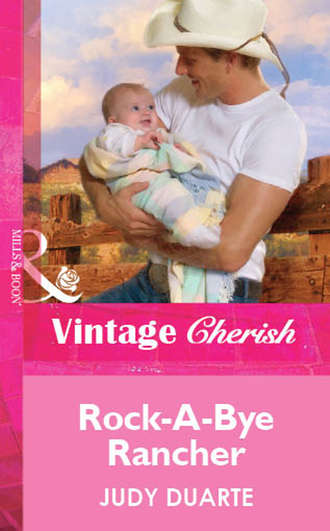

Rock-A-Bye Rancher

The first thing she did when she walked through the front door was snatch the newspaper and scan the movie listings, choosing one that the younger children and Mrs. Fuentes would appreciate. Then, with Delia hot on her heels, she rushed to her bedroom to pack.

She didn’t have a clue as to what the weather was like in Guadalajara, so she took twice as many clothes as she’d need. As she carefully placed her things in the old suitcase that had been her father’s, she realized it was pretty battered and not in the style of a career-minded professional. But that was too bad. She was doing the best she could, under the circumstances.

“How come you have to go away for the whole night?” Delia asked, as she peered into Dani’s room. “Who’s going to read me the next chapter of Charlotte’s Web when I go to bed?”

“I’m sure Mrs. Fuentes will read it to you,” Dani said.

Marcos, who stood in the doorway, asked, “Will you take me to see Revenge of the Zombies when you get home?”

Dani wanted to say no, but she felt terrible about leaving like this. Guilt was an amazing thing, wasn’t it? Especially when she suspected Marcos was using it to his advantage. But there wasn’t much she could do about that now.

“What’s the zombie movie rated?” she asked, as she took a quick inventory of her cosmetic bag, then packed it in the suitcase.

“It’s PG-13, but not because anyone gets naked or because they say bad words. It’s not even violent, because the Zombies have green blood and even a little kid knows that’s fake.”

Dani wasn’t in the mood to debate the fact that the Motion Picture Association had rated it PG-13 for some reason. Or that a movie can be violent in spite of the color of a victim’s blood and guts. “Okay, you and I can give it a try on Saturday. But if I decide it’s inappropriate for a boy your age, we’ll have to leave in the middle of it.”

“You won’t think that. I know ’cause my friends have all seen it. There aren’t even guns and knives, just lasers and that sort of thing.”

Yeah. Right.

Dani glanced at the clock on the bureau. Shoot. An hour and twenty minutes had already passed, and it would take fifteen minutes to get back to the office—unless she hit traffic.

The fact that Mr. Callaghan was waiting for her made her move faster, causing her hands to shake as she snapped the suitcase lid into place.

Then she kissed the kids goodbye, promising them treats if Mrs. Fuentes gave her a good report.

An hour and forty-two minutes after leaving the building, Dani returned with her suitcase in hand. She could feel the moisture building under her arms and along her scalp. But she mustered a smile and tried her best to act as though the errands she’d run had been similar to those of any single, twenty-five-year-old woman.

As she entered the reception area, Mr. Callaghan, who’d been waiting near the door, stood. The walls of the room seemed to close in on them, and she got a lungful of his musky, leathery scent.

“Ready?” The question slid over her like the whisper of a breeze on a sultry Houston night. Her heart, which was already pumping at a pretty good pace, began to beat erratically, which didn’t make a bit of sense. She’d never been attracted to the cowboy type before. Or to a man who was nearly old enough to be her father.

Clay Callaghan was so not her type.

If she were in the market for romance—and God knows she wasn’t—she would look for a successful young professional. Another attorney, maybe. Someone well-read, witty. Polished. Not a self-made man who couldn’t kick his cowboy roots and might be twenty years her senior.

But tell that to the suddenly active hormones she’d kept under lock and key for the past couple of years.

She smiled, hoping it hid the fact that she might appear to be ready, but she wasn’t eager to travel on a small plane with an important client, a man she didn’t know very well, a rugged outdoorsman she was oddly attracted to.

“Yes,” she lied. “Let’s go.”

As Clay took the suitcase from the pretty Latina’s hand, his fingers brushed against hers. Their eyes locked, and something sparked between them. Something he had no business contemplating, especially since it seemed to fluster the hell out of her.

