По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

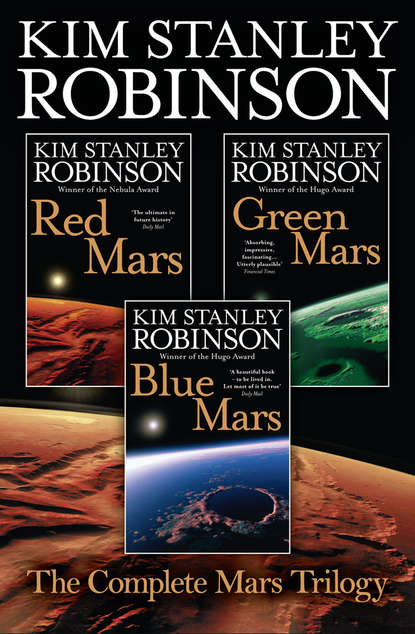

The Complete Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s a new kind of cryptogamic crust,” Vlad said when John asked him about it. “A symbiosis of cyanobacteria and Florida platform bacteria. The platform bacteria go very deep, and convert sulfates in the rock to sulfides, which then feed a variant of Microcoleus. The top layers of that grow in filaments, which bind to sand and clay in big dendritic formations, so it’s like little forest sylvanols with really long bacterial root systems. It looks like these root systems will keep on going right down through the regolith to bedrock, melting the permafrost as they go.”

“And you’ve released this stuff?” John said.

“Sure. We need something to bust up the permafrost, right?”

“Is there anything to stop it from growing planetwide?”

“Well, it has the usual array of suicide genes in case it begins to overwhelm the rest of the biomass, but if it keeps to its niche …”

“Wow.”

“It’s not too unlike the first life forms that covered the Terran continents, we think. We’ve just enhanced its speed of growth, and its root systems. The funny thing is that I think at first it’s going to cool the atmosphere, even though it’s warming things underground. Because it’ll really increase chemical weathering of the rock, and all those reactions absorb CO

from the air, so the air pressure is going to drop.”

Maya had come up and joined them with a big hug for John, and now she said, “But won’t the reactions release oxygen as fast as they absorb CO

, and keep air pressure up?”

Vlad shrugged. “Maybe. We’ll see.”

John laughed. “Sax is a long term thinker. He’ll probably be pleased.”

“Oh yes. He authorized the release. And he’s coming to study here again when spring comes.”

They had dinner in a hall located high on the fin, just under the crest. Skylights opened above to the greenhouse on the crest itself, and windows ran the length of the north and south walls; stands of bamboo filled the walls to east and west. All the residents of Acheron were there for dinner, holding to an Underhill custom as they did in many other ways. The discussion at John and Maya’s table ranged widely, but kept returning to the current work, which involved trying to solve problems caused by the need to implant safeguards in all the GEMs they were releasing. Double suicide genes in every GEM was a practice the Acheron group had initiated on its own, and it was now going to be codified as UN law. “That’s all well and good for legal GEMs,” Vlad said. “But if some fools try something on their own and blow it, we could be in big trouble anyway.”

After dinner, Ursula said to John and Maya, “Since you’re here you ought to get your physicals. It’s been a while for both of you.”

John, who hated physicals and indeed all medical attention of any kind, demurred. But Ursula hounded him, and eventually he gave in, and visited her clinic a couple days later. There he was put through a battery of diagnostic tests that seemed even more intensive than usual, most of them run by imaging machines and computers with too-relaxing voices, telling him to move this way and then that, while John in complete ignorance did what he was told. Modern medicine. But after all that, he was poked and prodded and tapped in time-honored fashion by Ursula herself. And when it was over he was lying on his back with a white sheet over him, while she stood at his side, looking at read-outs and humming absently.

“You’re looking good,” she told him after several minutes of that. “Some of the usual gravity-related problems, but nothing we can’t deal with.”

“Great,” John said, feeling relieved. That was the thing about physicals; any news was bad news, one wanted an absence of news. Getting that was somehow a victory, and more so every time; but still, a negative accomplishment. Nothing had happened to him, great!

“So do you want the treatment?” Ursula asked, her back to him, her voice casual.

“The treatment?”

“It’s a kind of geronotological therapy. An experimental procedure. Somewhat like an inoculation, but with a DNA strengthener. Repairs broken strands, and restores cell division accuracy to a significant degree.”

John sighed. “And what does that mean?”

“Well, you know. Ordinary ageing is mostly caused by cell division error. After a number of generations, ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands depending which kind of cells you’re talking about, errors in reproduction start to increase, and everything gets weaker. The immune system is one of the first to weaken, and then other tissues, and then finally something goes wrong, or the immune system gets overwhelmed by a disease, and that’s it.”

