По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

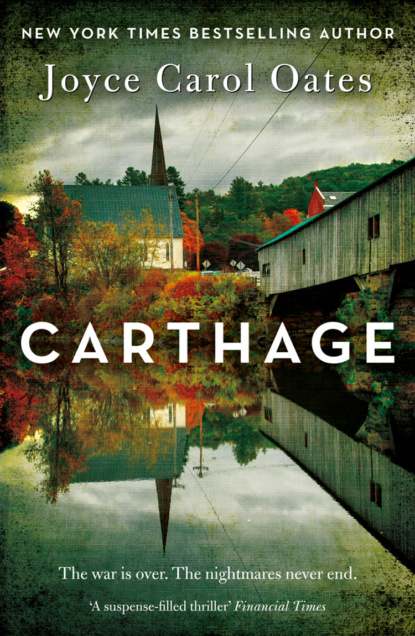

Carthage

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I wish that I could speak with your mother but I—I have tried . . . I have tried and failed. Your mother does not like me.

My mother says We’ll keep trying! Mrs. Kincaid is fearful of losing her son.

I know that you don’t like me to talk about your mother—I am sorry, I will try not to. Only just sometimes, I feel so hurt.

I know, the war is a terrible thing for you to remember. When you start classes at Plattsburgh in September, or maybe—maybe it will be January—you will have other things to think about . . . By then, we will be married and things will be easier, in just one place.

I will take courses at Plattsburgh, too. I think I will. Part-time graduate school, in the M.A. in education program.

With a master’s degree I could teach high school English. I would be qualified for “administration”—Daddy thinks I should be a principal, one day.

Daddy has such plans for us! Both of us.

I WISH YOU would speak of it to me, dear Brett.

I’ve seen documentaries on TV. I think I know what it was like—in a way.

I know it was a “high” for you—I’ve heard you say to your friends. Search missions in the Iraqi homes when you didn’t know what would happen to you, or what you would do.

What you’d never say to me or to your mother you would say to Rod Halifax and “Stump”—or maybe you would say it to a stranger you met in a bar.

Another vet, you would speak with. Someone who didn’t know Corporal Brett Kincaid as he’d used to be.

There is no “high” like that in Carthage. Tossing your life like dice.

Our lives since high school—it’s like looking through the wrong end of a telescope, I guess—so small.

Those sad little cardboard houses beneath a Christmas tree, houses and a church and fake snow like frosting. Small.

EVEN OUR WOUNDS here are small.

IN CARTHAGE, your life is waiting for you. It is not a thrilling life like the other. It is not a life to serve Democracy like the other. You said such a strange thing when you saw us waiting for you by the baggage claim, we were thrilled you were walking unassisted and this look came in your face I had not ever seen before and it was like you were afraid of us for just a moment you said Oh Christ are you all still alive? I was thinking you were all dead. I’d been to the other place, and I saw you all there.

THREE (#ulink_0f00dfe3-ceb3-5710-89e7-99cfb39c1604)

The Father (#ulink_0f00dfe3-ceb3-5710-89e7-99cfb39c1604)

OH DADDY WHY’D YOU call me such a name—Cressida.

Because it’s an unusual name, honey. And it’s a beautiful name.

FIRE SHONE INTO the father’s face. His eyes were sockets of fire.

He hadn’t the strength to open his eyes. Or the courage.

The doe’s torso had been torn open, its bloody interior crawling with flies, maggots. Yet the eyes were still beautiful—“doe’s eyes.”

He’d seen his daughter there, on the ground. He was certain.

The sick-sliding sensation in his gut wasn’t unfamiliar. In that place, again. The place of dread, horror. Guilt. His fault.

And how: how was it his fault?

Lying on his back and his arms flung wide across the bed—(he remembered now: they’d brought him home, to his deep mortification and shame)—that sagged beneath his weight. (Last time he’d weighed himself he’d been, dear Christ, 212 pounds. Heavy and graceless as wet cement.)

A memory came to him of a long-ago trampoline in a neighbor’s backyard when he’d been a child. Throwing himself down onto the coarse taut canvas that he might be sprung into the air—clumsily, thrillingly—flying up, losing his balance and falling back, flat on his back and arms sprung, the breath knocked out of him.

On the trampoline, Zeno had been the most reckless of kids. Other boys had to marvel at him.

Years later when his own kids were young it had become common knowledge that trampolines are dangerous for children. You can break your neck, or your back—you can fall into the springs and slice yourself. But if he’d known, as a kid, Zeno wouldn’t have cared—it was a risk worth taking.

Nothing in his childhood had been so magical as springing up from the trampoline—up, up—arms outflung like the wings of a bird.

Now, he’d come to earth. Hard.

HE’D TOLD THEM like hell he was going to any hospital.

Fucking hell he was not going to any ER.

Not while his daughter was missing. Not until he’d brought her back safely home.

He’d allowed them to help him. Weak-kneed and dazed by exhaustion he hadn’t any choice. Falling on his knees on sharp rocks—a God-damned stupid thing to have done. He’d been pushing himself in the search, as his wife had begged him not to do, as others, seeing his flushed face and hearing his labored breath, had urged him not to do; for by Sunday afternoon there must have been at least fifty rescue workers and volunteers spread out in the Preserve, fanning in concentric circles from the Nautauga River at Sandhill Point where it was believed the missing girl had been last seen.

It was the father’s pride, he couldn’t bear to think that his daughter might be found by someone else. Cressida’s first glimpse of a rescuer’s face should be his face.

Her first words—Daddy! Thank God.

HE’D HAD SOME “heart pains”—(guessed that was what they were: quick darting pains like electric shocks in his chest and a clammy sensation on his skin)—a few times, nothing serious, he was sure. He hadn’t wanted to worry his wife.

A woman’s love can be a burden. She is desperate to keep you alive, she values your life more than you can possibly.

What he most dreaded: not being able to protect them.

His wife, his daughters.

Strange how when he’d been younger, he hadn’t worried much. He’d taken it for granted that he would live—well, forever! A long time, anyway.

Even when he’d received death threats over the issue of Roger Cassidy—defending the “atheist” high school biology teacher when the school board had fired him.

He’d laughed at the threats. He’d told Arlette it was just to scare him and he certainly wasn’t going to be scared.

Just last month his doctor Rick Llewellyn had examined him pretty thoroughly in his office. And an EKG. No “imminent” problem with his heart but Zeno’s blood pressure was still high even with medication: 150 over 90.

Blood pressure, cholesterol. Fact is, Zeno should lose twenty pounds at least.

On the bed he’d tried to untie and kick off the heavy hiking boots but there came Arlette to pull them off for him.

“Lie still. Try to rest. If you can’t sleep for Christ’s sake, Zeno—shut your eyes at least.”