По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

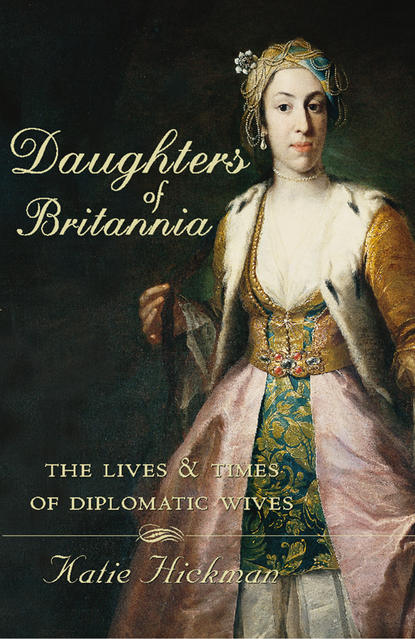

Daughters of Britannia: The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Of all the women whose experiences I have drawn upon in this book, Lady Winchilsea, who in 1661 made the long and perilous journey to Constantinople at her husband’s side, is the earliest. I am in no doubt that there were others before her, for the custom of sending resident ambassadors abroad, initiated by the Italians during the Renaissance, had begun to spread through the rest of Europe by the beginning of the sixteenth century,

(#ulink_5413a33f-d006-5025-9486-fa1ab8baa37e) but any records for them are almost impossible to find.

Even when we do have a fleeting glimpse of them (as in the case of the Countess of Winchilsea) their stories are tantalizingly elusive. Did Lady Winchilsea, like one of her more famous successors, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ever visit a harem or one of the imperial city’s glorious marble-domed hammams? Did she, like Mary Elgin nearly a century and a half later, go disguised in man’s clothing to watch her husband present his credentials to the Grand Seignior? What of the everyday practicalities of her life? What were the conditions she had to endure aboard ship? Did she have children whom she was forced to leave behind? Perhaps, like her contemporary Ann Fanshawe, she fell pregnant and gave birth thousands of miles from home. If so, did her child survive?

Although we will never know what Lady Winchilsea thought and felt when she arrived in Constantinople in 1661, remarkably, many accounts of the lives and experiences of diplomatic women have survived. Until well into the first half of this century many of them wrote letters home; these letters are often the sole record we have of them. A handful are already well-known names – Mary Wortley Montagu, Vita Sackville-West, Isabel Burton. The vast majority are not. Who was Mrs Vigor, gossiping from St Petersburg in the 1730s about the scandals and intrigues of the imperial court? Or Miss Tully, incarcerated for over a year in the consulate in plague- and famine-torn Tripoli on the eve of the French Revolution? We know almost no personal details about them (not even their Christian names). Nor do we know who their correspondents were, only that their letters were precious enough to someone, as my mother’s were to me, to have been safely kept. A great number of the sources I have used – collections of letters, private journals, or memoirs largely based on them – were never intended for public consumption at all: only a hundred or so copies were sometimes published through private subscription for family and friends. Why did they write these letters? No doubt they longed for news from home; but perhaps they also felt compelled to describe the circumstances of their lives abroad – so exhilarating, so strange, so inexplicable – to their family and friends. In Moscow in 1826 Anne Disbrowe enjoys the festivities which took place at the coronation of Tsar Nicholas I; in Peking, some fifty years later, at the heart of the Forbidden City itself, Mary Fraser takes tea with the legendary Chinese Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi; while at the turn of this century, during her seventeen long years in Chinese Turkistan, Catherine Macartney witnesses not one, but two full eclipses of the sun.

Others have more perilous tales to tell, of famines, plagues, tempests, earthquakes, wars, kidnappings, assassination attempts, and of the illnesses and deaths of their children. Even today – perhaps especially today – the world remains a hostile place for many diplomats. Their families, my own included, have often felt that the real substance of their lives is greatly, and at times almost wilfully, misunderstood. As one wife recently wrote in the BDSA (British Diplomatic Spouses Association) Magazine: ‘All Britons KNOW that diplomatic life is one long whirl of gaiety (they have seen the films and read the books)…’ Although this may be true for a few, most of the women represented here have very different stories to tell. ‘I shall never forget the utter despair into which the sight of my new home plunged me,’ wrote Jane Ewart-Biggs of her arrival as a young wife at her first posting in Algiers. From the outside their house – the central block of the old British hospital – seemed solid enough, but the interior was in a state of total disrepair, the paint flaking from the walls and doors hanging on single hinges. In the entrance hall a huge hole gaped through the ceiling ‘through which pipes and wires hung like intestines’. By the time her husband Christopher came home she was in tears. He, by contrast, was buoyed up by the fascinating day he had spent learning all about his new job. ‘It was then that I realised that the major problems arising from our nomadic life were going to affect me rather than him,’ Jane wrote, ‘and that the same circumstances creating political interest for him would make my life especially difficult.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever the external circumstances, for the most part these are personal stories told from within. Their sphere is essentially domestic. Whether they are writing from Persia or St Petersburg, these women (mostly wives, but some daughters and sisters, too) describe the concerns of any ordinary Englishwoman: children, dogs, gardens, houses, servants, clothes, food. Politics, except on the occasions when they came into direct conflict with their lives, are only incidentally discussed. What they engage with instead is daily life. For the contemporary reader the women’s subjectivity has a peculiar veritas which is frequently absent from their husbands’ more distanced and perhaps more scholarly approach. What they do, brilliantly, is to describe what life was really like. It is this, more than anything else, which is their particular genius.

Who, today, would want to read Colonel Sheil’s ponderous ethnographic dissertation on Persia in the mid-nineteenth century?

(#ulink_6cbedbad-6b7f-518b-8e9f-28f4d9892d98) The memoir of his wife Mary, however, contained in the same volume, while politically almost entirely uninformative, has a freshness and drama which remains undimmed by time. Mary vividly describes her agonizing 1,000-mile journey with three small children and an invalid husband through the Caucasus Mountains from Tehran to Trebizond on the Black Sea (from whence they were able to sail to England). She recorded with simple stoicism how they waded up to their knees through the freezing snow, eating only dry crusts and sleeping in stables: ‘I learned on this journey that neither children nor invalids know how much fatigue and privation they can endure until they are under compulsion.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In writing Daughters of Britannia I have drawn on the experiences of more than 100 diplomatic women. Their lives span nearly 350 years of history, and encompass almost every imaginable geographical and cultural variation, from the glittering social whirl enjoyed by Countess Granville in Paris after the Napoleonic Wars, to the privations suffered at the turn of this century by that redoubtable Scotswoman, Catherine Macartney, who in her seventeen years in Kashgar, in Chinese Turkistan, saw only three other European women.

Many of these women lived unique lives. Some saw sights which no other English person, man or woman, had ever seen. And yet, despite their vast differences – in character and taste as much as circumstances – a bond of shared experience unites them; a diplomatic ‘culture’ which was both official and intensely personal. Even though they are separated by nearly 200 years, when the anguished Countess of Elgin writes about her longing for news from home, it could be my own mother writing.

Dearest Mother,

Do not expect this to be an agreeable letter. I am too much disappointed in never hearing from home; the 17th July is the last from you, almost six months!… I can’t imagine why you took it into your heads that we were going home; for I am sure I wrote constantly to tell you that we were at Constantinople, and why you would not believe me I know not. If you knew what I felt when the posts arrive and no letters for me, I am sure you would pity me. I shall write to nobody but you, for I feel I am too cross.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the Elgins’ day the journey from England to Constantinople was not only long and arduous, it was also hazardous. Messengers were frequently attacked and robbed, and every single precious letter either destroyed or lost. Amazingly, even in the late twentieth century the non-arrival of the bag has been the cause of as much disappointment and pain. Here is my mother to my brother on 23 May 1978: ‘Darling Matthew, Boo hoo! The bag has let us down, and there is gnashing of teeth here, and blood is boiling.’ And to myself, on the same day: ‘Darling Katie, The bloody bag has let us down yet again and we have no letters from any of you. We are so mad we could spit …’

What qualities were needed in a diplomat’s wife? In Mary Elgin’s day nobody would have thought it necessary to enumerate them. Of course, plenty was written on the qualities required in a man. In the sixteenth century, when the idea of sending a resident ambassador abroad was still fairly new, these were frequently listed in treaties and manuals. A man (in Sir Henry Wotton’s famously ambiguous phrase) ‘sent to lie abroad for the good of his country’ was required to have an almost impossibly long list of attributes. He should be not only tall, handsome, well-born and blessed with ‘a sweet voice’ and ‘a well-sounding name’,

(#litres_trial_promo) but also well read in literature, in civil and canon law and all branches of secular knowledge, in mathematics, music geometry and astronomy. He should be able to converse elegantly in the Latin tongue and be a good orator. He should also be of fine and upstanding morals: loyal, brave, temperate, prudent and honest.

An important ambassador’s entourage could include secretaries and ‘intelligencers’, a chaplain, musicians, liverymen, a surgeon, trumpeters, gentlemen of the horse, ‘gentlemen of quality who attended for their own pleasure’, young nephews ‘wanting that polish that comes from a foreign land’, even dancing and fencing masters. But never a wife.

The ideal diplomatic wife was more difficult to describe: ‘Just as the right sort can make all the difference to her husband’s position,’ wrote Marie-Noele Kelly rather forbiddingly in her memoirs, ‘so one who is inefficient, disagreeable, disloyal, or even merely stupid, can be a millstone around his neck.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Although there have been some magnificent millstones – Lady Townley’s infamous ‘indiscretions’ forced her husband to retire from the service – there is no doubt that all the staunchest qualities deemed necessary in men were required in their wives, too. Circumstances have often demanded of them unimaginable courage and reserves of fortitude.

This book is the story of how such women survived. It is the story of many lives lived valiantly far away from family and friends; and of the uniquely demanding diplomatic culture which sustained (and sometimes failed to sustain) these women as they struggled, often in very difficult conditions, to represent their country abroad. Although their role, in the eyes of ‘his-story’, lay very much behind the scenes, I believe that this is precisely why their testimony is so valuable: it was in coping with quite ordinary things, with the daily round of life, that their resilience and resourcefulness found its greatest expression.

My only regret is for the lives which, even after more than two years’ searching, have continued to elude me. So it is only in my imagination that I can describe for you what it must have been like for Lady Winchilsea as she sailed into Constantinople, that city of marvels, by her husband’s side that afternoon. Perhaps she, like the ambassador, was dressed in her court robes, still fusty and foul-smelling from their long confinement in a damp sea-trunk. Dolphins were still a common sight in the Bosphorus in those days, and I like to think of her watching them riding the bow-waves in front of the ship as it came into the harbour at last, the fabled city rising before them, its domes and minarets shining in the pink and gold light.

* (#ulink_e598bb9a-df58-50b3-af28-9772db73dd76) Helen Pickard, the wife of the deputy high commissioner.

* (#ulink_02c11946-32c3-5728-b670-72ceaf29008c) Manuscript copies of these documents, often written in the form of relazione (‘A narrative of …’), were considered so valuable that they often commanded large sums, even in their own time.

† (#ulink_edf155ba-002c-577c-b99e-73dd35593ad1) Previously, the role of an ambassador was usually to complete a short-term mission – to declare war or negotiate a treaty. England’s first permanent ambassador, John Shirwood, became resident in Rome in 1479. In 1505 John Stile was sent to Spain by Henry VII, where he became the first resident ambassador to a secular court. By the mid-seventeenth century the idea of permanent missions abroad was no longer a novelty in England, but neither was it a universal practice. During the Restoration (1660–68) the crown sent diplomatic missions to thirty countries, but permanent embassies to only five (France, Spain, Portugal, the United Provinces and the Hanse towns of Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck). Turkey and Russia were in a special category: ambassadors were sent there in the name of the monarch, but were in fact paid servants of the Turkey Company or British merchants settled in Moscow.

* (#ulink_cc7f4ca4-e4bd-5619-8e13-eb755fa842b4) Colonel Sheil was the British minister in Tehran on the eve of the Crimean War.

Prologue (#ulink_2ee89399-4f0f-577b-8756-d68810a9a5d4)

It was the late afternoon when His Excellency the Earl of Winchilsea, Ambassador Extraordinary from King Charles II to the Grand Seignior Mehmed IV, Sultan of Sultans and God’s Shadow upon Earth, sailed into Constantinople.

To arrive in Constantinople by sea, even today, is to be presented with an extraordinary sight. In 1661 it was one of the wonders of the world. Built on seven hills, and surrounded on three sides by water, it was described by contemporary travellers as not only the biggest and richest, but also the most beautiful city on earth. The unequal heights of the seven hills, each one topped with the gilded dome and minarets of a mosque, made the city seem almost twice as large as it really was. On each hillside, raised one above the other in an apparent symmetry, were palaces, pavilions and mansions, each one set in its own gardens, surrounded by groves of cypress and pine. On the furthermost spit of land, and clearly visible from the sea, was the Seraglio,

(#ulink_052b914f-8c69-5454-99c3-4b2b1968828e) the Sultan’s palace, its turrets and domes reflected in the waters of the Bosphorus.

