По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

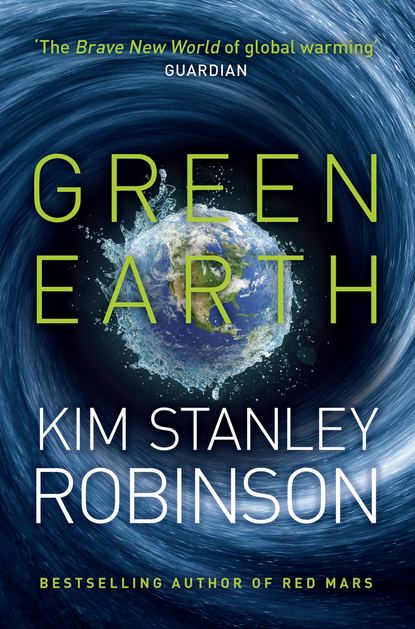

Green Earth

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Well, in a way they’re right. There’s no reason me doing it should be anything special. It may just be me wanting some strokes. It’s turned out to be harder than I thought it would be. A real psychic shock.”

“Because …”

“Well, I was thirty-eight when Nick arrived, and I had been doing exactly what I wanted ever since I was eighteen. Twenty years of white male American freedom, just like what you have, young man, and then Nick arrived and suddenly I was at the command of a speechless mad tyrant. I mean, think about it. Tonight you can go wherever you want to, go out and have some fun, right?”

“That’s right, I’m going to go to a party for some new folks at Brookings, supposed to be wild.”

“All right, don’t rub it in. Because I’m going to be in the same room I’ve been in every night for the past seven years, more or less.”

“So by now you’re used to it, right?”

“Well, yes. That’s true. It was harder with Nick, when I could remember what freedom was.”

“You have morphed into momhood.”

“Yeah. But morphing hurts, baby, just like in X-Men. I remember the first Mother’s Day after Nick was born, I was most deep into the shock of it, and Anna had to be away that day, maybe to visit her mom, I can’t remember, and I was trying to get Nick to take a bottle and he was refusing it as usual. And I suddenly realized I would never be free again for the whole rest of my life, but that as a non-mom I was never going to get a day to honor my efforts, because Father’s Day is not what this stuff is about, and Nick was whipping his head around even though he was in desperate need of a bottle—and I freaked out, Roy. I freaked out and threw that bottle down.”

“You threw it?”

“Yeah. I slung it down and it hit at the wrong angle or something and just exploded. The baggie broke and the milk shot up and sprayed all over the room. I couldn’t believe one bottle could hold that much. Even now when I’m cleaning the living room I come across little white dots of dried milk here and there, like on the mantelpiece or the windowsill. Another little reminder of my Mother’s Day freak-out.”

“Ha. The morph moment. Well Charlie you are indeed a pathetic specimen of American manhood, yearning for your own Mother’s Day card, but just hang in there—only seventeen more years and you’ll be free again!”

“Oh fuckyouverymuch! By then I won’t want to be.”

“Even now you don’t wanna be. You love it, you know you do. But listen I gotta go Phil’s here bye.”

After talking with Charlie, Anna got absorbed in work as usual, and might well have forgotten her lunch date; but because this was a perpetual problem of hers, she had set her watch alarm, and when it beeped she saved and went downstairs. Down at the new embassy the young monk and his most elderly companion sat on the floor inspecting a box.

They noticed her and looked up curiously, then the younger one nodded, remembering her from the morning conversation after their ceremony.

“Still interested in some pizza?” Anna asked. “If pizza is okay?”

“Oh yes,” the young one said. The two men got to their feet, the old man in several distinct moves; one leg was stiff. “We love pizza.” The old man nodded politely, glancing at his assistant, who said something in their language.

As they crossed the atrium to Pizzeria Uno Anna said uncertainly, “Do you eat pizza where you come from?”

The younger man smiled. “No. But in Nepal I ate pizza in teahouses.”