Damn, she was young. And pretty. She wore her glistening black hair swept up in a professional twist, although a few strands had escaped. It had been neatly coiffed before, but not so anymore. He suspected her rush to get packed, run a few errands and race back to the office had rumpled her.

That was okay with him. He wasn’t attracted to women who wore business suits or who had to powder their noses and reapply lipstick all day long.

Not that he was on the prowl these days. Or that he had time to do anything more right now than fly to Guadalajara, pick up the baby and head home. They’d be gone one night and a day, best he could figure.

Of course, that was assuming the child was Trevor’s. But until he got her home and ran a DNA test, he wouldn’t know for sure.

And if she wasn’t his flesh and blood?

Then he’d talk to his foreman, “Hawk” Hawkins, whose brother and sister-in-law had been trying to conceive for years and were talking adoption.

Either way, he’d face that road when he came to it. Clay might have made a lot of mistakes with his son over the years, but he wouldn’t fail his granddaughter.

He opened the office door for Daniela, then followed her out into the hall.

She fingered the side of her hair, just now realizing she was falling apart, and a grin tugged at his lips. For an attorney who was supposed to be bright and capable, she seemed a little ill-at-ease to him.

She’d just passed the bar, he’d been told. And had a slew of recommendations from her professors at law school, not to mention she was second in her class.

That was impressive, he supposed, assuming someone was big on academics, which he wasn’t. The most valuable lessons were learned in the real world. That’s why going to college had never crossed Clay’s mind. Instead he’d prided himself on his ranching skills, his common sense and an innate head for business. He’d done all right for himself. Hell, he had more money than he knew what to do with.

At the elevator, Daniela punched the down button, then glanced up at him and smiled. She had to be closer to twenty than thirty, if you asked him. Of course, it might just be her size. She only stood a little over five feet tall and was just a slip of a thing.

The elevator buzzed, and when the door opened, they stepped inside.

“So tell me about your granddaughter,” she asked.

“There’s not much to tell. I’ve never seen her before.”

“How old is she?”

He shrugged. “I forgot to ask.”

She cocked her head, perplexed, he supposed. But he didn’t see what the kid’s age had to do with anything, other than prove that it was possible Trevor had fathered her.

“The baby has to be less than a year old,” he said, “but more than two months.”

As they continued their descent to the ground floor, the scent of her perfume swirled in the elevator. It was something soft and powdery. Peaches and cream, he guessed.

“Are you sure the child is your son’s?” she asked.

“Nope.” But the fact that it might be was reason enough to go to Mexico and bring her home.

“There are blood tests that can prove paternity,” she said.

He nodded. “Yeah. I know that.” He’d have the test run after he got back in the States. “But let’s take this one step at a time.”

“And that first step would be…?”

“Getting that baby home.”

When they reached the ground floor, the elevator opened and they entered the spacious lobby.

Clay stepped ahead, then opened the smoky-glass double doors and escorted her outside and down the walkway to the parking lot. “My truck is in the second row. To the left.”

When they reached the stall where he’d parked his black, dual-wheeled Chevy pickup, he pulled the keys out of his pocket and clicked the lock. He tossed her suitcase in the bed of the truck and opened the passenger door. Then he removed his duffle bag and waited for her to climb inside.

She bit down on her bottom lip, as she perused the oversize tires that made the cab sit higher than usual. He couldn’t help but grin. She was going to have a hell of a time climbing into the seat with that tight skirt. An ornery part of him thought he’d stick around and watch the struggle. She placed a hand on the door, then lifted her foot and placed it on the running board.

Pretty legs.

“Need some help?” he asked.

“No, I can manage.”

Rather than gawk, which he had half a notion to do, he tossed his bag in the back of the truck. As she continued to pull herself into the Chevy, the fabric of her skirt pulled tight against her rounded hips. She might be petite, but she was womanly. And damn near perfectly shaped.

She slid into the seat, then glanced around the cab. “Where are the baby’s things?”

The baby’s things? Hell, he hadn’t given that any thought. All he’d wanted to do was talk to his attorney, fly to Mexico, get the kid and head home.

She crossed her arms, causing her breasts to strain against the fabric of her blouse. “Don’t tell me you don’t have anything packed for an infant?”

