catching the left toe of my rubber trainers on the shiny tiled floor and my right spastic foot on the heel of my static left ankle. Having reached tipping point, there wasn’t a chance my legs could save me. By this stage of the disease, rather than legs, my upper body was being supported by a creaky twin-set of large Victorian steel stanchions. I knew I was falling. It’s passive knowledge. Knowing it’s about to happen; knowing I can’t prevent it. In a cartoon, I would be whistling at this point, or checking a wristwatch. But actually, in that moment, I was gauging my total ‘arms outstretched’ length, my distance to the cutlery tray, the fixed position of my feet, and had calculated that my hands would become parallel with the cutlery tray at the point at which my falling body would reach an angle of thirty-five degrees from the floor. And I had judged it well: that’s exactly where my hands were. But I had not allowed for the velocity with which my hands would be travelling through the air, and this was considerable. My upper limbs crashed through the open drawer before I could reasonably subdivide into forks, knives and spoons, bringing the drawer and its contents down with me, in much the same way that simulated films show the collision of an asteroid into Earth, bringing an end to the age of dinosaurs.

*

My role as house cook began sixteen years ago. I’d known Gill a week, so we weren’t even living together by this point. I was lingering outside her kitchen, trying to catch sight of her as she prepared a meal. I didn’t know what to do and I was a little nervous. A little expectant. I heard clattering sounds and moved to take up a better vantage point. I remember the excitement of then seeing Gill through the frame of the doorway. She was holding a tin of tuna, trying to get the contents out. She was thrusting it downwards, the way a person might try to get some very stiff ketchup from a bottle, the way someone would do this when they don’t know the technique of slapping the base of the bottle with the palm of the hand. She was trying so hard. And I have always remembered the repetitions of the despairing downward plunge of her arm. That repeated, forlorn, hopeless, futile, beguiling, beautiful movement of her arm through the air.

*

It’s hard to live the losses moment to moment, accepting them as they arise, dispensing with pieces of the self fluently like a bag of birdseed strewn into a flock of pigeons. Lying on my back on the shiny tiled floor, I was struck by the amount of metal and detritus that can be loaded into one cutlery drawer. I was turning as I hit the drawer, so my hands and wrists connected side-on to the open drawer and the impact turned me completely. I couldn’t necessarily see what was lying all around me, but the sound of falling metal seemed to continue like hail on a skylight. And I lay, arms outstretched, on this sea of steel and crud. A friend and her sister were staying with us, and each got up and took my arms, raising me to a marginally more dignified seated position. Directly in front of me were Tom and Jimmy, standing side by side. Three foot tall and two foot tall. Their lips were beginning to agitate, like four pink caterpillars rippling across a leaf. Sitting on my bum amidst the debris, I watched as their faces crumpled and they again began squeezing air-raid sirens out through their ears. Once they had levered me up, the two sisters began gathering in all the items. It was a job I desperately wanted. I wanted to be down there, on my knees. Putting it all back together again. The spoons in one place, the forks, the knives. The masher, the crusher, the bashers, the smashers. The togs, the bottle tops, the skewers, the openers. And then a dustpan and brush for all the accumulated dust and dirt.

*

From an early age I dreamt of falling. For many years, this simple dream included nothing more than a matchstick or a marble or something small like that. It was just me and these little bits and pieces suspended in space. It was something like the very beautiful children’s television programme from the 1980s called Button Moon, which told the story of Mr Spoon and his friends in a bits and pieces universe. My own version wasn’t quite as charming. There was no ground or environment – just these items – and in the dream I would be concentrating on these little things. My hands were there and in this dream my job existed to make sure nothing fell. And this really was the crux of it – that nothing must fall. Because if it did, everything would end.

I used to listen to my parents fighting at night. It was dark outside. And if you’re an older child, you turn your music up, or you open your door and shout down the stairs, slamming the door back shut behind you. But if you’re young – or very young – nothing seems separate from who you are. Sounds settle on the skin and are then absorbed, as if they are your own, as if these problems are your own.

