Antony and Cleopatra

COLLEEN McCULLOUGH

Antony and Cleopatra

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This paperback edition 2008

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2007

Copyright © Colleen McCullough 2007

Colleen McCullough asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are

the work of the author’s imagination, and, while

historical characters make appearances in the book,

this is a fictionalised account.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007225804

Ebook edition: September 2008 ISBN: 9780007283712

Version: 2018-06-08

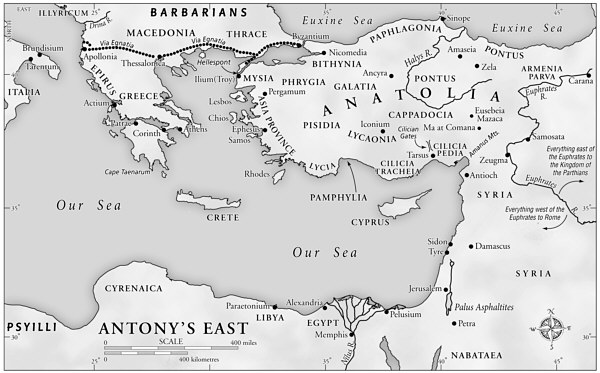

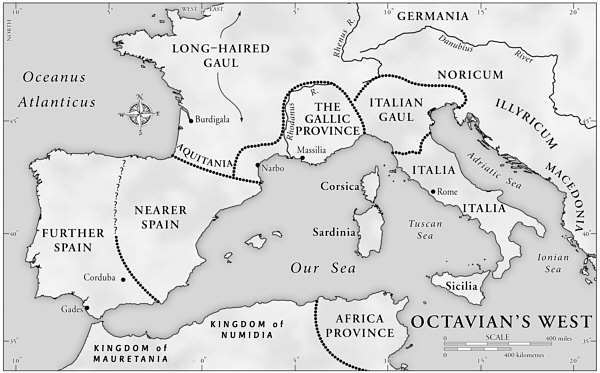

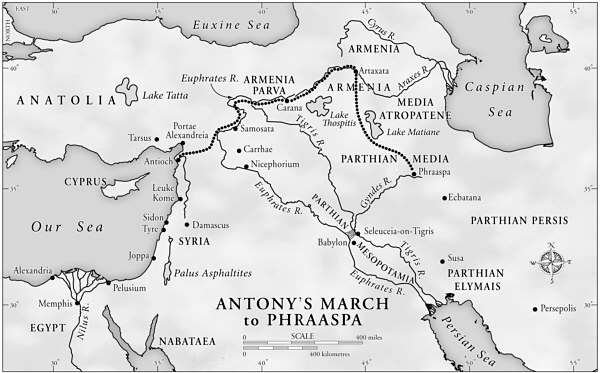

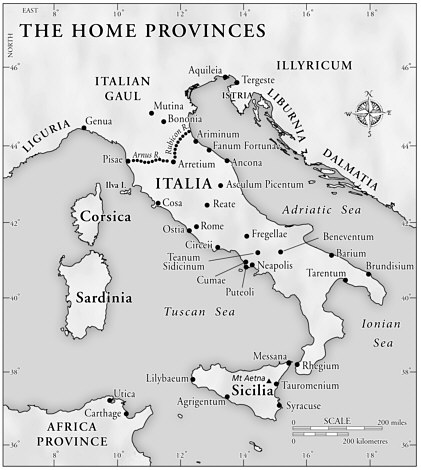

MAPS

For the unsinkable Anthony Cheetham with love and enormous respect

CONTENTS

Title Page Copyright Maps PART I Antony in the East 41–40 B.C. Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five PART II Octavian in the West 41–39 B.C. Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten PART III Victories and Defeats 39–37 B.C. Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen PART IV The Queen of Beasts 36–33 B.C. Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One Chapter Twenty-Two Chapter Twenty-Three Chapter Twenty-Four PART V War 32–30 B.C. Chapter Twenty-Five Chapter Twenty-Six Chapter Twenty-Seven Chapter Twenty-Eight PART VI Metamorphosis 29–27 B.C. Chapter Twenty-Nine Glossary About the Author By the Same Author About the Publisher

PART I

Antony in the East

41–40 B.C.

ONE

Quintus Dellius was not a warlike man, nor a warrior when in battle. Whenever possible he concentrated upon what he did best, namely to advise his superiors so subtly that they came to believe the ideas were genuinely theirs.

So after Philippi, in which conflict he had neither distinguished himself nor displeased his commanders, Dellius decided to attach his meager person to Mark Antony and go east.