“Are you vegetarian?”

“No. Tibetan Buddhism has never been vegetarian. There were not enough vegetables.”

“So you are Tibetans! But I thought you said you were an island nation?”

“We are. But originally we came from Tibet. The old ones, like Rudra Cakrin here, left when the Chinese took over. The rest of us were born in India, or on Khembalung itself.”

They entered the restaurant, where big booths were walled by high wooden partitions. The three of them sat in one, Anna across from the two men.

“I am Drepung,” the young man said, “and the rimpoche here, our ambassador to America, is Gyatso Sonam Rudra Cakrin.”

“I’m Anna Quibler,” Anna said, and shook hands with each of them. The men’s hands were heavily callused.

Their waiter appeared and after a quick muttered consultation, Drepung asked Anna for suggestions, and in the end they ordered a combination pizza.

Anna sipped her water. “Tell me about Khembalung.”

Drepung nodded. “I wish Rudra Cakrin himself could tell you, but he is still taking his English lessons, I’m afraid. Apparently they are going very badly. In any case, you know that China invaded Tibet in 1950, and that the Dalai Lama escaped to India in 1959?”

“Yes, that sounds familiar.”

“Yes. And during those years, and ever since then too, many Tibetans moved to India to get away from the Chinese, and closer to the Dalai Lama. India took us in very hospitably, but when the Chinese and Indian governments disagreed over their border in 1960, the situation became very awkward for India. They were already in a bad way with Pakistan, and a serious controversy with China would have been too much. So, India requested that the Tibetan community in Dharamsala make itself as small and inconspicuous as possible. The Dalai Lama and his government did their best, and many Tibetans were relocated, mostly to the far south. One group took the offer of an island in the Sundarbans, and moved there. The island was ours from that point, as a kind of protectorate of India, like Sikkim, only not so formally arranged.”

“Is Khembalung the island’s original name?”

“No. I do not think it had a name before. Most of our group lived at one time in the valley of Khembalung. So that name was kept, and we have shifted away from the Dalai Lama’s government in Dharamsala.”

At the sound of the words “Dalai Lama” the old monk made a face and said something in Tibetan.

“The Dalai Lama is still number one with us,” Drepung clarified. “It is a matter of some religious controversies with his associates. A matter of how best to support him.”

“And your island?”

Their pizza arrived, and Drepung began talking between big bites. “Lightly populated, the Sundarbans. Ours was uninhabited.”

“Did you say uninhabitable?”

“People with lots of choices might say they were uninhabitable,” Drepung said. “And they may yet become so. They are best for tigers. But we have done well there. We have become like tigers. Over the years we have built a nice town. Schools, houses, hospital. All that. And seawalls. The whole island has been ringed by dikes. Lots of work. Hard labor.” He nodded as if personally acquainted with this work. “Dutch advisors helped us. Very nice. Our home, you know? Khembalung has moved from age to age. But now …” He waggled a hand again, took another slice of pizza, bit into it.

“Global warming?” Anna ventured. “Sea level rise?”

He nodded, swallowed. “Our Dutch friends suggested that we establish an embassy here, to join their campaign to influence American policy.”

Anna quickly bit into her pizza, so that she would not reveal the thought that had struck her, that the Dutch must be desperate indeed if they had been reduced to help from these people. She thought things over as she chewed. “So here you are,” she said. “Have you been to America before?”

Drepung shook his head. “None of us have.”

“It must be pretty overwhelming.”

He frowned at this word. “I have been to Calcutta.”

“Oh I see.”

“This is very different, of course.”

“Yes, I’m sure.”

She liked him: his musical Indian English, his round face and big liquid eyes, his ready smile. The two men made quite a contrast: Drepung young and tall, round-faced, with a kind of baby-fat look; Rudra Cakrin old, small, and wizened, his face lined with a million wrinkles, his cheekbones and narrow jaw prominent in an angular, nearly fleshless face.