По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

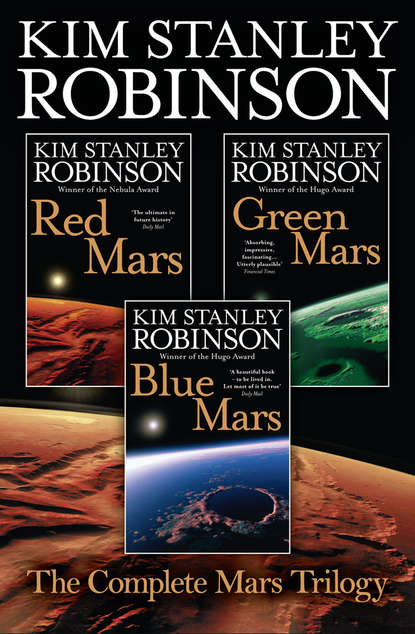

The Complete Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

No one knew.

She and Frank conferred in private. “Let’s try giving them the illusion of making the decision,” he said to her with a brief smile; she realized that he was not displeased to have seen her fail in the general meeting. Their encounter was coming back to haunt her, and she cursed herself for a fool. Little politburos were dangerous …

Frank polled everyone concerning their wishes, and then displayed the results on the bridge, listing everyone’s first, second and third choices. The geological surveys were popular, while staying on Phobos was not. Everyone already knew this, and the posted lists proved that there were fewer conflicts than it had seemed. “There are complaints about Arkady taking over Phobos,” Frank said at the next public meeting. “But no one but him and his friends want that job. Everyone else wants to get down to the surface.”

Arkady said, “In fact we should get hardship compensation.”

“It’s not like you to talk about compensation, Arkady,” Frank said smoothly.

Arkady grinned and sat back down.

Phyllis wasn’t amused. “Phobos will be a link between Earth and Mars, like the space stations in Earth orbit. You can’t get from one planet to the other without them, they’re what naval strategists call choke points.”

“I promise to keep my hands off your neck,” Arkady said to her.

Frank snapped, “We’re all going to be part of the same village! Anything we do affects all of us! And judging by the way you’re acting, dividing up from time to time will be good for us. I for one wouldn’t mind having Arkady out of my sight for a few months.”

Arkady bowed. “Phobos here we come!”

But Phyllis and Mary and their crowd still were not happy. They spent a lot of time conferring with Houston, and whenever Maya went into Torus B, conversations seemed to cease, eyes followed her suspiciously – as if being Russian would automatically put her in Arkady’s camp! She damned them for fools, and damned Arkady even more. He had started all this.

But in the end it was hard to tell what was going on, with a hundred people scattered in what suddenly felt like such a large ship. Interest groups, micropolitics; they really were fragmenting. One hundred people only, and yet they were too large a community to cohere! And there was nothing she or Frank could do about it.

One night she dreamed again of the face in the farm. She woke shaken, and was unable to fall back asleep; and suddenly everything seemed out of control. They flew through the vacuum of space inside a small knot of linked cans, and she was supposed to be in charge of this mad argosy! It was absurd!

She left her room, climbed D’s spoke tunnel to the central shaft. She pulled herself to the bubble dome, forgetting the tunneljump game.

It was four a.m. The inside of the bubble dome was like a planetarium after the audience has gone: silent, empty, with thousands of stars packed into the black hemisphere of the dome. Mars hung directly overhead, gibbous and quite distinctly spherical, as if a stone orange had been tossed among the stars. The four great volcanoes were visible pockmarks, and it was possible to make out the long rifts of Marineris. She floated under it, spreadeagled and spinning very slightly, trying to comprehend it, trying to feel something specific in the dense interference pattern of her emotions. When she blinked, little spherical teardrops floated out and away among the stars.

The lock door opened. John Boone floated in, saw her, grabbed the door handle to stop himself. “Oh, sorry. Mind if I join you?”

“No.” Maya sniffed and rubbed her eyes. “What gets you up at this hour?”

“I’m often up early. And you?”

“Bad dreams.”

“Of what?”

“I can’t remember,” she said, seeing the face in her mind.

He pushed off, floated past her to the dome. “I can never remember my dreams.”

“Never?”

“Well, rarely. If something wakes me up in the middle of one, and I have time to think about it, then I might remember it, for a little while anyway.”

“That’s normal. But it’s a bad sign if you never remember your dreams at all.”

“Really? What’s it a symptom of?”

“Of extreme repression, I seem to recall.” She had drifted to the side of the dome; she pushed off through the air, stopped herself against the dome next to him. “But that may be Freudianism.”

“In other words something like the theory of phlogiston.”

She laughed. “Exactly.”

They looked out at Mars, pointed out features to each other. Talked. Maya glanced at him as he spoke. Such bland, happy good looks; he really was not her type. In fact she had taken his cheeriness for a kind of stupidity back at the beginning. But over the course of the voyage she had seen that he was not stupid.