I had this dream in largely the same form, for many years. Always the same task – to keep the world in place. I think the pressure was something like a bomb-disposal expert might feel if they were somehow forced to experience their job as a child. And, of course, within this dream something would always fall and I would wake with the certain knowledge that not a bit of the world remained.

*

As my legs began to weaken, and my right spastic leg began to stiffen, I was excited to find that I could improve my balance by walking around with a book on my head. Tom had a Paddington Bear book that worked best. It was hard and heavy and square and I seemed more conscious of my movement with this book. Less likely to fall. It was the story of Paddington’s journey from Darkest Peru, his arrival at Paddington station, and his early home life with Mr and Mrs Brown. I made this discovery about a month or so following my diagnosis. At around this time my arms began a spontaneous adaptation to the heaviness in my legs. I widened my gait and began purposefully reaching out with my arms, and breathing out with each movement. It was loosely inspired by a session or two of t’ai chi that I once did, but it felt like my creation. Or an evolution, perhaps, towards life as an anthropod.

I cherished this time. I felt more aware of my body than at any other time in my life. I wanted to feel my body and be in my body because I knew I was losing it. I think about this time and often wonder what would have developed had I not caught a leg on the strap of a bag I’d left on the bedroom floor. Part of me wishes I’d decided to make impact with my face, not my shoulder, because I later decided that the disablement of my shoulder accelerated certain aspects of this disease. But I think all this fall did was to create a kink in the line of my body’s development. The perception of acceleration, maybe some actual acceleration, but not much. The abrupt end to this fertile period helped me to mythologize my short life as an insect. That’s all.

Because the truth is that I was actually declining through this period. I just enjoyed the thought that I wasn’t. I think the fall ended one kind of hope, but it didn’t end all kinds of hope. The creative life gets harder and darker and more real. But life is not worse than it was before. It doesn’t have less value. It’s not less interesting. Not at all. As I get weaker, less a part of this world, or less a part of what I love, less a part of my family’s life, I can perceive its edges with fantastic clarity. I can lie against it, lolling my arm over the edge, running my fingers around the rim. And this is where I am.

*

I might now notice that I haven’t fallen for a while, rather than that I have fallen. This normalization is just taking shape. I had one of these quotidian falls last week. As I was heading out of the kitchen, I caught my sandal in the indentation of the grouting between the floor tiles. My wrists were attached to crutches so that, falling through the door, my body and both arms behaved like three portly figures bustling to be the first out. I was aware of a lot of jostling between these separate components of my body. The momentum took my torso through ahead of the other two fat fellows, with my arms pinned back behind as they followed. As these three oafs who comprised my body clattered through the doorway, what landed first was my chin. And because of the order of my body, my shoulders splayed out and my palms landed with a splat on either side. One crutch was still painfully attached to my wrist, cuffing me to the ground. And my body transmitted to me the physical impression that I had been pinned to the floor by an arresting officer. I didn’t initially attempt to move. I wasn’t particularly hurt; it was more the feeling of profound dismay at having to work out a way to get up from the floor.

Having previously described the siren sounds of my children after they witnessed one of my falls, this fall provided further evidence of the transition along the scale from horror to tedium. There was a brief sound of upset being squeezed out through Jimmy’s ears, but nothing like the previous episodes and nothing from Tom. They had seen it all before. Daddy had now been seen on the floor on a number of occasions, so the sound on this occasion was something like that brief attention-seeking pulse from a police siren that makes you wonder why they bothered. I think Jimmy soon thought better of it and he continued emptying the recycling out from its various containers. Gill came to help, but I told her I was OK for the moment and, dribbling into the carpet, suggested she finish grilling the fish fingers. Tom stepped over me on his way up the stairs. I could hear supper being plated up and I wanted to stay put – perhaps for ever. I was seriously considering the possibility. And nothing about that thought felt in any way abnormal.

*

I now spend a lot of time in my pants and people come and go. It’s getting harder to put my clothes on and the heating here is quite good. As I write this, I’m in my pants, and I’m looking down at my T-shirt which displays the remains of two splodges of the beetroot and squash soup I had for lunch. A lot of me is not as decorous as it once was and it’s in this unvarnished state that I now tend to find myself, groaning on the floor, after the latest fall.

