По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

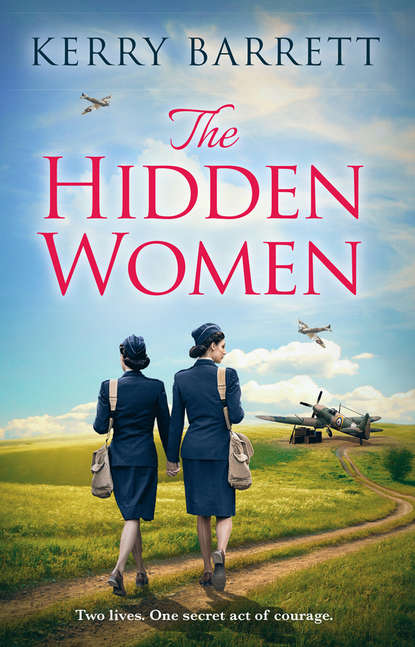

The Hidden Women: An inspirational novel of sisterhood and strength

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Miranda butted in and I almost tutted because I was enjoying having Jack’s attention.

‘She’s an expert in Victorian painting and she’s often on those daytime antiques shoes. She’s brilliant, actually, on screen. She’s so enthusiastic and because she’s been a university lecturer forever she explains things really well. She writes books, too. We’re very proud of her, because it’s not been easy for her.’

Jack was staring at Miranda. ‘I know her,’ he said, excitedly. ‘She’s got hair just like you but in a cloud round her face, right?’

Miranda laughed. ‘That’s her,’ she said. ‘And she wears glasses like Helena’s.’

I pushed my black-rimmed specs up my nose and grinned. ‘I don’t have the hair,’ I said, gesturing to my own poker-straight style. ‘But I did inherit the dodgy eyesight.’

I felt we were giving Jack an unfair picture of our mother so I carried on. ‘Mum’s wonderful. She’s a brilliant grandmother to Dora, and Miranda’s little boy. She’s helped me out so much. I wouldn’t have been able to go back to work without knowing she was round the corner.’

Miranda nodded. ‘She is fab,’ she said. ‘We’re lucky she got over her depression and that it never came back – not like it was.’

‘And what about your dad?’

I felt a bit like Jack was researching us rather than me him, but somehow I didn’t mind.

‘Dad’s a composer,’ Miranda said. ‘He writes music for films and TV shows, and adverts sometimes too.’

I shifted in my seat. ‘He did some of the music for Mackenzie,’ I said, wondering if I should have mentioned this before. ‘Not the theme but some of the incidental music.’

He gaped at me in astonishment. ‘No,’ he said. ‘My Mackenzie?’

‘The very same.’

Jack chuckled. ‘Isn’t it a small world, eh?’

‘Isn’t it,’ said Miranda. ‘Dad’s career was just taking off in the Nineties, when we were growing up. He worked long hours. And when Mum got ill, he wasn’t completely able to cope with four kids.’

Jack nodded. ‘And Lil?’

‘She was a musician, like Dad,’ I told him. ‘Piano, mostly, but she’s the sort of person who can play anything. She was a session musician and she travelled all over the world playing with different bands or singers. Six months on a cruise ship here, a year in a jazz club in New York, there. Recording an album with the Rolling Stones one day, hanging out with Fleetwood Mac the next.’

‘Sounds incredible.’

‘She’s got some brilliant stories,’ I agreed.

‘But when we were kids and Mum was poorly,’ Miranda said, ‘Lil stepped in and made sure we were being looked after.’ She drained her wine glass. ‘I’m not sure what we would have done without her.’

‘Blimey,’ Jack said, topping up Miranda’s empty glass. ‘You are really close?’

I nodded. ‘I thought so,’ I said. ‘And yet she’s never mentioned her time in the ATA.’

I looked at Miranda. ‘Manda, we found Lil’s service record.’ I picked up the folder Jack had brought with him, which was now splattered with beer and something that looked like tomato ketchup, even though we’d not eaten. ‘Look at what happened.’

I handed her the sheet of paper and watched as she read the lines at the bottom.

‘Oh shit,’ she said. ‘Dishonourable discharge?’

‘What do you think, Manda?’ I said. ‘Do you still think we should speak to her about it?’

Miranda made a face. ‘I’m going to Paris on Friday for a week,’ she said. ‘So I can’t help. But yes, I think you should go and see her. Find out what it was all about.’

‘She might not want to talk,’ I said. ‘What if it upsets her? She’s really old.’

‘She’s tough as old boots,’ said Miranda. ‘I really think you should try to talk about it. We can’t pretend that we don’t know now – she’d see through that in a flash.’

I nodded. That was true.

‘All right,’ I said. ‘I’ll go and see her at the weekend.’

Chapter 12 (#ulink_99b5b0f6-8a9e-5e54-b6ec-ebca0b143459)

The following Saturday, Dora and I sat on a train heading out through the leafy suburbs of south-west London to see Lil. She was ninety-four now and very frail, so she lived in a care home. It was an amazing place, funded by an entertainers’ charity. All the residents of the home had once made their living as performers of one kind or another and now saw out their days reminiscing together and – too often for my liking – providing their own entertainment. They had mostly been jobbing actors, or, as Lil had been, session musicians, but there was the occasional recognisable face and they all loved to put on a show.

I normally phoned ahead when I visited, but today I’d not told Lil I was coming. After everything we’d found out, I was nervous about seeing her, which was strange considering how much I loved her. And for some reason I didn’t want to warn her – though quite why I needed to be so sneaky about it all, I wasn’t sure. It wasn’t like I was expecting to walk in and catch her piloting a Spitfire around the residents’ lounge.

What I actually found, when we walked into the residents’ lounge, was one of the actors – a man who once trod the boards at the RSC and had been a regular on the West End stage – standing in the middle of the room, reciting a speech from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

I paused by the door, scanning the room for Lil and clocked her sitting in the corner watching the ageing actor with barely disguised amusement. Our eyes met and she smiled.

‘Hello,’ she called, ignoring the fact that the actor was still going. ‘I wasn’t expecting you today.’

Dora jumped up and down. She loved Lil. ‘Hello!’ she shouted. ‘’Lo, Lil!’

Like a small bullet, she swerved the gesturing arms of the Shakespearean chap, and hurtled over to my aunt. I followed and sat down next to her.

‘Surprise!’ I said. ‘Careful of Lil’s legs, Dora.’

Dora clambered up on to my knee and beamed at Lil. ‘’Lo, Lil,’ she said again.

‘Hello, my darling girl,’ Lil said to her, twirling one of her curls round her finger. ‘I think you’ve grown again.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: