По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

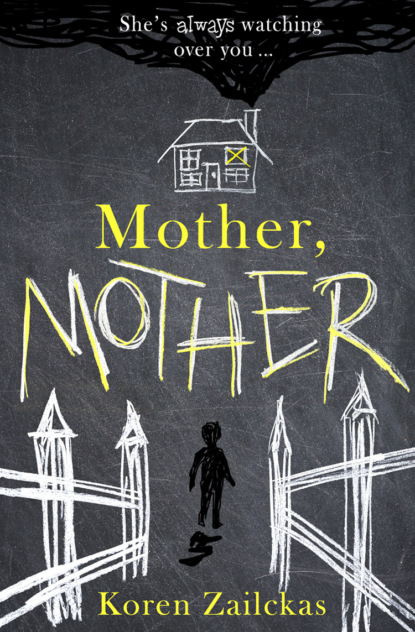

Mother, Mother: Psychological suspense for fans of ROOM

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Yeah. It was scary for a few days. My super-considerate sister moved out without any warning. My parents reported her missing. Turns out she’d only run away. It didn’t take the cops long to find CCTV from the MetroNorth station. The footage showed Rose buying a one-way ticket to Grand Central. She’d been alone, pulling a suitcase. She didn’t look the least bit distressed.”

How was it possible to hate someone straight down to their marrow and still miss them? Violet missed Rose. Desperately. She had never let herself think that before, not one time in all the months since the first responding officer had pulled her aside and pointedly asked, “What do you think happened to your sister?” Even when Josephine started obnoxiously doting on Will and when Douglas—a marginal figure to begin with—fell clean off the pages of the family history.

Sure, there was a time not too long ago when Violet was crying nightly and throwing things at her wall, and she took Rose’s absence as further proof that everyone would discard her in the end. But as the year progressed, Violet had found blotter paper, THC, and transcendence. She’d learned to turn her brain inside out and leave her emotions behind.

But ever since Rose’s letter had arrived, Violet had been feeling like she’d stepped in the same shit again. Her feelings had roared back at high volume. She felt light-headed, off-center. Her shoulders were clenched so tight it hurt to turn her head.

Edie was wearing a look she’d probably borrowed from one of the many shrinks she’d seen over the years. “Was it some kind of cry for attention? You think your sister is BPD?”

“I don’t know what that is.”

“Sorry. Borderline personality disordered. It’s like, an I-love-you-I-hate-you-Don’t-leave-me kinda thing. Emotional roller-coaster shit. Do you think she ran away hoping you all would come hunting her down?”

“Maybe. When we were kids, Rose’s favorite game was hide-and-seek,” Violet said. “She loved hiding at the bottom of the laundry basket, knowing everyone was pulling their hair out trying to find her.”

After lunch Violet borrowed Edie’s phone card. Clutching the greasy yellow receiver, her back to the booth’s closed accordion door, Violet was faced with a first-world problem. She could not remember her best friend’s phone number, which she’d always dialed from the saved entry on her cell phone.

She had three misdials.

She thought for a second and admired the graffiti that still showed through a janitor’s efforts to scrub it off (Is it solipsistic in here, or is it just me?). Then it occurred to her to call 411. Thankfully, Imogene’s parents had a landline.

Two conflicting voices said hello. The frazzled one belonged to Imogene’s mother. The kind of endearingly monotone one was Finch. “I got it, Mom,” he said.

Violet felt as though her tongue had been cut out. “Finch,” she said. Violet’s desperation—she was dying to talk to Imogene—gave her voice a breathy, stalkerette quality.

“Yeah. Is that Violet?”

For the past few months, she’d been trying to put the way she felt about Finch out of her mind. She wouldn’t allow herself to call it a crush. Crushes weren’t a precursor to love, they were a precursor to having your heart chewed up like Shark Week.

“Yeah, it’s me,” Violet said. “Listen, is Imogene there?”

“She’s in the shower. What’s up? Where have you been?”

“Is there any way you could get her? I don’t really know when I’ll be able to call again.”

“Man, Hurst. Are you in the clink or something? Is this your one phone call? Do you need me to call a lawyer for you?”

“I’m not in jail. Just get Imogene, okay? I’m calling on a phone card and I don’t know how much money’s on it.”

After Violet spent a few more minutes perusing the phone booth graffiti, Imogene finally picked up.

“Violet? Are you okay? Finch said you got busted for those seeds. That’s outrageous! They’re legal! For fuck’s sake, we bought them in the gardening section of Gordon’s Fairtrade Farm!”

“I didn’t get arrested. It’s a long story. My mom’s lying about me, I think. Saying I’m abusive to Will. My dad brought me to Fallkill.”

“Wait. What? The mental hospital?! What are you doing there? Do you need us to come get you?”

“You can come visit me. I can’t leave until they say it’s okay.”

“Which ‘they’? The doctors or your parents?”

“The doctors.”

“How is she saying you abused Will?”

“I don’t know. Something happened to his hand. A knife or something. I’m afraid I might be in serious trouble. My mom is trying to decide whether she’s going to press charges.”

“You’re fucking kidding, right? This is serious, Violet. You have to get the fuck out of there. My parents will get you out of there. My mom’s right here.”

