По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

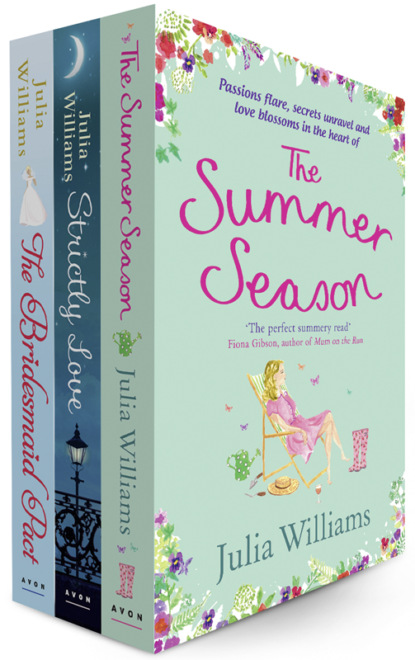

Julia Williams 3 Book Bundle

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Some of it is,’ said Kezzie, ‘but writing rude things about people you don’t like isn’t. And it seems disrespectful too. My granddad was in the war, so I always wear a poppy for him.’

‘I agree with you on that one,’ said Joel. ‘Do you know, I hadn’t even realized there was a war memorial till you mentioned it. I don’t come here that often.’

‘Not even to take Sam to the swings?’ said Kezzie.

Joel shrugged. ‘Have you seen them?’

Kezzie followed him down the furthest path, that led from behind the plinth towards some overgrown bushes. Behind the bushes there was a tatty play area, with an ancient rusty roundabout, two creaky swings and a slide that looked as though it might topple over if anyone actually tried to use it.

‘This is ridiculous,’ said Kezzie. ‘Don’t you guys want somewhere for the kids to come and play?’

‘I hadn’t really given it much thought,’ said Joel. ‘Until recently, Sam’s been a bit small to take to the playground, and I’ve got plenty of room at home. I think Lauren comes down here, though.’

‘I bet she’d like a clean, safe place for the twins to play,’ said Kezzie. ‘Right. That’s it. I’m going to get on to Eileen about this the minute I get back. It’s time we shook this village up.’

Good as her word, once Kezzie was home, had said goodbye to Joel and grabbed a bite to eat, she was straight round to Eileen’s.

‘You’re absolutely right,’ she said, sweeping in. ‘Oh, you’ve got company.’

‘Just my son and family, and you’ve met Tony,’ said Eileen, smiling. ‘You can come and join us if you like.’

Kezzie felt wrongfooted. Until last night, when she’d seen Eileen out with Tony, Kezzie had pictured Eileen as a sad singleton. Here she was having a much livelier time than Kezzie, who spent Sunday evenings on her own.

‘Oh I couldn’t—’

‘Of course you could,’ said Eileen. ‘Pull up a chair, grab a glass of wine. This is my new neighbour, Kezzie. Kezzie, meet my son Niall, his wife, Jan, and my two scamps of grandsons: Harry and Freddy.’

Before long, Kezzie found herself telling them all everything she’d discovered about Edward Handford.

‘That’s fascinating,’ said Eileen. ‘I’ve not been able to find out a lot about Edward’s family, though I do know his son died in the war.’

‘Maybe that’s why Edward paid for the memorial,’ said Kezzie.

‘Could be,’ said Eileen. ‘It’s still sitting locked up in some council warehouse somewhere.’

‘Shocking,’ whistled Niall. ‘Was that the old memorial we used to play on in the park?’

‘The very same. We always used to attend the Remembrance Sunday parade with your dad and granddad. Do you remember?’

‘Yes, I remember,’ said Niall, ‘I can’t believe they’ve not put it back.’

‘Neither can I,’ said Tony. ‘I hadn’t realized it was an issue till Eileen raised it at a Parish Council meeting.’

‘What happens on Remembrance Sunday now?’ Kezzie asked.

‘Everyone goes into Chiverton,’ said Eileen. ‘They’ve still got their memorial. It’s a shame, I’d love us to have our own Remembrance Day parade here again. Particularly with Jamie going to Afghanistan after Christmas.’

‘Jamie?’ Kezzie said. She knew Eileen had a daughter, Christine, but hadn’t realized there was another son.

‘My youngest son, he’s in the marines,’ said Eileen proudly, holding out a picture of a handsome young man in uniform. He looked impossibly young to be going to war.

‘That must be scary,’ said Kezzie.

‘I try not to think about it, if I can,’ said Eileen. ‘Otherwise I’ll go mad with the worry of it. But he’s one of the reasons I want to restore the war memorial, to remind people it still goes on.’

‘Time to get ours back then,’ said Niall.

‘The summer fete next year is all in aid of restoring the garden and play area,’ said Eileen. ‘And we’re trying to pressurize the council to give us our memorial back. They say they haven’t got the money to restore it, so we’re trying to shame them into it.’

‘Surely we don’t have to wait for them to start tidying up the garden though?’ said Kezzie. ‘We should get cracking and dig over the beds before the winter sets in and it’s too cold.’

‘Oh, if I know the Parish Council, they’ll be still debating that next spring, won’t they, Tony?’ said Eileen.

‘Sad, but true,’ said Tony with a grin.

‘Time we took matters into our own hands then, isn’t it?’ said Kezzie, grinning. ‘Just as well I’ve had practice breaking and entering.’

Chapter Eleven

‘So?’ said Troy, as Lauren came downstairs after she’d got dressed.

‘So what?’ said Lauren, as she put the kettle on, her embarrassment making her tetchy.

‘Have you thought any more about me seeing the girls?’

‘I’ve thought about nothing else since last night,’ said Lauren. ‘Look, you can meet them, but not yet. I need to sit down and talk to them about you. And we need to take it slowly. You can’t expect them to welcome you with open arms.’

‘Why? What have you said about me?’

‘Don’t flatter yourself,’ said Lauren. ‘I don’t talk about you that often. They know they’ve got a dad, but that you’re not around. Some of their friends are in the same situation and they know Sam hasn’t got a mummy, so they don’t ask a lot about you. But they’re likely to be shy, so don’t expect too much.’

‘So when can I see them?’

‘I’ll let you know,’ said Lauren, determined that if this was going to happen, it was going to be on her terms. ‘They’re going to be back soon, and I don’t want them to see you without any warning. So push off now, and I’ll give you a ring when you can come back.’

Troy got up slowly, as if reluctant to leave. He positively oozed charm and sexuality and Lauren had to fight very hard to counteract the strong feelings of desire that were stirring within her.

‘And us?’

‘What about us?’ said Lauren. ‘There is no us. You made that quite clear four years ago.’

‘So I can’t hope for anything?’ He moved closer towards her. She could smell his aftershave; a musky smell that reminded her of the tangled beds, and lusty afternoons, they’d spent together in the heady days in her second term at university when they’d first known each other. Don’t. Don’t think of that. She forced herself to concentrate on something else, but Troy wasn’t making it easy for her.

He brushed his lips across hers, and the touch of his hands on her shoulders was enough to make her want to give in and pull him straight towards her. But looking over his shoulder and seeing the picture Joel had taken of the twins on their first day at school, brought her to her senses. A sudden vision of herself in a hospital bed, unable to move after a caesarean with two screaming babies in cots beside her, swam before Lauren’s eyes. What was she thinking letting him worm his way in here again? She had to be stronger than that.

‘No,’ she said, pushing him away firmly. ‘You can’t. You had your chance and you blew it.’

‘We’ll see,’ said Troy, blowing her a kiss as she bundled him out of the door. ‘I can be very persuasive.’