По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

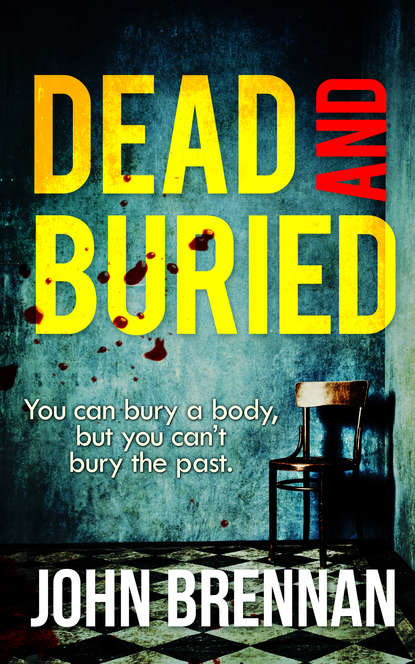

Dead And Buried

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What?’

‘That thing. With your foot. Every time I do anything your right foot jerks like you’re slamming on a brake pedal. I can see it out of the corner of my eye. It’s making me nervous.’

Conor smiled. He hadn’t even known he was doing it. ‘I’m sorry. You’re doing great.’

‘I haven’t even hit anyone yet…’

‘True, true. But is that only because the kerbs keep getting in the way?’

‘If you don’t shut up I’ll drive us into the river.’

‘You wouldn’t…’ he began – then broke off suddenly. A black car in the rearview – that was what it was.

Ella sighed and slapped one hand on the wheel. ‘God, Dad, what is it now?’

‘Right here,’ he said sharply, pointing at a turning that led back into the estate. Ella indicated, braked – they had to wait for three oncoming cars to pass before they could make the turn. The black car followed. That damn woman. Didn’t she ever let up?

‘You okay, Dad?’

Conor forced a grin. ‘Yeah, of course. Sure. You know I love white-knuckle rides. Left here – then a right. Ah, that’s only an amber – go straight on.’

It isn’t sacred ground, for Christ’s sake, a part of him insisted. It’s a residential estate in Sydenham. And Galloway can go where she likes – she’s the law.

He found himself holding his breath as Ella rounded a bend and the poplars at the end of Rembrandt Close came into view. In the rearview, the black car followed – then slowed, and turned, jerked through a hasty three-point-turn – even the car looked somehow angry – and drove away.

Conor breathed out heavily as Ella drew up outside number eight, mounted the kerb, ran over a tub of geraniums, and stalled. There was a moment’s silence.

‘So?’ Ella said, throwing up her hands.

‘Mm?’

‘Did I pass?’

Conor smiled.

‘One or two minor faults,’ he shrugged, opening the door, ‘but I think we’ll get there in the end.’

Christine was in the kitchen when Conor followed Ella inside. She was sitting at the pine table, sifting through some students’ papers. She didn’t look up. Conor paused uncertainly in the hall. The wallpaper was the same, the carpet was the same. But something was different. More flowers, in more vases, for one thing – and fewer pairs of boots and grubby running shoes cluttering up the floor. No jackets slung over the banister.

‘Coffee, right, Dad? Two sugars?’

Ella was already breezily taking down coffee cups from the cupboard, filling the kettle, rattling in the cutlery drawer for a teaspoon.

Christine finally noticed her ex-husband hovering in the doorway. She smiled – a tired smile, but it’d do for Conor.

‘Hello, Con,’ Christine said – a little warily, it seemed.

‘Hi.’

He moved into the kitchen and leaned with an elbow on the worktop, then thought that might be presumptuous and straightened again. Christine went back to sorting her papers. She taught English to immigrant workers at a college out on Limerick Road – Conor guessed that was how she’d met Simon.

‘How’s work?’ he tried.

Christine sat back in her chair and blew out a breath. With a smile she gestured at the spread papers and said, ‘Never-ending.’

‘She works too hard.’ Ella set down one cup of coffee on the table at Christine’s elbow and another – Conor’s – just opposite. His old place at the table. Ella did it like it meant nothing, but from the way her glance flickered from her mother to her father it was obvious it meant more to her than that.

Conor, taking the chair Ella indicated, hoped it didn’t mean too much. They’d hurt Ella once – that is, he had.

Ella’s mobile buzzed. ‘Oop!’ She checked the screen and her eyes widened. You little actress, Conor thought wryly. ‘Kieran! Oh, gosh, I promised I’d ring him. Sorry – got to go. Thanks for the lesson, Dad.’ She pecked his cheek. ‘See you soon.’

‘S’long, sweetheart.’

The kitchen door banged behind her. Conor, shifting uncomfortably in his chair, said, ‘I’ll finish my coffee and be off. I can see you’re busy.’

‘God, I’m always busy,’ Christine smiled. She rolled back the sleeves of her faded blue sweatshirt and stretched her arms wearily. ‘A coffee-break won’t hurt.’

‘Was Ella right? Have you been overdoing it?’

‘Someone has to do the work.’

The language school, she said, was a madhouse – ‘everything done on the hoof, everything improvised, nothing planned’. Every day was like turning up knowing you’ve got to go up on stage, but there’s no script, and you don’t know who you’ll be acting with, or who’ll be in the audience, or whether there’ll be an audience.

‘These are people,’ she said, ‘that don’t know where they’ll be in a month’s time, a week’s time, even.’ She smiled. ‘It teaches you your business, I’ll give it that. In my first six weeks I learned more about teaching than I ever did at college. It’s a lot of responsibility.’

Conor remembered how proud he’d been when the language school down on Ulsterville had opened. Chris had teamed up with a couple of the girls she’d graduated with – they’d all sunk their savings into it, plus whatever they could beg from the banks or scrape up in government grants. They’d never been short of students. Just short of cash.

Tammy, one of Chris’s partners in the business, was half-Mandarin: they’d started out expecting students from Donegal Pass, Chinatown, and from the Asian communities in Upper Bann or Foyle.

‘But now,’ Christine said, ‘Bulgarian, Serbian, Romanian.’ She counted them off on her fingers. ‘Russian, Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian. Then Arabic, Kurdish, Pashto, Bengali, Tamil…’ She laughed, shook her head. ‘Are you up and running at the practice yet?’ she asked.

‘Getting there.’ Conor smiled wryly. ‘Dermot’s got one more week. Not sure he’s ready to go, though.’

‘You can’t blame him,’ Christine said sympathetically. ‘It’s been his life, hasn’t it?’

Dermot Kirk and Donald Riordan had run the practice for years. They were good vets, both of them – knew every farm and farmer in Northern Ireland, hell, pretty much every damn animal – and they knew one another, too: partners in the practice since the sixties, they might’ve passed for brothers, or twins, even.

But Riordan had died a few years back. Heart failure. Dermot had written to Conor in Kenya to tell him; the handwriting had been spidery, frail, wayward. Dermot had the steady hands of an expert surgeon, even now he was, what, sixty-five, seventy? – but they’d trembled when he wrote that letter.

Chris had always got on with Dermot. He was a prickly old lad with a face like a bag of spanners but there was something in him that Christine responded to – gentleness, maybe. Mercy. Strength. On his better days Conor sometimes thought that maybe she saw the same things in him.

‘I’ll end up having to run the old bugger out of the place at the point of a gelding knife,’ Conor said, and Christine laughed.

For a second it felt like it used to between the two of them. But, Conor told himself, it’s not – and you’ve no right to sit here acting the man of the house and pretending that it is.

‘Simon all right?’ he forced himself to ask.

Christine gave him a look that pinned him to his seat. ‘Why do you say that?’