Having fallen, it’s now impossible for me to get myself back up. That’s been the case for months, but now Gill and I can’t quite manage it together. The most recent example resulted in quite a lot of pain and the unfortunate reprisal of my recently healed rotator-cuff injury. On this occasion, Gill was the first to arrive and I was able to roll over on to my back to have the usual conversation about whether I was or wasn’t OK. I spent a minute or two being aware of the furrows on Gill’s brow, but then Jimmy swung in through the door. He was smiling broadly and, having not actually seen me fall, appeared simply tickled by the experience of looking down at me.

A visiting friend of ours was the last to arrive. I suppose I mention all this because, with this particular episode, I’m partly writing about dignity and how I just don’t bother with it any more. Attending to my dignity would take too long and would consume a vast amount of Gill’s time. Behind every sponged and smartly dressed disabled person has to be someone else’s considerable and uncredited commitment.

It took us a few minutes, but the mechanics of raising me up were extremely effective. I’m no engineer so I cannot explain the considerable biomechanical benefit of a single hand placed lightly under my bottom. Under normal conditions I struggle to raise myself from a chair but, with a hand inserted just under my bum, exerting marginal upward pressure, I seem to experience very little upward difficulty. On this occasion we were trying to raise me up from the floor but with the compensation of six hands. I found it particularly affecting that two of them belonged to Jimmy – the boy I should be cradling in my big Daddy arms. My wife, my son, a friend – all managing with my near dead weight. I could never previously have conceived of six hands seeking upward traction from my bottom. But the operation worked. In yesterday’s pants and a dirty T-shirt, I’d made it to sitting – on the edge of the bed – relieved and looking out at my trio of helpers.

*

For almost six months we’d been living on the side of a mountain in rural central Portugal, and then I was diagnosed and we fell all the way down to the bottom. We fell through the pines and the eucalyptus, bumping and clattering against the trunks, brushing through the foliage. We cartwheeled and bounced and slipped – an eighteen-month-old baby, a six-year-old boy and a mum and dad. And it was remarkable that we fell a mile downwards from high up on the mountainside, with the speed of falling objects, but sustained no external injuries – no cuts or grazes. Nothing visible. Everything that hurt was on the inside – the disappointment and the shock and the sadness.

It had been Gill’s idea to come to Portugal. She had been on maternity leave with Jimmy and dreamt up the idea, and we carried through with it. Our flat had been rented out and we were experimenting with a different kind of living. Tom had not enjoyed his start to school life in the UK but now found himself in a tiny bilingual school surrounded by cherry trees, where he spent half his day constructing shelters from old tractor tyres and mud and fallen masonry and discarded timber.

And Gill and I spent our days together in the sun, learning a new language and eating the oranges and cabbages and potatoes that neighbours would leave on our doorstep. And I don’t know how long this life would have gone on for, but I do know, if my diagnosis had been for something sweeter, something fixable, that our journey home to the UK would have been slower – not off the side of a precipice, with the rocks, the stones and the blood-red earth flashing by.

*

I had a moment yesterday when my fingers went reaching for the finial on the banister at the first landing. I looked at my fingers. They were playing a little piano melody in the air. I could feel the slightest sense that my body had moved backwards, rather than forwards. That my hand was doing the opposite of reaching; it was withdrawing. And that this worried me. It was only a faint sensation at this point. The very gentle transitive feeling that a treetop must feel just after the axe has finished its work on the trunk. A subtle movement at first but with full knowledge of the carnage that will follow. It’s the worst kind of terror, the one that begins with such gentility. Knowing what it means; what it would mean for my body. The steepness of the gradient behind me and the hardness of its edges. The damage I would do to my limbs if I were to fall back in that moment. Falling back and needing to take it. The quiet minutes and hours and years of the falling moment. And the thoughts of my wife as she would come running. What all this would mean. Of lives disturbed. By a set of fingers flailing short.