“No. Imogene, don’t trouble your mom with this. She’s dealing with enough—”

“Violet? Are you all right?”

Violet thought of magnanimous, huggy Beryl Field as the mother she always wished she had. It had been Beryl who’d taught Violet how to parallel park; who explained to her how to put on eyeliner (“Tilt your head back and close your eye about halfway. Think Marilyn Monroe”). On the night of the spring chorale concert, Beryl had gently suggested Violet take off the reinforced-toe pantyhose Josephine had earlier insisted she wear. (“There! That’s better, don’t you think?” Beryl had said, once the hose were balled in Violet’s pocket. “You looked beautiful before, too. But now, there’s nothing detracting from your pretty peep-toe espadrilles.”) Beryl asked the open-ended questions that Josephine didn’t: where Violet wanted to travel, what qualities Violet found attractive in boys, how she felt about applying for college. Naturally, Josephine thought Beryl was spineless and overindulgent; she liked to poke fun at the way Beryl was raising Imogene like she was a “precious little snowflake” when, in her estimation, what Imogene really needed was a mom with the courage and conviction to “rip the piercings out of her face.”

“I’m okay,” Violet said, fighting back tears.

“Imogene says you’re at Fallkill Psych? What happened, honey?”

Violet couldn’t help registering the hoarse, tired tones in Beryl’s voice. She sounded so unlike the vivacious woman who used to find time to make giant abstract sculptures out of PVC pipes and teach a hula-hoop dance class at the Stone Ridge Community Center.

Violet wanted to ask for help, but she wasn’t yet ready to fully fight her mother’s accusations. She needed more information. She needed time to build her defense case. Whatever had happened to Will, it was Violet’s word against Josephine’s, at least or until she was clear on whether Rose had really been there.

The only words she managed to get out were the understatement of the century: “Nothing happened. I had a fight with my mom and then a panic attack. Or maybe it was the other way around.”

Violet had a sudden picture—a flip book, really—of her mom’s face that night in the kitchen: She saw her mother’s eyes shrink, then widen, then narrow as though she were taking aim. She had a flashback of Josephine’s mouth: first contracting nervously, then opening in a scream of horror, then snarling, her upper lip curling past her eyeteeth. What the hell had Violet said that had propelled her mother’s face—which was usually restricted to sadistic smirks and phony smiles—through such a range of expression?

It still didn’t make sense, the way Violet’s freak-out had incited her mom to have one of her own. Hanging up with Beryl, Violet couldn’t shake Josephine’s good-bye face as she left for the hospital. Her mother’s eyes had held Violet with a looks-could-kill glare. It was a face that carried a vindictive warning. A face that told Violet, Just you wait …

WILLIAM HURST (#ulink_a699efea-4f3f-5c9c-b60f-8fd4f7eb13e5)

“CAN I GET you a Coke?” Douglas asked without looking at Will directly. They were at his office, and he was powering up one of three desktop computers, the login screen prompting him for a password.

Will flinched, then tried to cover his shock. Josephine had always forbidden him soda, and as a result, he’d never developed a taste for it. Everything about Coca-Cola—the smell, the excrement color, the carbonated hiss—made vomit rise in Will’s throat.

“No, thanks,” Will said. “I’m not thirsty.”

Will tried to peer over the desk and track his dad’s fingers as he typed his password. But Douglas was fast. Too fast. In less than a second, he was logged in. The striped IBM logo glowed bright on his monitors.

Will couldn’t help noticing that his dad was different at work. He seemed to be witnessing a complete personality transplant. Before, Will had worried that his father had a parallel life, but the reality was something even more disturbing: his father seemed to have a parallel identity.

The Douglas of Old Stone Way—the evasive guy who had spent all day Sunday glumly going through the motions of church and an IHOP breakfast until he could slip away to the “gym” for close to five hours—was gone. He’d been replaced by the Douglas Hurst of IBM, the kind of chummy blowhard who made people flash squeamish smiles and avert their eyes. He wasn’t confident, exactly, but he had a fine-tuned schtick, composed of business-management-speak and comedic timing.

Will briefly wondered which persona was real, and decided on neither. For a moment, he tried to look at his father from an outsider’s perspective—to see him as Douglas instead of Dad—but all he saw was an aging nerd with thick graying hair and his work shirt buttoned too high on his Adam’s apple. Will didn’t have the first inkling who his father was beyond the surface of his faintly smudged glasses.

Maybe Douglas felt shy and awkward in Will’s presence too. He started rambling abruptly, out of nowhere. “Years ago, we had this PA who never liked to wear the same thing twice … She was obsessive about it. So you know what I did? I built her a program that would help her track her outfits. She’d just input whatever she wanted to wear—polka-dot blouse with a tan blazer, you name it—and the computer would go ballistic and tell her she’d worn the same thing back on the fifth of December.” Douglas laughed and took a slug from his travel mug. “Will, don’t ever let anyone tell you that tech geeks don’t know a thing about women. We’re not all social pariah types. Well … with the exception of Don, here, of course.”

Don, the co-worker who’d been leaning in the doorway, laughed a little too heartily and walked away clutching his chest as though he’d been shot.