It was never possible, Dellius reflected, to choose Rome; it always boiled down to choosing sides in the massive, convulsive struggles between men determined to control – no, be honest, Quintus Dellius! – determined to rule Rome. With the murder of Caesar by Brutus, Cassius and the rest, everyone had assumed that Caesar’s close cousin, Mark Antony, would inherit his name, his fortune, and his literally millions of clients. But what had Caesar done? Made a last will and testament that left everything to his eighteen-year-old great-nephew, Gaius Octavius! He hadn’t even mentioned Antony in that document, a blow from which Antony had never really recovered, so sure had he been that he would step into Caesar’s high red boots. And, typical Antony, he had made no plans to take second place. At first the youth everyone now called Octavian hadn’t worried him; Antony was a man in his prime, a famous general of troops and owner of a large faction in the Senate, whereas Octavian was a sickly adolescent as easy to crush as the carapace of a beetle. Only it hadn’t worked out that way, and Antony hadn’t known how to deal with a crafty, sweet-faced boy with the intellect and wisdom of a seventy-year-old. Most of Rome had assumed that Antony, a notorious spendthrift in desperate need of Caesar’s fortune to pay his debts, had been a part of the conspiracy to eliminate Caesar, and his conduct following the deed had only reinforced that. He made no attempt to punish the assassins; rather, he had virtually given them the full protection of the law. But Octavian, passionately attached to Caesar, had gradually eroded Antony’s authority and forced him to outlaw them. How had he done that? By suborning a good percentage of Antony’s legions to his own cause, winning over the People of Rome, and stealing the thirty thousand talents of Caesar’s war chest so brilliantly that no one, even Antony, had managed to prove that Octavian was the thief. Once Octavian had soldiers and money, he gave Antony no choice but to admit him into power as a full equal. After that, Brutus and Cassius made their own bid for power; uneasy allies, Antony and Octavian had taken their legions to Macedonia and met the forces of Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. A great victory for Antony and Octavian that hadn’t solved the vexed question of who would end in ruling as the First Man in Rome, an uncrowned king paying lip service to the hallowed illusion that Rome was a Republic, governed by an upper house, the Senate, and several Assemblies of the People. Together, the Senate and People of Rome: Senatus Populusque Romanus, SPQR.

Typically – Dellius’s thoughts meandered on – victory at Philippi had found Mark Antony without a viable strategy to put Octavian out of the power equation, for Antony was a force of Nature, lusty, impulsive, hot-tempered and quite lacking foresight. His personal magnetism was great, of that kind which draws men by virtue of the most masculine qualities: courage, an Herculean physique, a well-deserved reputation as a lover of women, and enough brain to make him a formidable orator in the House. His weaknesses tended to be excused, for they were equally masculine: pleasures of the flesh, and heedless generosity.

His answer to the problem of Octavian was to divide the Roman world between them, with a sop thrown to Marcus Lepidus, high priest and owner of a large senatorial faction. Sixty years of on-again, off-again civil war had finally bankrupted Rome, whose people – and the people of Italia – groaned under poor incomes, shortages of wheat for bread, and a growing conviction that the betters who ruled them were as incompetent as they were venal. Unwilling to see his status as a popular hero undermined, Antony resolved that he would take the lion’s share, leave the rotting carcass to that jackal Octavian.

So, after Philippi, the victors had carved up the provinces to suit Antony, not Octavian, who inherited the least enviable parts: Rome, Italia, and the big islands of Sicilia, Sardinia and Corsica, where the wheat was grown to feed the peoples of Italia, long since incapable of feeding themselves. It was a tactic in keeping with Antony’s character, ensuring that the only face Rome and Italia saw would belong to Octavian, while his own glorious deeds elsewhere were assiduously circulated throughout Rome and Italia. Octavian to collect the odium, himself the stout-hearted winner of laurels far from the center of government. As for Lepidus, he had charge of the other wheat province, Africa, a genuine backwater.

Ah, but Marcus Antonius did indeed have the lion’s share! Not only of the provinces, but of the legions. All he lacked was money, which he expected to squeeze out of that perennial golden fowl, the East. Of course he had taken all three of the Gauls for himself; though in the West, they were thoroughly pacified by Caesar, and rich enough to contribute funds for his coming campaigns. His trusted marshals commanded Gaul’s legions, of which there were many; Gaul could live without his presence.