Okay, he wouldn’t tell her that. But he didn’t have squat for the kid. In fact, he wasn’t prepared to take on a baby at all, and in his rush to get to Mexico, he hadn’t given supplies any thought. Nor had he given much thought to what he’d do with the kid, once he got her home.

“I don’t know much about babies or their needs. Hell, I never even held my son until he was close to two.”

“Well then, like you said, we’ll need to take this one step at a time. I suggest you stop by Spend-Mart. It’s just down the street and ought to have everything you need.”

“I hope you have a few suggestions. I don’t have a clue what to get.”

“Believe it or not, I have a pretty good idea. But it won’t be cheap.”

Neither was the trip to Mexico. But money was the last thing Clay had considered. Not when he was still carrying a ton of grief over Trevor’s death.

The pastor who’d spoken at the memorial had told Clay it would take time. But so far the weight on his chest hadn’t eased up a bit.

Minutes later Clay and Daniela entered the crowded department store.

“Get a shopping cart,” she told him, taking the lead. For some fool reason, Clay, who never was one to follow orders, complied.

In no time at all, she had the cart filled with disposable diapers, wipes, ointments, lotions, pacifiers. Next, she threw in bottles, formula—both readymade in the can and powdered in packets—plus a couple of jugs of water. Then she zeroed in on receiving blankets, pajamas, undershirts and clothes.

“You already have one of those,” he said, nodding to the pink and white PJs. “But in purple.”

“We don’t know what size she wears, so we’ll keep the receipt and return whatever doesn’t fit.”

Clay merely nodded his head as he followed the pretty, dark-haired attorney through the baby section.

For a single woman, she sure was adept at knowing what things he was going to need. What an intriguing contradiction she was. On the outside, she seemed every bit as professional and competent as Martin Phillips had insisted she was. But there was obviously a maternal and domestic side to her, as well.

“This ought to get us started,” she said. “You can go shopping again, after you get her home.”

“Maybe you can do that for me,” he said.

She arched a brow. “My fees are $250 an hour. I’m sure you can find someone better qualified and cheaper.”

“But maybe not someone who knows as much about kids as you do.”

He meant it as a joke, as a way of telling her he didn’t give a damn about the cost. But she stiffened for a moment, then seemed to shrug it off.

“I did a lot of babysitting in the past,” she explained.

“Lucky me.”

As they headed for the checkout lines, he couldn’t help but watch her. She seemed to be counting each item she’d chosen, taking inventory. Making sure they had all they needed.

So she’d spent her early years babysitting. Maybe her beginnings had been as humble as his.

She was interesting. Intriguing.

And attractive.

Not that he’d ever chase after a woman who would have been more his son’s type. And one who was definitely more his son’s age.

Chapter Two

Thirty minutes later Clay and Daniela arrived at Hobby Airport in Houston, where Roger Tolliver, Clay’s pilot, had already filed a flight plan and was waiting to take off. Roger, a retired air force captain with thousands of hours of experience, was doing his final check of the twin-engine King Air, which Clay had purchased from the factory last year.

After parking his truck and unloading their luggage and purchases, Clay removed the baby’s car seat from the box so it would fit in the plane better. Then he juggled it and the heavier items, along with a briefcase, a black canvas gym bag that carried a change of clothing and his shaving gear.

“It’s this way,” Clay told Daniela, who carried her purse, a small brown suitcase and several blue plastic shopping bags, as he headed toward the plane.

The competent young attorney, who’d been leading the way through Spend-Mart and racking up a significant charge on Clay’s American Express, was now taking up the rear. Clay had a feeling it wasn’t the load she was carrying that caused her to lag behind.

He glanced over his shoulder and, shouting over the noise of a red-and-white Cessna that had just landed, asked, “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.” She carefully eyed his plane, as well as the salt-and-pepper-haired pilot.

“Don’t tell me you’re skittish about flying,” he said.

“All right. I won’t.”

Great. His traveling companion was a nervous wreck. Maybe, if she felt more confident about the man in charge of the plane, she’d relax.

When they reached the King Air, Clay greeted the pilot. “Roger Tolliver, this is my attorney, Daniela de la Cruz.”

“Pleased to meet you, ma’am.” The older man took the bags from her hands.

