По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

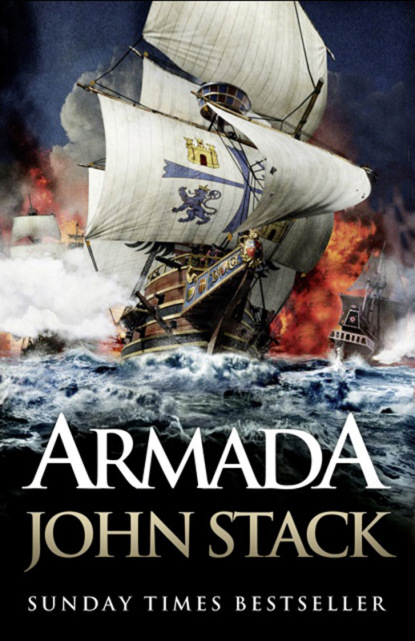

Armada

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Over the roar of the wind Robert heard, ‘Report, Mister Varian,’ and he turned to see the captain approach.

‘As before, Captain,’ Robert shouted, his hand cupped over the side of his mouth, ‘wind holding south-west, at least thirty knots. I estimate we are forty-five degrees north, over a hundred miles north-north-east of Cape Finisterre, in the Bay of Biscay.’

Robert could not be sure, for it had been impossible to accurately sight the sun at noon over the previous days to determine their exact latitude, while their longitude could only be determined by dead reckoning, an inaccurate task in such a storm. Captain Morgan nodded regardless, trusting his new master.

‘Any other ships in sight?’ he asked, wiping the airborne spray from his face.

Robert glanced at the lookout at the top of the main mast. His head was darting from side to side, covering the points of the ship but he showed no signs of having sighted any other sail.

‘Nothing,’ Robert shouted. ‘Not since the Dreadnought near dawn. We lost sight of her over three hours ago.’

‘And no sign of survivors from the Deer?’ Morgan asked, his voice betraying his anticipation of the answer even as Robert shook his head.

The Deer, a pinnace, had been lost early in the storm, the smaller vessel floundering under the first savage blows as the front overtook the English fleet. Robert, with the rest of the crew of the Retribution, had observed her sinking, the ship slipping beneath the waves not four hundred yards off the starboard beam. Many of the men on board the Retribution had called out in vain to the few survivors they could see in the water, urging them to make for the galleon or to cling on to whatever debris they could find, to hold fast until the storm abated and the longboat of the Retribution could be launched to rescue them. But the wind had never eased, had never backed off, and in desperation they had seen the men disappear one by one, some carried away by the tempest, while others slipped beneath the torrid surface of the sea.

Movement at the top of the main mast caught Robert’s eye and he looked up to see the lookout shouting down to the quarterdeck. His cry of alarm was lost in the wind but the direction of his arm pointed out the danger. Robert slipped his safety line and ran up to the poop deck to stare out over the aft gunwale. The approaching wave filled his vision, its wind torn crest standing twice as tall as the waves before it.

‘Look out for’ard,’ he roared in warning to the crew and he jumped back down to the quarterdeck. The wave crashed over the starboard quarter. A wall of water surged over the ship, engulfing the men on the main deck, carrying one of them over the side. The stern of the Retribution swung to port under the force of the wave, bringing her broadside to the storm. The main deck was awash and the crew desperately clawed at the timbers as the sea tried to claim them.

The storm tops’ls lost their shape and the halyard of a brace to the main tops’l yard snapped under the unequal stress of the wind, its block and tackle swinging wildly across the quarterdeck, striking one man on the side of the head, killing him instantly. The yard swung around the mainmast, twisting the sail out of shape and the wind spilled from it, rendering it useless.

‘Main tops’l ho!’ Robert shouted even as Shaw, the boatswain, ordered two men, Ellis and Foster, aloft, following closely on their heels as they clambered up the shrouds. ‘Helmsman, hard a starboard.’

Price swept the whipstaff to port, the tiller moving in reverse beneath him, coming hard up against the starboard. The bow swung slightly to port but with only the foremast storm tops’l to carry the weight of the entire galley, the Retribution could not make headway. She pitched violently as the waves crashed into her broadside.

‘Mister Seeley,’ Robert shouted over the roar of the wind, ‘take men forward and secure the braces to the yards of the foremast. If they fail we’re lost.’ Seeley nodded and Robert turned his attention to the men ascending the mainmast.