Caesar had been killed within three days of setting out for the East, where he had intended to conquer the fabulously rich and formidable Kingdom of the Parthians, using its plunder to set Rome on her feet again. He had planned to be away for five years, and had planned his campaign with all his legendary genius. So now, with Caesar dead, it would be Marcus Antonius – Mark Antony – who conquered the Parthians and set Rome upon her feet again. Antony had conned Caesar’s plans and decided that they showed all the old boy’s brilliance, but that he himself could improve on them. One of the reasons why he had come to this conclusion lay in the nature of the group of men who went East with him; every last one of them was a crawler, a sucker-up, and knew exactly how to play that biggest of fish, Mark Antony, so susceptible to praise, flattery and the fleshpots.

Unfortunately Quintus Dellius did not yet have Antony’s ear, though his advice would have been equally flattering, balm to Antony’s ego. So, riding down the Via Egnatia on a galled and grumpy pony, his balls bruised and his unsupported legs aching, Quintus Dellius waited his chance, which still hadn’t come when Antony crossed into Asia and stopped in Nicomedia, the capital of his province of Bithynia.

Somehow, every potentate and client-king Rome owned in the East had sensed that the great Marcus Antonius would head for Nicomedia, and had scuttled there in their dozens, commandeering the best inns or setting up camp in style on the city’s outskirts. A beautiful place on its dreamy, placid inlet, a place that most people had forgotten lay very close to dead Caesar’s heart. But, because it had, Nicomedia still looked prosperous, for Caesar had exempted it from taxes, and Brutus and Cassius, hurrying west to Macedonia, had not ventured north enough to rape it the way they had raped a hundred cities from Judaea to Thrace. Thus the pink and purple marble palace in which Antony took up residence was able to offer legates like Dellius a tiny room in which to stow his luggage and the senior among his servants, his freedman Icarus. That done, Dellius sallied forth to see what was going on, and work out how he was going to snaffle a place on a couch close enough to Antony to participate in the Great Man’s conversation during dinner.

Kings aplenty thronged the public halls, ashen-pale, hearts palpitating because they had backed Brutus and Cassius. Even old King Deiotarus of Galatia, senior in age and years of service, had made the effort to come, escorted by the two among his sons whom Dellius presumed were his favorites. Antony’s bosom friend Poplicola had pointed out Deiotarus to him, but after that Poplicola admitted himself at a loss – too many faces, not enough service in the East to recognize them.

Smilingly demure, Dellius moved among the groups in their outlandish apparel, eyes glistening at the size of an emerald or the weight of gold upon a coiffed head. Of course he had good Greek, so Dellius was able to converse with these absolute rulers of places and peoples, his smile growing wider at the thought that, despite the emeralds and the gold, every last one of them was here to pay obsequious homage to Rome, their ultimate ruler. Rome, who had no king, whose senior magistrates wore a simple, purple-bordered white toga and prized the iron ring of some senators over a ton of gold rings; an iron ring meant that a Roman family had been in and out of office for five hundred years. A thought that made poor Dellius automatically hide his gold senatorial ring in a fold of toga; no Dellius had yet reached the consulship, no Dellius had been prominent a hundred years ago, let alone five. Caesar had worn an iron ring, but Antony did not; the Antonii were not quite antique enough. And Caesar’s iron ring had gone to Octavian.

Oh, air, air! He needed fresh air!

The palace was built around a huge peristyle garden that had a fountain at its middle athwart a long, shallow pool. It was fashioned of pure white Parian marble on a fishy theme – mermen, tritons, dolphins – and it was rare in that it had never been painted to imitate real life’s colors. Whoever had sculpted its glorious creatures had been a master. A connoisseur of fine art, Dellius gravitated to the fountain so quickly that he failed to notice that someone had beaten him to it, was sitting in a dejected huddle on its broad rim. As Dellius neared, the fellow lifted his head; no chance to avoid a meeting now.

He was a foreigner, and a noble one, for he wore an expensive robe of Tyrian purple brocade artfully interwoven with gold thread, and upon a head of snakelike, greasy black curls sat a skullcap made of cloth of gold. Dellius had seen enough Easterners to know that the curls were not dirty greasy; Easterners pomaded their locks with perfumed creams. Most of the royal supplicants inside were Greeks whose ancestors had dwelled in the East for centuries, but this man was a genuine Asian local of a kind Dellius recognized because there were many like him living in Rome. Oh, not clad in Tyrian purple and gold! Sober fellows who favored homespun fabrics in dark plain colors. Even so, the look was unmistakable; he who sat on the edge of the fountain was a Jew.

‘May I join you?’ Dellius asked in Greek, his smile charming.