“And you’re saying you can stop these errors?”

“Slow them down, anyway, and fix the ones that are already broken. A mix, really. The division errors are caused by breaks in DNA strands, so we wanted to strengthen DNA strands. To do it we would read your genome, and then build an auto repair genomic library of small segments that will replace the broken strands—”

“Auto repair?”

She sighed. “All Americans think that is funny. Anyhow we push this auto repair library into the cells, where they bind to the original DNA and help keep them from breaking.” She began to draw double and quadruple helixes as she talked, shifting inexorably into biotech jargon, until John could only catch the general drift of the argument, which apparently had its origins in the genome project and the field of genetic abnormality correction, with application methods taken from cancer therapy and GEM technique. Aspects of these and many other different technologies had been combined by the Acheron group, Ursula explained. And the result seemed to be that they could give him an infection of bits of his own genome, an infection which would invade every cell in his body except for parts of his teeth and skin and bones and hair; and afterwards he would have nearly flawless DNA strands, repaired and reinforced strands that would make subsequent cell division more accurate.

“How accurate?” he asked, trying to grasp what it all meant.

“Well, about like if you were ten years old.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No, no. We’ve all done it to ourselves, back around Ls ten of this year, and so far as we can tell, it’s working.”

“Does it last forever?”

“Nothing lasts forever, John.”

“How long then?”

“We don’t know. We ourselves are the experiment, we figure we’ll find out as we go along. It seems possible we might be able to do the therapy again when the rate of division error begins to increase again. If that is successful, it could mean you would last for quite a while.”

“Like how long?” he insisted.

“Well, we don’t know, do we? Longer than we live now, that’s pretty sure. Possibly a lot longer.”

John stared at her. She smiled at the expression on his face, and he could feel that his jaw was slack with amazement; no doubt he looked less than brilliant, but what did she expect? It was … it was …

He was following his thoughts with difficulty as they skittered around. “Who have you told about this?” he asked.

“Well, we have asked everyone in the first hundred, when they get a check-up with us. And everyone here at Acheron has tried it. And the thing is, we’ve only combined methods that everyone has, so it won’t be long before others try putting it all together too. So we’re writing it up for publication, but we’re going to send the articles first to be reviewed by the World Health Organization. Political fallout, you know.”

“Um,” John said, considering it. News of a longevity drug loose on Mars, back among the teeming billions … my Lord, he thought. “Is it expensive?”

“Not extremely. Reading your genome is the most expensive part, and it takes time. But it’s just a procedure, you know, it’s just computer time. It’s very possible you could inoculate everyone on Earth. But the population problem down there is already critical as it is. They’d have to institute some pretty intense population control, or else they’d go Malthusian really fast. We thought we’d better leave the decisions to the authorities down there.”

“But word is sure to get out.”

“Is that true? They might try to put a clamp on it. Maybe even a comprehensive clamp, I don’t know.”

“Wow. But you folks … you just went ahead and did it?”

“We did.” She shrugged. “So what do you say? Want to do it?”

“Let me think about it.”

He went for a walk on the crest of the fin, up and down the long greenhouse stuffed with bamboo and food crops. Walking west he had to shield his eyes from the glare of the afternoon sun, even through the filtered glass; walking back east, he could look out at the broken slopes of lava stretching up to Olympus Mons. It was hard to think. He was sixty-six years old; born in 1982, and what was it back on Earth now, 2048? M-11, eleven long hi-rad Martian years. And he had spent thirty-five months in space, including three trips between Earth and Mars, which was still the record. He had taken on 195 rems in those trips alone, and he had low blood pressure and a bad HDL to LDL ratio, and his shoulders ached when he swam and he felt tired a lot. He was getting old. He didn’t have all that many years left, weird though it was to think of it; and he had a lot of faith in the Acheron group, who, now that he thought of it, were wandering around their aerie working and eating and playing soccer and swimming and so on with little smiles of absorbed concentration, with a kind of humming. Not like ten year-olds, certainly not; but with an aura of suffused, absorbed happiness. Of health, and more than health. He laughed out loud, and went back down into Acheron looking for Ursula. When she saw him she laughed too. “It’s not really that hard a choice, is it.”

“No.” He laughed with her: “I mean, what have I got to lose?”

So he agreed to it. They had his genome in their records, but it would take a few days to synthesize the collection of repair strands and clip them onto plasmids, and clone millions more. Ursula told him to come back in three days.