The pitch of the deck was making the climb difficult and more than once the men almost lost their footing on the shrouds as the ship heeled over. They reached the height of the main tops’l yard fifty feet above the main deck and Robert watched as Shaw directed Ellis and Foster to secure a new line for the brace. They worked swiftly, sidestepping out the footrope to the edge of the yard and within minutes Ellis descended with the new line.

‘Yeoman of the sheets, make fast!’

The petty officer called the men aft at Robert’s command and they secured and hauled in the line, their backs bent against the strength of the wind as they pulled the yard around into position.

Robert looked up at Shaw through the squalling rain and signalled him to come down, their task complete. The boatswain waved before he and Foster sidestepped back across the footrope to reach the head of the shrouds. On deck the crew continued to haul the yard into position. Suddenly the wind filled the main storm tops’l once more. The canvas took shape with a crack and the Retribution surged forward as if released from a sea anchor. Her bow swung swiftly around to its original position and the helmsman reacting without command to bring the rudder in line.

The rapid change, magnified by height, swung the head of the mainmast through an enormous arc and Foster lost his grip on the ratlines. His scream for help was cut short as Shaw grabbed one of his hands and the sailor swung out over the gaping drop to the main deck, his only lifeline the iron grip of the boatswain.

Robert heard the cries of alarm and looked up. His brief elation for the recovery of the Retribution’s course was immediately forgotten. Shaw clung to the ratlines at the edge of the shrouds with his right hand while Foster hung by his left hand beneath him. The sailor flailing his legs in panic and his free hand clawed at Shaw’s wrist as if trying to drag him down. Robert reacted without thought, racing down to the main deck and the base of the shrouds, shouldering past the crewmen who stared in horror at the men above, many of them shouting hopeless counsel. He jumped up onto the bulwark and climbed up the shrouds, his eyes darting between his feet and hands to the men hanging above him.

The wind tore at his body, the rain lashed his face and Robert blinked rapidly to try to clear his vision. Foster’s screams came to his ears, desperate cries that even the howling gale could not hide. He could also hear Shaw’s entreaties, trying to quell Foster’s panic, yelling at him to grab the underside of the shrouds with his free hand. But Foster was oblivious to all help, his fear-ridden instincts controlling him and he clung to Shaw’s left hand.

‘Shaw!’ Robert called as he approached. The boatswain looked to him for the first time. His face was mottled red with exertion, his eyes wild, and Robert could see the muscles of his arm tremble with the effort of holding himself to the ratlines and Foster from his death.

The Retribution bucked through the crest of a larger wave, its bow coming up short for a heartbeat before driving through into the trough, the rhythm of the galleon’s roll spoiled by a larger wave. All three men were caught unawares and their weight was thrown forward. Robert tightened his grip and held his footing but in that instant Shaw’s feet slipped and he swung around the edge of the shrouds. His right hand held firmly on the ratline but Foster was wrenched from his left and the sailor screamed as he fell through the rain to slam into the main deck forty feet below.

Robert scrabbled the last few feet to Shaw, his eyes locked on the boatswain’s precarious grip on the ratlines. Shaw swung out over the deck, his own gaze fixed on the shattered body of Foster below, while the constant waves mercifully washed the deck of blood.

‘Hold fast,’ Robert shouted and again the boatswain looked to him, this time his eyes betraying his fear.

‘I can’t …’ he shouted and Robert reached out desperately as he saw the boatswain’s grasp fail.

He grabbed Shaw’s hand just as his grip gave way. The weight of the boatswain slammed Robert into the shrouds. A searing pain ripped through his shoulder. Shaw dangled beneath him, re-enacting the last moments of Foster’s life. The boatswain reached up with his other hand and grabbed Robert’s wrist. His nails tore his flesh, trying to find purchase. Robert held firm, keeping his own body weight centred as the roll of the ship increased the swing of the boatswain’s body.

‘The ratlines,’ Robert hissed through clenched teeth. ‘Your other hand, man. Grab the ratlines.’

The boatswain’s face was a mask of terror. Robert felt the first weakness of his own grip on the ratlines as the boatswain swung through another pendulum’s arc.

‘Shaw!’ he screamed, the anger in his voice reaching the boatswain. ‘Grab the ratlines or you’re a dead man.’

Shaw nodded and Robert saw the fear in the boatswain’s eyes turn to determination.