This is a special subcategory of falls – perhaps the worst kind – because they linger and they haunt, they spill and they drift. These are the almost falls – the ones that never happen; the ones that nearly happen. The moment of knowing a fall is happening. Not fearing it. Knowing it. Even if that moment is fractional, and then snapping out of that space. It’s the waterboarding equivalent of falling, because it feels like it’s happening but it’s not. The heart turns inside out like a rubber cup and then pings back into shape. It’s time travel, or two parallel moments coexisting: the disastrous one and the banal one, with thoughts rattling helplessly between them like a pebble in a bucket. The finial was out of reach, but the banister rails weren’t. I never forget the almost falls. Not the bad ones.

One pebble has been rattling around for the last nine years, getting more clattery with each recollection. I was on a path on the edge of a ravine. I must have stopped for something. A view? Maybe I needed a piss. Gill was ahead. I could see her disappearing as she traversed the sharp cliff along a loose, flinty path. We were trekking on the Indian side of the Himalayas, without a guide. We were alone. And as I skipped forward to catch up, my toe caught a rock and my two insteps collided. After a stumble forwards, the thick sole of my right boot skidded flat and I came to a stop. I was on my own in the silence. Gill was out of view, with the precipice just ahead. I thought of the degrees by which falls can happen: the strength or slightness of the connection that one toecap might make with one heel, in the process of stumbling and clattering. And how close I came to a more prolonged stumble, and then to nothing, to disappearing over the edge, in the silence, out of view. Imagining the experience of Gill as she stepped back on herself into a mystery. To an empty path. It’s the silence of that moment that concentrates this memory. The fitting stage that it was for an ending. The intimation of an ending, even though it wasn’t.

Every thought I have had about that moment has been more profound than the one I had at the time. I shook it off, but it has stayed with me and has grown in the dark with each recollection. I didn’t mention it to Gill when it happened. I just trotted on and caught up. Because nothing actually happened – nothing that I felt I could communicate.

I’m falling now. But this time it is real. Unlike you, perhaps, I know I am dying. And because of that I fear it less.

The Body (#ulink_b564740d-d812-5c92-8f7a-f6062904d253)

As I progress down the upstairs landing, holding on to my four-wheel disability rollator, I invariably glance through the open door of the bathroom. It’s become a pattern. Glancing through the door at the metallic frame that holds my raised plastic disability toilet seat. This momentary experience reminds me of the times in my life when I’ve walked past specialist disability shops, gazing absently at all the unlikely paraphernalia from other people’s lives. This world of experience in one shop. And this is what it feels like, seeing this contraption installed around my toilet. It’s other people’s lives; not my own. But each time I remember that it is mine, and that’s quite shocking.

I think I feel the same level of original shock on every occasion. And these are largely the same feelings that I have about every disability item I own: the cone-shaped device for putting on my socks, the grabbing and reaching implements, the rails, the splint, the stroller, Dr Seuss’s fantastical self-washing wires and brushes. New items arrive almost daily and I am unexpectedly becoming the curator of the Museum of my own Decline. How did this happen? Because it wasn’t so long ago that I was walking past these shops. I was on the pavement looking in. And now I am inside.

*

If you’re disabled, London beggars don’t ask you for money. They don’t even make eye contact. I discovered this whilst visiting the UK at Christmas, travelling through London on my own. This was a few months before we had to move back permanently, and I was being disabled all by myself. I must have seemed quite unsteady because it was my first experience as the recipient of help from strangers. I found this exciting. I don’t feel excitement any more. But at that time it was exhilarating in the way that all transportive experiences can be exhilarating. Like an acting student with a begging bowl or a celebrity in a fat suit. Except that it was me. The most complete version of me that I would ever be.

I changed trains at East Croydon and deliberately trailed a woman with a crutch who had a spastic leg like mine. I sat quite near her but realized she was much younger, with MS. Then I felt like an older man stalking a younger woman, which I briefly was. I gravitate towards people with a bad leg like me. At Three Bridges station there was a man of about my age with an even slower walk than me. He was dressed smartly and clearly trying to sustain some kind of job. I was coming from the other direction and had enough time to become excited by the way his leg was swaying wildly – just like mine. It was rush hour. Not an easy time to be thrashing your leg around. I wanted to wave or to say something; or communicate to my brother with an upward turn of my eyebrows. And because we were heading in opposite directions I knew our unacknowledged time together would be fleeting. He needed help, from crutches at least, but he had nothing. I was impressed by his lack of speed. I should have been going a little slower. Or I should have stopped to think, but I ended up doing the opposite. I picked up speed and felt momentarily jaunty. It’s what I must have wanted. I was racing along. And that was it; the moment for connection was gone.

