По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

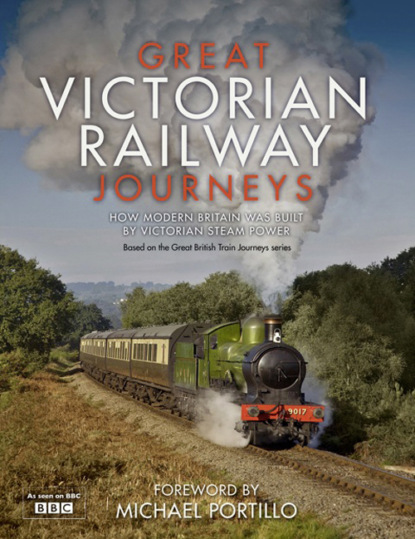

Great Victorian Railway Journeys: How Modern Britain was Built by Victorian Steam Power

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A steam train approaching Weybourne Station on the North Norfolk Railway.

Felixstowe finally got a town-centre railway station in 1898, courtesy of the Great Eastern Railway.

Midway between Ipswich and Colchester, Suffolk gives way to Essex, although the slow pace of rural life remained the same. When the Great Eastern main line crossed the River Stour on the Essex and Suffolk border it bisected an area known today as Constable Country. It contains, of course, the vistas that inspired artist John Constable. Some of his most famous works, including The Haywain and Flatford Mill, were painted here near his boyhood home of East Bergholt in Suffolk.

Constable died in 1837, the year Victoria came to the throne. During his lifetime his paintings were more popular in France than ever they were in England. Both he and fellow artist J. M. W. Turner were lambasted by critics of the day for being safe and unadventurous in their work. But Constable insisted he would rather be a poor man in England than a rich one overseas and stayed to forge a living in the only way he knew how.

His inspiration was nature, and his pictures often betrayed the first intrusions of the Industrial Age into rural life. Although he didn’t always live there, it was Suffolk scenes he was perpetually drawn to paint. ‘I should paint my own places best,’ he wrote. ‘Painting is but another word for feeling.’ An indisputably Romantic painter, his rich use of colour arguably laid the foundations for future trends in art.

The tallest Tudor gatehouse ever built lies further down the line, marking the half-way point between Colchester and Chelmsford. Aside from its architectural glory, Layer Marney Tower has two striking claims to fame. The first is that it was owned from 1835 by Quintin Dick, an MP made notorious by his practice of buying votes. Indeed, there’s some speculation that he spent more money bribing his constituents than any other MP of the era. The son of an Irish linen merchant, Dick spent a total of 43 years as an MP, representing five different constituencies.

© 19th era/Alamy

Layer Marney Tower, a Tudor palace damaged by the Great English Earthquake of 1884.

© Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Southend Pier, c. 1890.

The tower’s second claim to fame is that it and surrounding buildings built during the reign of King Henry VIII were badly damaged in the Great English Earthquake of 1884, which had its epicentre near Colchester. Afterwards a report in The Builder magazine stated the author’s belief that the attractive monument was beyond repair: ‘The outlay needed to restore the tower to anything like a sound and habitable condition would be so large that the chance of the work ever being done appears remote indeed.’

However, the tower was repaired, thanks to the efforts of the then owners, brother and sister Alfred and Kezia Peache, who re-floored and re-roofed the gatehouse, and created the garden to the south of the tower. Layer Marney Tower was one of an estimated 1,200 buildings damaged by the earthquake, which struck on 22 April and measured 4.6 on the Richter scale. There were conflicting reports about a possible death toll, ranging from none to five. The earthquake sent waves crashing on to the coastline where numerous small boats were destroyed.

From the main east coast line it eventually became possible to forge across country by branch line to Southend. It wasn’t the earliest line built to the resort, however, nor would it be the busiest. Contractors Brassey, Betts and Peto built the first railway into Southend from London, although plans to site the station at the town’s pier head were vetoed on grounds of nuisance. It was the last stop on a line that went via Tilbury and Forest Gate to either Bishopsgate or Fenchurch Street. Primarily managed by the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway Company, the line was known locally as the LTS.

After the railway was opened there was extensive development in the town, providing houses large and small at Clifftown. Samuel Morton Peto was once again a moving force in the plans. The homes were completed in 1870 and, a decade later, a newly designed tank engine went into operation on the LTS which could haul more people at faster speeds than ever before. For the first time people could live in Southend while working in London with ease, thanks to the train. Thus Southend became an early commuter town, as well as being the closest resort to London.