‘Wait for the pitch,’ he shouted. As the Retribution crested a wave, the boatswain released his left hand and reached out for the underside of the shrouds. He missed but on the return swing his fingertips caught their outer edge. His hand clasped the rope, clinging to it.

‘Pull!’ Robert shouted. He used the last of his strength to heave the boatswain up, their hands releasing each other without command as each took their own grip on ropes. The boatswain was now swinging two handed beneath the shrouds and Robert reached out to grab his tunic, pulling him in to allow him to get his feet onto the ratlines. He climbed around to the outside and the two men clung to the ropes side by side, their laboured breaths whipped away by the wind and rain, while the all pervasive roar of the storm smothered the sounds of the cheering crew on the deck below.

Father Blackthorne moved slowly towards the halo of soft light surrounding the single candle framed in the window. He paused, wary as always of a trap, his caution almost second nature after years in hiding. The night was quiet save for the sounds of nature; the scurry of a small animal in the undergrowth, the screech of an owl, but still the priest hesitated, his breathing shallow as he strained for the sounds of some larger predator. His hand slipped inside his cassock and enfolded the crucifix hanging there. He silently mouthed a Latin prayer before stepping forward once more.

He crossed the courtyard and stopped at the door to the kitchen, knocking lightly as he glanced over his shoulder, conscious that he was now standing in the pool of light from the candle-lit window. The door opened a fraction and a man’s face appeared, furtive eyes betraying a moment of apprehension before he recognized the priest, smiling as he opened the door wider to allow him to enter. The priest ducked in and the door was closed and locked, the mechanism of the bolt unnaturally loud in the confines of the room.

The draught from the closing door had set the flame of the candle dancing and the kitchen came alive with moving shadows before the light settled once more, its soft glow allowing Father Blackthorne to feel more at ease. He turned to the man beside him and placed his hand on the servant’s expectantly bowed head.

‘In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti,’ he intoned.

‘Amen,’ the man replied. He looked up. ‘You must be hungry, Father,’ he said, ushering the priest to the table in the middle of the room.

Father Blackthorne sat down, his eyes poring ravenously over the table before him. The servant brought the lighted candle from the window sill to the table and the priest moaned involuntarily as he saw the feast in detail. He had not seen food like it in weeks and he reached out to pull the leg off a cold capon as the servant poured him a goblet of wine. He ate quickly, conscious that time was short, ignoring the servant who sat silently across from him.

‘I beg your forgiveness, Father,’ the servant said tentatively after five minutes, ‘but the Duke will be waiting.’

Father Blackthorne made to dismiss the reminder but held his tongue, knowing it would serve no purpose and that the duke’s good favour was all important. He stood up and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, belching softly with regret as he looked over the table of food once more. Its abundance was in stark contrast to the meagre offerings the poorer Catholics would give him in the weeks between now and his next visit to the duke’s residence.

The servant picked up the candle and led the priest from the kitchen, taking him along one of the servants’ passageways that emerged into the entrance hall of the estate house. All was in darkness. The two men crossed the flagstone floor in an orb of light and the feeble glow from the candle seemed to augment the vastness of the vaulted ceiling above them. Their footfalls echoed in the silence. They came to a door and the servant knocked. His hand was already on the handle as the command to enter was given.

Father Blackthorne entered alone. He felt anxious, as was often the case in the presence of his patron. The room was a small study, its walls lined with shelves holding innumerable books and the priest looked at them admiringly, conscious of their value. The Duke of Clarsdale was standing in front of the remains of a small fire in the hearth. He was surrounded in a thin haze of smoke from the downdraught in the chimney and his back was arched slightly as he outstretched his hands towards the heat. He was a tall man, broad across the shoulders and his iron grey hair gave twenty years to his middle age. He did not move as the priest crossed the room towards him, and Father Blackthorne’s eyes were drawn to the two Irish wolfhounds curled up at the edge of the hearth. Their heads turned to track the priest across the room before falling once more onto their extended legs.

‘I expected you quite some time ago,’ Clarsdale said.

‘It is becoming more and more difficult for me to travel,’ the priest explained.

Clarsdale murmured a reply and the room became silent once more.

‘It is becoming more difficult for us all,’ he said after a pause.

‘It is through our hardships that we are redeemed,’ Father Blackthorne replied, stepping closer to the duke.

Clarsdale did not reply immediately.

‘I was thinking of the men who were martyred last September,’ he said to the fire, a hard edge to his voice.