“As you can see,” Clay told Roger, “we’ve got quite a few things to take along. Daniela reminded me that we’d need supplies for the baby, so we bought out the infant department at Spend-Mart.”

“I had a couple kids of my own, so I know how much paraphernalia is needed.” Roger nodded toward the steps that would make it easy to board the plane. “Why don’t you make yourselves comfortable. I’ll pack this stuff.”

Before long, the hatch was secured, and they were belted in their seats. As they taxied to the runway, Clay couldn’t help but glance at the woman beside him, her face pale and her eyes closed. White-knuckled fingers clutched the armrests of her seat. She sat as still and graceful as a swan ice sculpture on a fancy buffet table. The only sign of movement was near her collarbone, where the beat of her heart pulsed at her throat.

Damn. She really was nervous.

“Daniela,” Clay said over the drone of the engine, thinking he’d make light of it, tease her a bit to get her mind on something else. But when she opened her eyes, her gaze pierced his chest, striking something soft and vulnerable inside. Without warning, the joke slipped away, and compassion—rare that it was—took its place. “Hey. Don’t worry. Roger was flying before you were even born. He’s got a slew of commendations from the air force. He’ll get us to Mexico and back before dinnertime tomorrow.”

“That’s nice to know.” She offered him a shy smile, then slid back into her frozen, sculptured pose.

According to Martin, the senior partner in the firm and Daniela’s boss, she was a bright, capable attorney. But she was clearly not a happy flyer.

Damn. This was going to be a hell of a long trip if she didn’t kick back a little and relax.

Moments later the plane took off, heading for Guadalajara. Once they were airborne, Clay offered her a drink. “It ought to take the edge off your nervousness.”

“I’m not big on alcohol,” she said.

“How about a screwdriver?” he pressed. “Orange juice with just enough vodka to relax you?”

She pondered the idea momentarily. “All right. Maybe I should.”

He got up and made his way to the rear of the plane—just a couple of steps, actually—and fixed her a drink from an ice chest Roger had prepared. He poured himself a scotch and water, too, then returned to his seat. “It’s a pretty day. Take a look out the window.”

She managed a quick peek, but didn’t appear to be impressed.

“How long have you been working for Phillips, Crowley and Norman?” he asked.

“A little over a year.”

He wondered what age that would make her. Pushing into the late twenties, probably. Hell, she wasn’t much older than Trevor would have been. And he suspected she was probably the same studious, bookworm type as his son. College-educated folks usually were.

Clay and his son hadn’t had a damn thing in common—other than a love of flying the King Air and the Bonanza they’d owned before that. And though there’d been a bond of sorts, the two of them had butted heads more times than not.

Maybe if Clay’s old man had stuck around long enough to be a father to him, it might have helped Clay know how to deal with his own son. But Glen Callaghan had been a drifter. Clay’s only other role model had been Rex Billings, a gruff and crusty cattleman who used to hang out at The Hoedown, a seedy bar on the outskirts of Houston where Clay’s mom worked as a waitress. When his mom was diagnosed with terminal cancer, the old cowboy took her and Clay in, letting them live at his place.

Never having a family of his own, Rex hadn’t quite known what to do with a ten-year-old boy, but he’d given it his best shot, teaching Clay how to be tough, how to be a man. There was never any doubt that Rex had come to love Clay, even though the words had never been said. And when Rex died, he left the Rocking B Ranch and everything he owned to the young man who’d become a son to him.

Clay had done his best to turn the cattle ranch into a multimillion dollar venture. And over the past twenty years, that’s exactly what he’d done. He’d become a hell of a businessman. But in the long run, he’d been a crappy dad.

He’d tried his damnedest to teach Trevor the things a boy ought to know, the things Rex had taught Clay: to be tough; to work hard; to suck it up without grumbling.

Trevor used to complain that Clay never had time for him. But hell, if the kid had gotten his nose out of those books he carried around and quit carping about his allergy to alfalfa, they might have gotten along as well as Rex and Clay had.

But that didn’t mean Clay hadn’t tried to reach out to the kid in his own way. He’d suggested a fishing trip when Trevor turned sixteen, but that idea had gone over like a sack of rotten potatoes. He’d also asked Trevor to accompany him to an auction, thinking they could hang out a few days afterward. But for some reason, you’d think Clay had suggested they go to the dentist for a root canal.

