По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

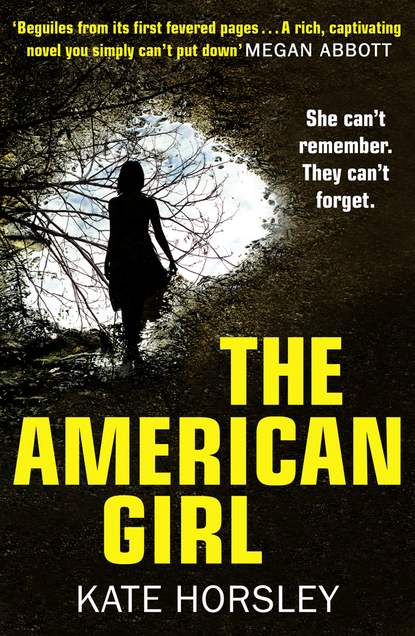

The American Girl: A disturbing and twisty psychological thriller

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I said, “Go away, Bill, I’m on holiday,” but I found myself thinking about that American girl, all the more so because the video was impossible to get away from.

Of course, the other journalists will state the obvious: the facts, the theories, the local gossip. But this is American Confessional—“the truths no one wants you to hear”—podcast once a week on iTunes in a series of audio episodes topped and tailed with our melancholy signature music. We’re interested in the big themes: police brutality, political corruption, contemporary loneliness in the toxic age of the internet. We’ve gathered quite a following for unpicking the kind of unsolved mysteries that fascinate the American listener (well, the HBO-loving, New Yorker–reading kind). I like to think the show’s motif of moral inquiry emerges through the interviews I do. I don’t judge or comment. Bill and I let our audience decide the guilt of those involved as if they were investigating each case from the comfort of their armchairs.

So we’re going for more of a think piece on this one: a young American girl coming of age, going into the world on her own only to encounter the unkindness of a stranger. Then cue the ominous music, delving into her life via her social media profile and those that encountered her here. I could see how it would work with our show, too: ragging on law enforcement always draws listeners, so we could condemn the local police, too corrupt or incompetent to find the guy in the car or examine the video before it spawned a legion of online vigilantes.

I was also the only journalist with enough guts to sneak into that hospital and make my way past the nuns. As a former Catholic-school girl, I’m not scared of nuns, which served me well when I encountered the severe-looking nun manning the hospital’s reception desk. When I asked what room Quinn Perkins was in, she muttered something dismissive in French. I could see she was tough, probably prides herself on getting rid of people; but then, I pride myself on being a professional liar.

“Could you please repeat that in English?” I said with a smile, holding my ground.

“Family only allowed here,” she barked, “no person else.” Then she paused, glaring at me over her half-moon specs. “You are a family member of Quinn Perkins?”

What, because we’re both blond and American? I thought. It was lucky for me that she made that assumption. A little too lucky perhaps. I fought off the impulse to look over my shoulder when I smiled back at her and answered, “Yes.”

Molly Swift (#ucaff2cac-5f20-5a5e-9842-b67e7aa2be31)

JULY 30, 2015

I felt bold in my lie, but I expected to be found out any moment. I followed the receptionist’s directions to the girl’s room as quickly as I could without looking as if I was hurrying. I came to the room, and stopped at the threshold.

From the newspaper stories, I’d imagined she would be in a tent of plastic, tangled in tubes and wires, barely visible; but she lay unfettered by machinery, neatly tucked under starched white sheets. Her face was bruised from the accident, her head shaved on one side. A run of stitches tattooed her scalp like railroad tracks: the place the car hit, the blow that knocked her clean from this world into dreamland, some gray space where she couldn’t be reached.

It always happens when I’m working on a new story: that moment when the person I’ve been researching transforms from a news item into a human being. I’m used to it, so I’m not sure why it hit me harder this time. Maybe because I was far from home and she was, too: the girl in the bed, the girl called Quinn Perkins, was all too real to me now. Bill had told me to take some footage with the little hidden camera he bought me years ago for my undercover work. It was pinned to my lapel, switched on and filming. He’d asked me to find a chart if I could and photograph that—to document the room, the nuns, the state the girl was in.

Instead, I found myself turning off the camera and, almost as if in a dream myself, falling into the plastic bucket seat next to her bed. I sat watching the rise and fall of her chest, even and slow, and felt a strange peace descend, like watching a child sleep. With her bruised face, her half-shaven head, and black scabs crusting the stitches, she looked worlds away from the fresh-faced teen in the photographs.

I found myself pondering all over again how she came to be walking out of the woods that gray July morning. I imagined how her legs would have been bare and dirty, her feet cut to shreds when she wandered down the middle of the dirt road, her blond hair stringy with blood. Why? This question intrigued me far more than the driver of the car.

The video footage the German tourists took of her was so shocking it looked like something from a handheld horror movie. That, and the mystery of her identity, seemed to be why the video spread so far so fast. Stills taken from clips ended up on the front pages of French papers. Soon “La fille Américaine inconnue” bled through Reuters and Google Translate, becoming “Mysterious American Girl Found.”