“What do you think of all the arguments about what we should do up there?” she asked, gesturing at the red stone ahead of them.

“I don’t know.”

“I think Phyllis makes a lot of good points.”

He shrugged. “I don’t think that matters.”

“What do you mean?”

“The only part of an argument that really matters is what we think of the people arguing. X claims a, Y claims b. They make arguments to support their claims, with any number of points. But when their listeners remember the discussion, what matters is simply that X believes a and Y believes b. People then form their judgement on what they think of X and Y.”

“But we’re scientists! We’re trained to weigh the evidence. ”

John nodded. “True. In fact, since I like you, I concede the point.”

She laughed and pushed him, and they tumbled down the sides of the dome away from each other.

Maya, surprised at herself, arrested her motion against the floor. She turned and saw John coming to a halt across the dome, landing against the floor. He looked at her with a smile, caught a rail and launched himself into the air, across the domed space on a course aimed at her.

Instantly Maya understood, and forgetting completely her resolution to avoid this kind of thing, she pushed off to intercept him. They flew directly at each other, and to avoid a painful collision had to catch and twist in mid-air, as if dancing. They spun, hands clasped, spiraling up slowly toward the dome. It was a dance, with a clear and obvious end to it, there to reach whenever they liked: whew! Maya’s pulse raced, and her breath was ragged in her throat. As they spun they tensed their biceps and pulled together, as slowly as docking spacecraft, and kissed.

With a smile John pushed down from her, sending her flying to the dome, and him to the floor, where he caught and crawled to the chamber’s hatch. He locked it.

Maya let her hair loose and shook it out so it floated around her head, across her face. She shook it wildly and laughed. It was not as though she felt on the verge of any great or overmastering love; it was simply going to be fun; and that feeling of simplicity was … She felt a wild surge of lust, and pushed off the dome toward John. She tucked into a slow somersault, unzipping her jumper as she spun, her heart pounding like tympanis, all her blood rushing to her skin, which tingled as if thawing as she undressed, banged into John, flew away from him after an overhasty tug at a sleeve; they bounced around the chamber as they got their clothes off, miscalculating angles and momentums until with a gentle thrust of the big toes they flew into each other and met in a spinning embrace, and floated kissing among their floating clothes.

In the days that followed they met again. They made no attempt to keep the relationship a secret; so very quickly they were a known item, a public couple. Many aboard seemed taken aback by the development; and one morning walking into the dining hall, Maya caught a swift glance from Frank, seated at a corner table, that chilled her; it reminded her of some other time, some incident, some look on his face that she couldn’t quite call to mind.

But most of those aboard seemed pleased. After all it was a kind of royal match, an alliance of the two powers behind the colony, signifying harmony. Indeed the union seemed to catalyze a number of others, which either came out of the closet or, in the newly supersaturated medium, sprang into being. Vlad and Ursula, Dmitri and Elena, Raul and Marina; newly evident couples were everywhere, to the point where the singletons among them began to make nervous jokes about it. But Maya thought she noticed less tension in voices, fewer arguments, more laughter.

One night, lying in bed thinking about it (thinking of wandering over to John’s room) she wondered if that was why they had gotten together: not from love, she still did not love him, she felt no more than friendship for him, charged by lust that was strong but impersonal – but because it was, in fact, a very useful match. Useful to her – but she swerved from that thought, concentrated on the match’s usefulness to the expedition as a whole. Yes, it was politic. Like feudal politics, or the ancient comedies of spring and regeneration. And it felt that way, she had to admit; as if she were acting in response to imperatives stronger than her own desires, acting out the desires of some larger force. Of, perhaps, Mars itself. It was not an unpleasant feeling.

As for the idea that she might have gained leverage over Arkady; or Frank; or Hiroko … well, she successfully avoided thinking about that. It was one of Maya’s talents.

Blooms of yellow and red and orange spread across the walls. Mars was now the size of the moon in Earth’s sky. It was time to harvest all their effort; only a week more, and they would be there.

There was still tension over the unsolved problems of landfall assignments. And now Maya found it less easy than ever to work with Frank: it was nothing obvious, but it occurred to her that he did not dislike their inability to control the situation, because the disruptions were being caused more by Arkady than anyone else, and so it looked like it was more her fault than his. More than once she left a meeting with Frank and went to John, hoping to get some kind of help. But John stayed out of the debates, and threw his support behind everything that Frank proposed. His advice to Maya in private was fairly acute, but the trouble was he liked Arkady and disliked Phyllis; so often he recommended to her that she support Arkady, apparently unaware of the way this tended to undercut her authority among the other Russians. She never pointed this out to him, however. Lovers or not, there were still areas she didn’t wish to discuss with him, or with anyone else.

But one night in his room her nerves were jangling, and lying there, unable to sleep, worrying about first this and then that, she said, “Do you think it would be possible to hide a stowaway on the ship?”