По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

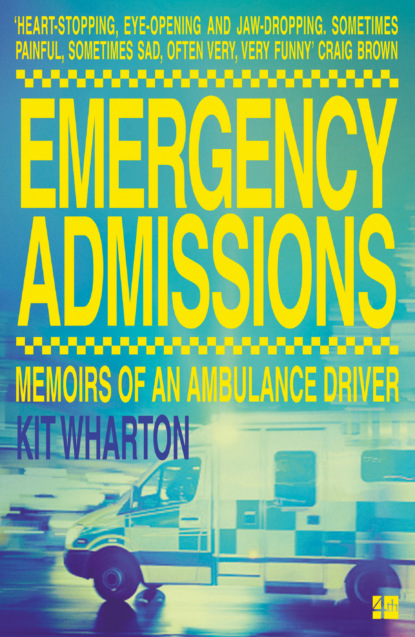

Emergency Admissions: Memoirs of an Ambulance Driver

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I try to phrase things delicately.

—Would it be fair to say your pulse might have been a little elevated by what was going on tonight?

—Well yes. Maybe we were going at it a bit strong.

—Maybe go at it a bit less strong next time?

(You should always give patients advice on how to manage their condition.)

—Yes, I think I will. Maybe give it up altogether.

Off we go.

The hospital – like a lot of them – appears to have been designed by a child with attention deficit disorder, the architect having an epileptic fit. Departments, corridors, lifts and wards all over the place, in no order at all. To get from one side to the other you have to take two different lifts, and cross a street. You could lose an army in here.

We take the patient to A&E, and hand her over to Fatima, one of the regular triage nurses. Triage nurses are usually the first hospital person the patient sees. Most are warm and welcoming and lovely. Fatima’s … a bit different. She looks a little like Oddjob from Goldfinger. A large lady, ever so slightly menacing, she manages to look expressionless and disapproving at the same time – both of us and of the patients. (I’m sure she’s lovely really.) I explain the faint, the irregular pulse, and as delicately as I can, the S&M thrashing. It’s a bit like being a lawyer, in court defending a client before a judge. Fatima just stares, then writes unwell patient on the triage form.

All human life, as I said.

On the way out a colleague shouts cheerfully:

—Don’t use the coffee machine! One of the NFAs (no fixed abode) was taking the spoons out earlier, licking them and putting them back!

Nice. (Makes a change from drinking the alcohol gel I suppose.)

End of shift and good night.

When the going gets tough – we’re out of here.

We go back to the station – a huge, cavernous building with two sets of double doors that you drive in and out of. Ambulances come in one end and out the other, like sausages. Old and a bit dirty. Occasionally a pigeon flies in and we have to shoo it out. The station tells you a bit about the service. There are pictures on the walls of ambulances parked in formation, back in the 1970s and 80s and 90s. In the days when ambulance crews washed the ambulances, kitted them out, cleaned the station, even sat down and had a meal together. Nowadays, we’re so busy that teams of people do all that for us – we collect our ambulances at the start of the shift and we’re off out and might not see the station again until twelve or thirteen hours later. Though sometimes, on quieter nights, you can open up little cupboard rooms around the station and find old abandoned equipment and stuff in them, decades old. There’s probably a body in there somewhere. Or someone living there. Maybe a patient?

I tell one of the bosses about the shift.

He’s a very tall, thin man, slightly frightening and balding, called Len. Ex-forces, in the job a million years. A man of staring eyes and whispered words, unsmiling. Whatever bit of the forces he was in may not have been the Charm School Corps. He’s retired now. Modern ambulance officers are a little more … cuddly, I suppose. He ponders the jobs a few minutes, then gives his stock response to a lot of things.

—Stupid buggers.

—I felt sorry for them, says Val. Especially the one who’s mentally ill.

Len stares at her.

—What d’you want to feel sorry for him for? He’s a nutter.

I get home about midnight – dog-tired – as Jo’s going to bed. The kids who I left too early to see this morning are long in bed and I won’t see them tonight. I pour myself an industrial-sized whisky. There might be another after that.