Eventually her father, on holiday in Tahiti with his very pregnant fiancée, recognized the face of his daughter and called up to claim her. She was given a name: Quinn Perkins of Boston. She had come to St. Roch as part of a study abroad program that placed her with a local family called the Blavettes—a schoolteacher mom, her son and daughter—presumed to be away visiting an ailing relative in some mountain area with no phone reception. Their name came out when the police released details of the case.

The news feed on my phone said Quinn was running out of time, that after the first twenty-four hours of a coma the chances of waking plummet. From the chart at the end of her bed, I could see that this particular coma had been rated a “7.” Google told me that made her chances of recovery about fifty-fifty. She should have had relatives there, talking to her, playing her music, stroking her hand. But the visitor list near the door told me she had no one—Professor Perkins hadn’t yet rushed to her side, which was odd. Not just odd, heartbreaking. A plane would get him here quickly from anywhere in the world.

They say that sometimes the feeling of touch, the sound of speech, can jolt a person from this dream state, wake them like a kiss in a fairy tale. And so I found myself reaching for her hand, taking it in mine. I touched her hand almost reverently. Time unspooled until I didn’t know how long I’d been in that room with the softly bleeping machines, the sleeping girl, her mystery sealed inside, pristine. All of a sudden, her hand twitched, the fingers wriggling inside mine. I squeezed it again, but this time nothing happened. Still, I couldn’t help thinking, She moved.

“Only you know how you got here,” I said softly.

A hand touched my shoulder. As startled as if I’d been sleeping myself, I looked up to see the habit of a nun, crisp white folds around a surprisingly young face.

The nun’s brow was creased. Her pale eyes looked nervously down at me through frameless specs. “Poor thing, she has been alone. We are so glad her family is here finally.”

“Yeah.” I smiled, hoping she didn’t want to know exactly what family I was.

She checked the charts, the machines, making little ticks on a chart as she did. Faintly, I heard her singing a French song under her breath. I sat tensed, wondering if I should make my excuses now and leave before she started asking me questions I couldn’t answer.

She was in the middle of adjusting Quinn’s sheets when she turned to me and said in very precise English, “Have you heard? It is so terrible. Now they think the family of Blavette is missing.”

“The family she was staying with?” I asked, managing to sound genuinely shocked because I was. “I thought they were visiting some relative.”

“No indeed. The grandmother has been in touch and has not seen any of them since Christmastime. The police have just searched their house again and found something perhaps, because they are putting out a news bulletin to say this family is missing. It is on the television now.”

In the reception area, a crowd had formed around the television. I couldn’t see the images except for a flicker of color between their heads, but I understood enough of the rapid French reportage to confirm the nun’s story: the Blavettes had been declared missing. The search was on for them as well as the hit-and-run driver. Two mysteries to solve for the price of one. When I walked into the hospital parking lot, I noticed that most of the other hacks had gone, perhaps to the gendarmerie to hear the press release. I had other plans.

Quinn Perkins (#ucaff2cac-5f20-5a5e-9842-b67e7aa2be31)

JULY 12, 2015

Blog Entry

It’s midnight. The family is out. Noémie’s at a party in the woods. Madame Blavette is on her date with Monsieur Right. I’m alone in the house in the middle of the French countryside, tucked into my lumpy bed that smells of bleach and jam and sterilized milk. A latchkey kid still, just in a different country. Through the slats of the wooden shutters, I can hear cicadas thrum, a thick carpet of sound, unbroken. It’s comforting somehow, though I’m almost too sleepy to work on the blog, sleepy and a bit drunk still, from cider and beer and cheap rosé all swilling together.

My phone beeps: one new message. I see the number and the knots of my spine draw closer together. The sweat on my face and chest grows cold. That number. It’s the one I mentioned a couple of posts ago, the one you guys all said you were worried about (I remember loserboy38 suggested adding it to Contacts under “Stalker,” but that was too creepy, even for me). So anyway, consequently it just comes up as just a series of ones and nines and fours and sevens. Sometimes the number series sends texts, photos like that one I posted up Thursday—the blurry photo of me sunbathing. There was another: my hoodie up, my school bag on my shoulder, and my sneakers kicking up dust on the road back to the schoolhouse. It creeped me out too much to post.

This time, it’s just a single emoji, a winking face. I delete the whole message thread, like always, and at that moment, a notification pops up, a Snapchat from lalicorne, some random person I only half remember adding a week or so ago because I thought it was a friend of Noémie’s. But they haven’t chatted me yet and the profile image is one of those gray mystery man icons so you can’t even tell if it’s a boy or a girl. I open the app and swipe onto the chat thread to see what they’ve sent.