He’s not the first person I’ve picked out, wondering whether he or she is the same as me. Wanting to ask. I fabricated a notion that this man’s symptoms might have been further on than mine. Perhaps he had been slow to refer himself, and was soldiering on. A man who was continuing to work in the face of considerable difficulty – wondering why his foot wouldn’t lift off the ground. Wondering why he was always toppling over like an old wet tree in the rain. And waiting for it all to stop, for the body to return, to heal, because that is what the body does.

I don’t think I’m looking for my comrades any more. Not with quite that expectation. Or with that sense of shocking newness I want to share. But still, when I’m with a friendly physio or occupational therapist, I often end up asking about their other patients. I must want to find someone like me. Someone out there with children who is where I am with this disease. Someone out there who is writing about it. Wanting it to be OK. Willing it to be OK. I want to meet this person.

*

It’s shocking to me that I have a spastic leg. I’m struck by its arcing trajectory, its banana-shaped inefficiency, and by the sticks I use to compensate for it. And by the wheelchair I will one day be consigned to, the toileting aids that await me, disfigurement, the premature ageing. These are all shocking to me; I’m calm about it, but still shocked. I’m calmly shocked.

All my life I’ve convinced myself that I have a remarkably striking physical appearance. Unfortunately, I have been capable of believing that almost anything about me, or almost anything I’ve done, might be remarkably brilliant. I have been afflicted by this delusion for my entire life. There’s nothing unusual about this. It’s just the dreariness of narcissism. Only the route towards narcissism is unique. The real stuff. The narcissism itself, the affliction, is dull, boring and predictable. And as with all narcissism, mine has an obverse side which is equally true and equally present: the unrelenting conviction that when I’m not being remarkably clever and beautiful, I’m being remarkably stupid and ugly.

But now I’m living with a concept that is neither. It’s not life at the end of either of these two extremes. It’s not even on the same linear scale. These days I’m preoccupied by the surprises in my life. The way the body reminds me of myself. The saliva I’m now collecting in my mouth. It’s this. It’s all the tiny signals I experience. The not swallowing. The lagoons beneath my tongue. These pools of saliva don’t interest the narcissist in me. In the presence of such novel details I’ve finally found a way to bore him. With my actual body. The volumes of swallowed juices that sluice away like the downpipe from a toilet stack. Sometimes when I inhale they inadvertently skim backwards with a splutter and a choke. Or, if I’m lying on my front, a small amount disappears over the curve of my bottom lip. Just a little for now, over the side of the bed. Just a tiny stream from a toy teapot. A darkened dot on the carpet. Everything starts as something small. There are no shocks. This is a gentle kind of devastation.

When I was a much younger man I spent a year or so not being narcissistic. I had found God, briefly. I knew him for a year. He loved me and I loved him and my narcissism ebbed away. I felt the tension in my body release. I felt my 25-year-old body open up, after many years of tightness. When I no longer felt I knew him, my narcissism returned. My body closed again, as if a season had passed. This sounds glib, but it’s the truth. And even though I lost hold of what I had found, I don’t think a person ever completely loses what they have had. I’d lived with a level of shock and confusion my entire life, but something had been lifted that was never completely pushed back down again.

And now, being a man with a spastic leg, finding myself being wheeled through an airport in a wheelchair, as I was earlier today, I realize this is the culmination. It’s finishing something, finally and decisively. I’m a man with a disability. My body is the truth now and it’s saving me from myself. I have all these losses, and feel a kind of freedom in that. With each awkward, spasmodic movement, or the difficulty I have wiping my own bottom, or with the slur developing in my voice, the narcissist recedes. There’s nothing for him here. Not any more. It’s death to him. The phoney.