Few buildings in history have had the sinister beauty of this fabled pleasure dome. No contemporary Christian king, and only a few since, had aspired to anything that equalled it. Built around six great courtyards, and covering as much land as a small town, this city within a city was the focus of all life in Constantinople. The Seraglio was not only the symbol of all power in the great Ottoman empire but also, to the dazzled imagination of foreign travellers, the seat of all pleasures too. For it was here, too, that the Grand Seignior’s harem was incarcerated – several hundred concubines, beautiful slave girls bought from as far away as Venice, Georgia and Circassia and kept, out of sight of other eyes, for the Sultan’s delight alone.

Here, every day, as many as 10,000 people were catered for – including the four corps of guards who protected the Seraglio, the black and white eunuchs, the palace slaves, its pages, treasurers, armourers, grooms, physicians, astrologers and imams, as well as the Sultan and his family. According to one estimate there were 1,000 cooks and scullions working in the palace kitchens which, in addition to staples such as meat and vegetables, produced jams, pickles, sweetmeats and sherbets in quantities ‘beyond possibility of measure’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Opposite the Seraglio, and close enough to be easily visible from it, rose the graceful shores of Asia, a pleasing prospect of wilderness interspersed with villages and fruit trees. And on the narrow stretch of water in between them sailed the water traffic of the world.

It was three months since the ambassador’s entourage had set sail, and the journey had not been an easy one. On New Year’s Day, just after they had left Smyrna on the last leg of their voyage, a tempest had all but tossed them into oblivion. During the week of the storm their vessel had been cast upon rocks five times, leaving every man on board fearing for his life. It was an escape ‘so miraculous and wonderfull, considering the violence of the storm, the carere and weight of our ship, as ought to make the 8 day of January for ever to be recorded by us to admiration, and anniversary thankfulness for God’s providence and protection,’ wrote one witness.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Now, the ambassador’s storm-battered, leaky little ship – its masts, yards and decks encrusted eerily with white salt from the continual spray of the sea, its flags and ensigns flying, its guns at the ready – sailed across the last stretch of the Sea of Marmara and into the Bosphorus at last. It must have seemed to those on board as if they had reached the very epicentre of the world.

In many ways, of course, they had. Whoever controlled Constantinople controlled not only the great gateway between Europe and Asia, but also one of the greatest water trade routes linking the northern and southern hemispheres. Looking north, the Black Sea gave access through the Volga to southern Russia, and through the Danube to the Balkans and eastern Europe. To the south, the Sea of Marmara led not only to the Aegean, but to the whole of the Mediterranean, North Africa and beyond. In amongst the fishing boats and the caiques, the galleons and perhaps even one of the Sultan’s magnificent gilded barges, sailed innumerable vessels from all four corners of the earth – merchant ships, slave galleys and vast timber rafts cut from the deep forests of southern Russia and floated down the Bosphorus for shipbuilding and fuel.

On the captain’s orders the men lined the rigging, their muskets at the ready. As the ship drew close to the Sultan’s palace, in a suffocating cloud of gunpowder, a salutation of sixty-one guns was fired. A little while later, when the ambassador finally disembarked, it was to a second deafening salute of fifty-one guns. His welcoming committee comprised not only his own servants, English merchants, and other travelling companions brought with them from Smyrna, but also many of the Grand Seignior’s officers who had come to honour him. Their procession was so splendid that multitudes of people flocked from all parts of the city to watch them, and made ‘the business of more wonder and expectation’. ‘As we marched all the streets were crowded with people and the windows with spectators, as being unusual in this countrey to see a Christian Ambassadour attended with so many Turkish officers,’ wrote the ambassador’s secretary. He was so proud of their ‘very grand equipage’ – believing that ‘none of his predecessours, nor yet the Emperour’s Ambassadours, can boast of a more honourable nor a more noble reception’ – that he recorded each element:

1. The Vaivod

(#ulink_a471ef36-7575-54b6-a229-67e24730e4f2) of Gallata and his men

2. The Captain of the Janizaries with his Janizaries

3. The Chouse Bashaw with his Chouses

(#ulink_47fb461d-676c-5265-8be1-c9f232307fb8)

4. The English Trumpeters

5. The English horsemen and Merchants

6. My Lord’s Janizaries

7. The Druggerman

(#ulink_bf97b894-1da9-5477-9583-8e61ccb9bff6)