An equally charming smile appeared on the stranger’s jowly face; a perfectly manicured hand flashing with rings gestured. ‘Please do. I am Herod of Judaea.’

‘And I am Quintus Dellius, Roman legate.’

‘I couldn’t bear the crush inside,’ said Herod, thick lips turning down. ‘Faugh! Some of those ingrates haven’t had a bath since their midwives wiped them down with a dirty rag.’

‘You said Herod. No king or prince in front of it?’

‘There should be! My father was Antipater, a prince of Idumaea who stood at the right hand of King Hyrcanus of the Jews. Then the minions of a rival for the throne murdered him. He was too well liked by the Romans, including Caesar. But I dealt with his killer,’ Herod said, voice oozing satisfaction. ‘I watched him die, wallowing in the stinking corpses of shellfish at Tyre.’

‘No death for a Jew,’ said Dellius, who knew that much. He inspected Herod more closely, fascinated by the man’s ugliness. Though their ancestry was poles apart, Herod bore a peculiar likeness to Octavian’s intimate Maecenas – they both resembled frogs. Herod’s protruding eyes, however, were not Maecenas’s blue; they were the stony glassy black of obsidian. ‘As I remember,’ Dellius continued, ‘all of southern Syria declared for Cassius.’

‘Including the Jews. And I personally am beholden to the man, for all that Antonius’s Rome deems him a traitor. He gave me permission to put my father’s murderer to death.’

‘Cassius was a warrior,’ Dellius said pensively. ‘Had Brutus been one too, the result at Philippi might have been different.’

‘The birds twitter that Antonius also was handicapped by an inept partner.’

‘Odd how loudly birds can twitter,’ Dellius answered with a grin. ‘So what brings you to see Marcus Antonius, Herod?’

‘Did you perhaps notice five dowdy sparrows among the flocks of gaudy pheasants inside?’

‘No, I can’t say that I did. Everyone looked like a gaudy pheasant to me.’

‘Oh, they’re there, my five Sanhedrin sparrows! Preserving their exclusivity by standing as far from the rest as they can.’

‘That, in there, means they’re in a corner behind a pillar.’

‘True,’ said Herod, ‘but when Antonius appears, they’ll push to the front, howling and beating their breasts.’

‘You haven’t told me yet why you’re here.’

‘Actually, it’s more that the five sparrows are here. I’m watching them like a hawk. They intend to see the Triumvir Marcus Antonius and put their case to him.’

‘What’s their case?’

‘That I am intriguing against the rightful succession, and that I, a gentile, have managed to draw close enough to King Hyrcanus and his family to be considered as a suitor for Queen Alexandra’s daughter. An abbreviated version, but to hear the unexpurgated one would take years.’

Dellius stared, blinked his shrewd hazel eyes. ‘A gentile? I thought you said you were a Jew.’

‘Not under Mosaic law. My father married Princess Cypros of Nabataea. An Arab. And since Jews count descent in the mother’s line, my father’s children are gentiles.’

‘Then – then what can you accomplish here, Herod?’

‘Everything, if I am let do what must be done. The Jews need a heavy foot on their necks – ask any Roman governor of Syria since Pompeius Magnus made Syria a province. I intend to be King of the Jews, whether they like it or not. And I can do it. If I marry a Hasmonaean princess directly descended from Judas Maccabeus. Our children will be Jewish, and I intend to have many children.’

‘So you’re here to speak in your defence?’ Dellius asked.

‘I am. The deputation from the Sanhedrin will demand that I and all the members of my family be exiled on pain of death. They’re not game to do that without Rome’s permission.’

‘Well, there’s not much in it when it comes to backing Cassius the loser,’ said Dellius cheerily. ‘Antonius will have to choose between two factions that supported the wrong man.’

‘But my father supported Julius Caesar,’ Herod said. ‘What I have to do is convince Marcus Antonius that if I am allowed to live in Judaea and advance my status, I will always stand for Rome. He was in Syria years ago when Gabinius was its governor, so he must be aware how obstreperous the Jews are. But will he remember that my father helped Caesar?’

‘Hmm,’ purred Dellius, squinting at the rainbow sparkles of the water jetting from a dolphin’s mouth. ‘Why should Marcus Antonius remember that, when more recently you were Cassius’s man? As, I gather, was your father before he died.’

‘I am no mean advocate, I can plead my case.’

‘Provided you are permitted the chance.’ Dellius got up and held out his hand, shook Herod’s warmly. ‘I wish you well, Herod of Judaea. If I can help you, I will.’

‘You would find me very grateful.’

‘Rubbish!’ Dellius laughed as he walked away. ‘All your money is on your back.’