But its reputation was mainly thanks to the attractions of the seaside. In 1871 the law was changed to permit Bank Holidays – days when the banks were officially shut so no trading could take place. And, thanks to its closeness to London, the train brought in hordes of trippers to Southend for days out, particularly on the popular Bank Holiday that fell on the first Monday in August – initially known as St Lubbock’s day for the Liberal political and banker Sir John Lubbock who drove the necessary Act through Parliament.

An early wooden pier in the town, dating from 1830, was now beginning to show its age. Maintenance and repair bills were high. Its original purpose had been as a landing stage for boats bringing a few tourists from London. Now there were scores more tourists and the pleasure principle was about to take precedence.

Plans drawn up for a new iron pier included an electric railway to run its length. When it opened in 1890 there was a pavilion at the shore end that hosted concerts as well as the popular pier railway to entertain the crowds. According to the National Piers Society, £10,000 of the £80,000 costs was spent on the new electric railway. Notwithstanding, there was only a single engine on the three-quarter-mile-long track. Its 13-horsepower motor was powered by the pier’s own generator. Three years later a passing loop was installed and a second three-car train went into service.

Still it wasn’t sufficient capacity for the relentless number of trippers, particularly from East London, that made their way to Southend. Although a second generator was added in 1899 to help power two more trains, it wasn’t until the Southend Corporation built its own generating station in 1902 that the four trains could be extended to cater for more passengers. The pier generators were then scrapped.

The pier was continually extended, first to provide an access point for passing steamers, and secondly to accommodate holidaymakers. The final addition in 1929 brought the length to 2,360 yards (1.34 miles or 2,158 metres), making it the longest pleasure pier in the world.

Between Southend and London the landscape was largely lush and green in Victorian times, although the capital itself was becoming a spaghetti-mess of railway lines. Along with other railway builders, Great Eastern Railways was committed to developing suburban lines around London. One of them, terminating at Ongar, led to the Royal Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey. Initially a cloth mill, it is thought gunpowder was made there using saltpetre from the middle of the sixteenth century.

The site was taken under government control in 1787 to secure supply, and production stepped up from the middle of the nineteenth century to supply arms for the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and, later, the Boer War. It also became central to weapons science and technology. In 1865 a patent was granted for gun cotton, a new if somewhat unstable explosive, which was then produced at Waltham Abbey. It was also the focus of production for cordite, a smokeless alternative to gunpowder pioneered in 1889.

A network of railways crossed the site after a building programme escalated during the Crimean War at a time when steam could provide the necessary power for production. The rails were for wagons which were gently pushed rather than towed – a nod to the volatile cargo aboard. Initially the gauge of the rails was 2 ft 3 in.

© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans

Her Majesty's Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey.

In 1862 at Crewe, John Ramsbottom, chief engineer of the London & North Western Railway, proved the versatility of an 18-inch gauge for industrial trains, which could run not only up to but into warehouses. Eventually the gauge at Waltham Abbey was changed, so when production went into overdrive during the First World War the factory was at its most efficient.

Freight across the Great Eastern Railway was for years dominated by food. In addition to fish from the east coast there were vegetables – linking the fortunes of the railway company inextricably to the wealth of the harvest. There was also milk, which first travelled in churns hoisted into ventilated vans to keep it as fresh as it could be for thirsty city folk. This way the train service made a significant contribution to the health of the nation, supplying fresh food to cities at comparatively low costs.

In the same way (but in the opposite direction), railways carried newspapers fast and efficiently into rural areas, improving education and awareness everywhere in a way that was once confined to cities.

In 1847 the Eastern Counties Railway began to build a depot at Stratford where its locomotives were made. It was extended time and again throughout its history until it became a maze of track and workshops. In 1891, when it was under the aegis of the Great Eastern Railway, a new record was set there for building a locomotive. It took just nine hours and 47 minutes to produce a tender engine from scratch, complete with coat of grey primer. As a sign of the frantic railway times, the locomotive was dispatched immediately on coal runs, and covered 36,000 miles before returning to Stratford for its final coat of paint. Its working life lasted for 40 years and it ran through 1,127,000 miles before being scrapped.

When Bradshaw’s was written in 1866, the terminus of the Great Eastern line was Bishopsgate in Shoreditch. The guidebook calls it ‘one of the handsomest (externally) in London’. It was opened in 1840 by the Eastern Counties Railway and its name was changed from Shoreditch to Bishopsgate in 1847.

When Eastern Counties Railways amalgamated with other lines to form Great Eastern Railways, the new company found its two options for terminals – Bishopsgate and Fenchurch Street Stations – were not sufficiently large and set about building Liverpool Street Station and its approach tunnel, which opened in 1874.