Jo looks at me.

—You know you’re drinking too much, don’t you?

This is the life. Just another long, crazy shift. Ours not to reason why, ours just to bitch and moan and wonder how the hell we all ended up here. What’s the Talking Heads song? ‘Once in a Lifetime’?

And you may ask yourself:

How did I get here?

2

Communication (#ud951efb8-327c-55c5-b8d5-6e337b82cb10)

I joined the ambulance service in 2003 because I thought it would give me the sort of job I wanted. Something where you can make a difference. I may have a low boredom threshold. The service is rarely boring.

Up to then I’d had not exactly what you’d call a successful career. I only got to university because my girlfriend dumped me and went off to university herself, so I thought I’d better do the same. But I still didn’t have much of a clue, so I followed my parents into journalism. Which I wasn’t very good at.

I started doing shifts on the diary column of a well-known paper. I was so terrified my first morning I had to drink vodka before I went in to work just so I didn’t shake too much. I was supposed to write fun snippets of news about famous people, but I didn’t know any. The first piece I wrote ended up libelling someone so badly she won undisclosed damages in the High Court. I was told ‘undisclosed’ means at least five figures.

I never went back.

I decided to play it safe and went to work on a boring magazine called Fish Trader, about people who trade in … fish. The only interesting thing about working there was that along the corridor you had other magazines with titles like Disaster Management, which sounded fun.

From there I moved to Scotland, to work on a local paper, which was more like being a proper reporter, although I couldn’t understand most of the accents. It’s difficult to quote people when you haven’t a clue what they said. Good training for talking to people in pain and distress now, though.

Then I found out my mother was dying of cancer, and that changed things.

I left to live with her back in England. She lived alone. I spent a year watching her die in front of my eyes. That was probably good training for the ambulance service too. Just before she died she said the last year of her life had been the best.

I managed to get shift work on national newspapers after that, but never really had the confidence. I could never think of ideas for news stories, and felt frightened of most of the other people in the office. All of them seemed to have gone to Oxford or Cambridge or both. Sometimes I had to take a pill just to go and talk to the news editor or pick up the phone. So I left and painted houses and moved furniture. I don’t miss journalism.

Reporting and ambulance work, asking people questions and trying to make sense of what they tell you, do have similarities. In news reporting, you’re going out to people, trying to understand what’s happened to them, and telling the readers. With ambulance work, you’ve got to find out what’s happened a bit more quickly, then do something about it. Then report to the hospital. Otherwise it’s much the same thing. Sometimes just talking to people is the most important thing.

Sometimes their lives depend on it …

Douglas

Monday morning.

I apologise to any cardiologists, doctors or paramedics reading, but I may have invented a medical procedure. Maybe.

Called to a male, sixties, chest pains.

The symptoms are classic. Crushing central chest pain, radiating into left arm and jaw. Short of breath and dizzy and pale. Needs to go to the loo, sense of doom. Textbook stuff. Douglas is a tall, quite slim gent, alone in the house and very calm and pleasant. But it looks like a heart attack, and he knows it.

After he’s been to the loo, we give him oxygen and aspirin and a spray in the mouth that takes a little of the pain away, then pop him on the carry chair and wheel him out to the ambulance. Once we’ve wired him up to the monitor, there’s little room left for doubt. His ECG has what’s known in the trade as massive ST elevation – another classic sign. At the hospital they’ll do blood tests, but basically, if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck …

The doctors can give drugs that break up the clot, or even stick a tube into his veins to suck the thing out, but at the moment it’s close to killing him.

So off to the hospital we go with lights and sirens flashing. Val’s driving.

On the way in I do my best to reassure him, which isn’t difficult. He seems quite calm and sensible. I can’t imagine that I would be, in his situation. The spray has taken away some of the pain and he can breathe better, and I think he’s gone into crisis mode – he knows exactly what’s going on, and is almost waiting to find out what’s going to happen. (I suppose it’s not much fun having a heart attack, but probably the last thing you’d call it is boring.)