Clay wasn’t sure what the boy had expected from him. But instead of having the kind of relationship either of them might have liked, they merely passed each other in the hall.

Of course, he’d meant to remedy that when Trevor got a little older—and a little wiser—hoping that after his son graduated from college, they’d find some common ground. He’d kept telling himself that things would be better between them—one of these days.

But one of these days came and went.

Clay tried to tell himself he hadn’t failed completely. He’d tried to make up for things in other ways, like buying Trevor a state-of-the-art computer system, paying for out-of-state tuition and allowing him to go on that international study abroad program that landed him in Guadalajara, where he died.

And there it went again. Full circle.

Thoughts of Trevor led to thoughts of his shortcomings as a father and the load of guilt he carried for not doing something about it—whatever that might have been—when he’d had the chance. He did the best he could to shove the feelings aside, as Rex had taught him, forcing them to the dark pit in his chest.

What was done was done.

Clay may have failed Trevor, but he wasn’t going to let his granddaughter down—assuming the baby was a Callaghan. So he looked out the window, focused his gaze straight ahead. Shoved those feelings down deep, where they belonged.

Thirty minutes or more into the flight, Daniela had managed to finish her vodka-laced juice and had seemed to relax a bit—until they hit an air pocket. Then she paled.

“Sorry about that.” Roger glanced over his shoulder and caught Clay’s eye. “Better fasten your seat belts, folks. It’s going to be bumpy for a while.”

The pilot nodded toward the windshield at the dark gray sky ahead. Roger planned to fly around the storm. And he’d warned Clay earlier that it would be a bumpy flight, although there was no reason to suggest they would be taking any unnecessary chances. Clay was, however, determined to get the baby out of Mexico and back to the States as quickly as he could, so he would have agreed to any risk Roger was willing to make. Still, he hated seeing Daniela so uneasy.

Under normal circumstances, with any other attorney, he would have been annoyed. But there was something about Daniela that made her different. And it wasn’t just her gender and her youthful beauty.

Okay, maybe it was.

Clay had never been one to chase after younger women. He preferred someone with maturity, someone who wasn’t interested in settling down.

Hell, he’d never even married his son’s mother. He and Sally had met at the feed lot and had a brief but heated affair. There hadn’t been much emotion involved. Of course, there never was on Clay’s part, and he always managed to find a lover with the same no-strings philosophy. Sally hadn’t seen any reason to get married, either, which was a relief.

As the plane hit another rough spot, he stole a glance at his traveling companion. Distress clouded her expression, the contradiction of competent attorney and frightened passenger intriguing him. Hell, he couldn’t sit idly by and watch her come apart at the seams—no matter how much he enjoyed looking at her.

“It shouldn’t be much longer,” Roger said.

The plane bounced again, causing Daniela to nearly drop her drink.

“Finish it,” Clay told her, and she quickly obliged. He wondered if she assumed his order had been due to safety reasons, but it didn’t matter. He was just hoping she’d consume enough alcohol to feel more at ease. So far, it didn’t seem to be working.

The next time the plane dipped, she reached across the aisle and grabbed his hand, gripping him tightly.

Her touch, as well as her vulnerability, struck an unfamiliar chord in him, and he found himself stroking the top of her wrist with his thumb, comforting her much the way he would a skittish filly.

“That should be the worst of it,” Roger announced.

Yet Daniela didn’t let go.

Her hand was small, her nails unpolished and filed neatly, her skin soft. Yet her grip was strong.

Clay had half a notion to draw her close, to offer her more than a hand to hold.

Now where the hell had that wild-ass thought come from?

Clay had never been one to mess with the touchy-feely stuff. And the fact that he’d let down his guard and nearly done so, didn’t sit well with him. So he did the only thing he could think of. He offered her another drink.

Interestingly enough, she agreed without much hesitation.

“A little turbulence is no big deal,” Clay told her. “Really. Think of this as a car going along a bumpy road.”

Yeah, right, Dani thought.

When it came to aerodynamics, that was probably true. But it felt as though there were only clouds holding them up, and the waters of the gulf below were waiting to swallow them whole. That is, unless they’d already crossed over the Mexican border, in which case…