© Mary Evans Picture Library

An engraving of Bishopsgate Street by Gustav Doré, 1872.

© Stephen Sykes/Alamy

Railway carriages at Weybourne Station on the North Norfolk Railway.

Nowhere in Britain has the railway map changed more than in London, not least due to the Blitz in the Second World War. In 1866 it was possible to jump on a North London line train at Fenchurch Street or Bow, within moments of getting off a Great Eastern line train.

This is a route that became infamous in 1864 for being the scene of Britain’s first train murder. The victim was 69-year-old Thomas Briggs, a senior clerk at the City bank Messrs Robarts, Curtis & Co. On Saturday 9 July he had worked as he always did until 3 p.m. and then visited a niece in Peckham before making his way home by train.

No one knows just what happened in the first-class carriage of the 9.50 p.m. Fenchurch Street service. It was, in common with many other carriages, sealed off from other travellers. There were six seats, three on each side, and two doors in a design reminiscent of stagecoaches. Subsequent passengers found the empty seats covered in blood and an abandoned bag, stick and hat. Almost simultaneously, a train driver travelling in the other direction saw a body lying between the tracks. After he raised the alarm the badly injured Mr Briggs was carried to a nearby tavern but he died later from severe head injuries.

There was a public outcry at the killing, although crimes like theft and even assault had been carried out on trains almost since their inception. Now, however, a sense of peril accompanied train travel as never before.

At first there seemed little for detectives to go on. Mr Briggs’s family identified the stick and bag as his but the hat was not, and his own hat was missing. Cash was left in his pocket but his gold watch and chain were gone.

A wave of scandalised press coverage yielded the first clue. It alerted a London silversmith, appropriately called John Death, who told police he had been asked to swap Mr Briggs’s watch chain for another, and described the customer making the request. Later, a Hansom driver confirmed that a box with the name Death written on it was at his house, brought there by a German tailor, Franz Muller, who had been engaged to his daughter. The Hansom driver obligingly produced a photo of Muller and the silversmith confirmed him to be the watch-chain man.

Before a warrant could be issued for his arrest, Muller had boarded the sailing ship Victoria bound for New York in anticipation of a new life in America. Detective Inspector Richard Tanner, along with his material witnesses, soon booked tickets aboard the steamship City of Manchester, easily beating the Victoria to its destination. In fact, the Metropolitan Police party had to wait four weeks for it to catch up. When the police finally approached Muller on the dockside he asked, ‘What’s the matter?’

© Mary Evans Picture Library

A report, taking the form of verse, on the murder of Thomas Briggs in a railway carriage on 9 July 1864.

A swift search established he was in possession of Mr Briggs’s watch and remodelled hat. At the time, relations between Britain and America – torn by civil war – were strained. Nonetheless, a judge agreed to extradite Muller and he was soon brought back to England.

Muller maintained his innocence throughout his Old Bailey trial and claimed he bought the watch and hat on the London dockside. He was small, mild-mannered and apparently lacked a motive. There were also witnesses to say Mr Briggs was seated with not one but two men on the night he was killed. But the jury took just 15 minutes to find Muller guilty.

Despite pleas for clemency from the Prussian King Wilhelm I, Muller was publicly hanged at Newgate Prison just four months after the crime. Later the prison chaplain claimed his final words were ‘I did it’. Still, his death nearly resulted in a riot, with many Londoners filled with doubt about the verdict.

The savage killing of Thomas Briggs resulted in new legislation, introduced in 1868, which made communication cords compulsory on trains. Although open carriages were still viewed unfavourably it was felt Mr Briggs’s life could have been saved if the train driver only knew he had been in difficulties.

In 1897 an American journalist, Stephen Crane, travelled on the Scotch Express between London and Glasgow, and revealed that, some 30 years after the death of Mr Briggs, communication cords were causing unforeseen difficulties. The problem arose when dining cars came into use and shared the same alarm system, causing confusion. He wrote:

…if one rings for tea, the guard comes to interrupt the murder and that if one is being murdered, the attendant appears with tea. At any rate, the guard was forever being called from his reports and his comfortable seat in the forward end of the luggage van by thrilling alarms. He often prowled the length of the train with hardihood and determination, merely to meet a request for a sandwich.

Moved by Mrs Briggs’s plight, spy holes were drilled in carriage partitions by some train companies, and became known as ‘Muller lights’. Bizarrely, Mr Briggs’s reshaped hat became something of a fashion item.