I tap on the pink square and a video loads. The film is dark, hard to see, but I hear a noise like heavy breathing. A muffled scream startles me. I grip the phone harder. A girl’s face appears, too close up to see in detail. The film is choppy and moves so fast it’s hard to take in before the timer in the top right corner counts down. The girl’s breathing hard and there’s something—a plastic bag, maybe—stretched over her face. Three … two … one, and the screen goes black, the video vanishing forever as Snapchat deletes it and, with it, the girl.

For a long time after that I sat on the floor. The curtains were open and outside I could hear the constant cricket machine, see star-shine countryside black with no light pollution to reassure me that I was anything other than alone. Mme B says this place is haunted. I don’t think I believe in that stuff, but sitting there alone in the middle of the night, I knew what she meant, like I could almost hear the laughter of the people who lived here before trapped in the walls, behind the brick, the ghost of a good time.

I started to make up explanations to comfort myself—that it’s Noémie’s doing, a practical joke or some really weird junk mail. After a long while, I reached for the phone, half hoping it was all some weird dream, half wanting to see it again and find out that it’s really just a clever advertising campaign for a new handheld horror movie. But somehow I know it wasn’t a horror flick clip. It was too real for that. When I do pick up the phone, the video’s gone. Snapped into an untimely death in the virtual void, because it’s Snapchat, of course. All messages are instantaneous, ticking down the moments it takes you to read or watch them like a fuse on a bomb and then they’re gone.

She’s gone, as if she was never there, and I’m sitting with my back against the door, typing this on my blogging app. And here’s a straw poll: What do I do, guys? Who do I tell? Anyhow, I need to go now, to check the house, to lock the door. Something instead of sitting on the floor, feeling scared and alone in the middle of nowhere, waiting for them to come home.

Molly Swift (#ucaff2cac-5f20-5a5e-9842-b67e7aa2be31)

JULY 30, 2015

As I drove along the dusty main road of St. Roch, my skin still hummed from the excitement at the hospital: being mistaken for a relative, the plot twist with the Blavettes, seeing Quinn. I came to the part of the road she must have walked along, the jagged points of trees looming like arrowheads dug from a riverbed.

In the YouTube clip, right before the accident, Quinn makes no effort to dodge the car hurtling her way. Afterwards, she lies in the road, mumbling words you can’t quite catch from the choppy audio as the tourists got close to her, filming all the time, though a number of comment threads have speculated on what she was saying. Heading towards the line of trees, I couldn’t visualize the pixelated image of her prone body that was reprinted in all the papers. In my mind’s eye, she shimmered as she walked out of the forest, her pale fingers beckoning me on to the dark trees.

My rental car squealed around a turn in the road and towards the house. I wasn’t yet used to driving on these kinds of roads; it amazed me that I could be in town one moment and the next in the heart of farmland, driving down little sewage runnels between rows of squat olive trees or lavender or yellow rapeseed flowers. The Blavette house came after a turnoff for just such a nothing little lane. Opposite it was an orchard, where the apples were growing red and dark and glossy as poison fruit. A sprayer moved between trees, dispensing real poison that ran into drainage ditches and misted the air. This was the place where the American girl had been staying, where her vanished host family had lived for generations—it wasn’t hard to find. Google, the great democratizer of freelance detective work, told me where to go for a bit of trespassing.

I stopped the car and lit a cigarette, hoping the air around me wouldn’t catch fire in the fug of pesticide. I smoked hard, letting the engine idle while I sized up the house. Like Quinn, it was different from the pictures I’d seen, idyllic shots that must have been stolen from some holiday rental catalog. Paler, sadder, more elegant, and more ruined, it peered from between the trees, a witness to who knows what.

From my left came a rhythmic clipping noise. I climbed out of the car, keys clenched between my fingers Boston walk-to-your-door-from-the-bar style, cigarette hanging from my mouth.

An old man ambled from the side of the house carrying a pair of garden shears. He was ancient and white-bearded, clipping away at the leaves of a vine climbing the side of the house, and at first he didn’t see me. Like some scene from a French Pathé reel, he was timeless, whistling to himself as if nothing untoward had happened in the village of St. Roch. I got back in my car and crawled over the pebbles of the drive, slowly so I wouldn’t give him too much of a fright.

He must have been pretty deaf, because it took him a long time to turn around. But when he did, he looked more scared than I was when I spotted him. I let out a sigh, laughing at myself for succumbing to the gothic fantasy the place suggested. He nodded to me. I got out of the car and walked over and for a moment we stood and looked at each other, caught in the embarrassing free-fall between people who never listened in language class.

Eventually I broke the silence, introducing myself in shaky high-school French. “Bonjour. Je m’appelle Molly.”

“Ah, bonjour.” The man took off his floppy cloth hat and held out his hand, gnarled and thorn-tracked as my grandpa’s were. “Monsieur Raymond. Enchanté.” He murmured more words to me in a sweet old man crackle. Their meaning was lost on me, but I gathered from his accompanying gestures that he hammered things here and may have recently cut something with a pair of giant scissors.

“A gardener?” I asked, smiling, “For the family?”

He looked at me blankly with milky blue eyes like sucked sweets. I wondered if maybe he didn’t speak English.