Mark Antony had been remarkably sober since marching for the East, but the sixty men in his entourage had expected that Nicomedia would see Antony the Sybarite erupt. An opinion shared by a troupe of musicians and dancers who had hastened from Byzantium at the news of his advent in the neighborhood; from Spain to Babylonia, every member of the League of Dionysiac Entertainers knew the name Marcus Antonius. Then, to general amazement, Antony had dismissed the troupe with a bag of gold and stayed sober, albeit with a sad, wistful expression on his ugly-handsome face.

‘Can’t be done, Poplicola,’ he said to his best friend with a sigh. ‘Did you see how many potentates were lining the road as we came in? Cluttering up the halls the moment the steward opened the doors? All here to steal a march on Rome – and me. Well, I don’t intend to let that happen. I didn’t choose the East as my bailiwick to be diddled out of the goodies the East possesses in such abundance. So I’ll sit dispensing justice in Rome’s name with a clear head and a settled stomach.’ He giggled. ‘Oh, Lucius, do you remember how disgusted Cicero was when I spewed into your toga on the rostra?’ Another giggle, a shrug. ‘Business, Antonius, business!’ he apostrophized himself. ‘They’re hailing me as the new Dionysus, but they’re about to discover that for the time being I’m dour old Saturn.’ The red-brown eyes, too small and close together to please a portrait sculptor, twinkled. ‘The new Dionysus! God of wine and pleasure – I must say I rather like the comparison. The best they did for Caesar was simply God.’

Having known Antony since they were boys, Poplicola didn’t say that he thought God was superior to the God of This or That; his chief job was to keep Antony governing, so he greeted this speech with relief. That was the thing about Antony; he could suddenly cease his carousing – sometimes for months on end – especially when his sense of self-preservation surfaced. As clearly it had now. Alocus he was right; the potentatic invasion meant trouble as well as hard work, therefore it behooved Antony to get to know them individually; learn which rulers should keep their thrones, which lose them to more capable men. In other words, which rulers were best for Rome.

All of which meant that Dellius held out scant hope that he would achieve his goal of moving closer to Antony in Nicomedia. Then Fortuna entered the picture, commencing with Antony’s command that dinner would not be in the afternoon, but later. And as Antony’s gaze roved across the sixty Romans strolling into the dining room, for some obscure reason it lit upon Quintus Dellius. There was something about him that the Great Man liked, though he wasn’t sure what; perhaps a soothing quality that Dellius could smear over even the most unpalatable subjects like a balm.

‘Ho, Dellius!’ he roared. ‘Join Poplicola and me!’

The brothers Decidius Saxa bristled, as did Barbatius and a few others, but no one said a word as the delighted Dellius shed his toga on the floor and sat on the back of the couch that formed the bottom of the U. While a servant gathered up the toga and folded it – a difficult task – another servant removed Dellius’s shoes and washed his feet. He didn’t make the mistake of usurping the locus consularis; Antony would occupy that, with Poplicola in the middle. His was the far end of the couch, socially the least desirable position, but for Dellius – what an elevation! He could feel the eyes boring into him, the minds behind them busy trying to work out what he had done to earn this promotion.

The meal was good, if not quite Roman enough – too much lamb, bland fish, peculiar seasonings, alien sauces. However, there was a pepper slave with his mortar and pestle, and if a Roman diner could snap his fingers for a pinch of freshly ground pepper, anything was edible, even German boiled beef. Samian wine flowed, though well watered; the moment he saw that Antony was drinking it watered, Dellius did the same.

At first he said nothing, but as the main courses were taken out and the sweeties brought in, Antony belched loudly, patted his flat belly and sighed contentedly.

‘So, Dellius, what did you think of the vast array of kings and princes?’ he asked affably.

‘Very strange people, Marcus Antonius, particularly to one who has never been to the East.’

‘Strange? Aye, they’re that, all right! Cunning as sewer rats, more faces than Janus, and daggers so sharp you never feel them slide between your ribs. Odd, that they backed Brutus and Cassius against me.’

‘Not really so odd,’ said Poplicola, who had a sweet tooth and was slurping at a confection of sesame seeds bound with honey. ‘They made the same mistake with Caesar – backed Pompeius Magnus. You campaigned in the West, just like Caesar. They didn’t know your mettle. Brutus was a nonentity, but for them there was a certain magic about Gaius Cassius. He escaped annihilation with Crassus at Carrhae, then governed Syria extremely well at the ripe old age of thirty. Cassius was the stuff of legends.’