По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

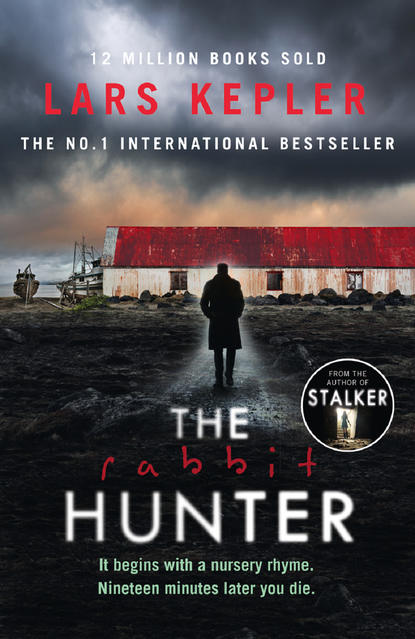

The Rabbit Hunter

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Rabbit Hunter is walking restlessly around the large shipping container in the crooked glare of the fluorescent ceiling light.

He stops in front of a few open crates and a large petrol can. He presses his fingers to his left temple and tries to calm his breathing.

He looks at his phone.

No messages.

As he walks back to his equipment he steps on a laminated map of Djursholm lying on the floor.

He’s put his pistols, knives and rifles in a pile on a battered desk. Some of the weapons are dirty and worn, while others are still in their original packaging.

There’s a pile of rusty tools and old mason jars full of springs and firing pins, extra cartridges, rolls of black bin bags, duct-tape, bags of zip ties, axes and a broad-bladed Emerson knife, its tip honed as sharp as an arrowhead.

He’s stacked boxes containing different types of ammunition against the wall. On top of three of them are photographs of three people.

A lot of the boxes are still closed, but the lid has been torn off one box of 5.56x45mm ammunition, and there are bloody fingerprints on another.

The Rabbit Hunter puts a box of 9mm pistol bullets in a crumpled plastic bag. He examines a short-handled axe and adds it to the bag, then drops the whole thing on the floor with a loud clang.

He reaches out his hand and picks up one of the small photographs. He moves it to the edge of one of the container’s metal ribs, but it falls off.

He puts it back carefully and looks at the face with a smile: the cheery set of the mouth, the unruly hair. He leans forward and looks into the man’s eyes, and decides that he’s going to cut his legs off and watch him crawl like a snail through his own blood.

And he’ll watch the man’s son’s desperate attempts to tie tourniquets around his father’s legs in an effort to save his life, and maybe he’ll let him stem the flow of blood before going over and slicing his stomach open.

The photograph falls again and sails down amongst the weapons.

He lets out a roar and overturns the entire desk, sending pistols, knives and ammunition clattering across the floor.

The glass jars shatter in a cascade of splinters and spare parts.

The Rabbit Hunter leans against the wall, gasping for breath. He remembers the old industrial area that used to be between the highway and the sewage plant. The printing works and warehouses had burned down, and beneath the foundations of an old cottage was a vast rabbit warren.

The first time he checked the trap, there were ten small rabbits in the snares, all exhausted but still alive when he skinned them.

He regains control of himself. He’s calm and focused again. He knows he can’t give in to his rage, can’t show its hideous face, not even when he’s alone.

It’s time to go.

He licks his lips, then picks a knife up off the floor, along with two pistols, a Springfield Operator and a grimy Glock 19. He adds another carton of ammunition and four extra magazines to the plastic bag.

The Rabbit Hunter goes out into the cool night air. He closes the door of the container, pulls the bar across it and fastens the padlock, then walks to the car through the tall weeds. When he opens the boot a cloud of flies emerges. He tosses the bag of weapons in beside the bin-bag of rotting flesh, closes the boot and turns towards the forest.

He looks at the tall trees, conjures up the face in the photograph, and tries to force the rhyme out of his head.

18 (#ulink_24bb7eea-4790-5a81-974e-160f0f1f5155)

In the Salvation Army’s offices at 69 Östermalms Street, a private lunch meeting is underway. Twelve people have made one long table out of three smaller ones, and are now sitting so close that they can see the tiredness and sadness in each other’s faces. The daylight shines in on the pale wooden furniture and the tapestry of the apostles fishing.

At one end sits Rex Müller, in his tailored jacket and black leather trousers. He’s fifty-two years old, still good-looking despite his frown and the swollen bags under his eyes.

Everyone looks at him as he puts his coffee cup back down on the saucer and runs a hand through his hair.

‘My name is Rex, and I usually don’t say anything, I just sit and listen,’ he begins, then gives an awkward little smile. ‘I don’t really know what you want me to say.’

‘Tell us why you’re here,’ says a woman with sad wrinkles around her mouth.

‘I’m a pretty good chef,’ he goes on, and clears his throat. ‘And in my line of work you need to know about wine, beer, fortified wine, spirits, liqueurs and so on … I’m not an alcoholic. I maybe drink a little too much. I do stupid things sometimes, even though you shouldn’t believe everything the papers say.’

He pauses and peers at them with a smile, but they just wait for him to go on.

‘I’m here because my employer insisted, otherwise I’ll lose my job … and I like my job.’

Rex had been hoping for laughter, but they’re all looking at him in silence.

‘I have a son. He’s practically grown up now, in his last year at high school … And one of the things I probably ought to regret about my life is not being a good dad. I haven’t been a dad at all. I’ve been there for birthdays and so on, but … I didn’t really want children, I wasn’t mature enough to …’

His voice cracks in the middle of the sentence, and to his surprise he feels tears welling up in his eyes.

‘OK, I’m an idiot, you might have realised that already,’ he says quietly, then takes a deep breath. ‘It’s like this … My ex, she’s wonderful, there aren’t many people who can say that about their ex, but Veronica is great … And now she’s been hand-picked to launch a big project about free healthcare in Sierra Leone, but she’s thinking of turning it down.’

Rex smiles wryly at the others.

‘She’s perfect for the job … so I told her I was trying to stay sober these days, and that Sammy can live with me when she’s away. Since I’ve been coming to these meetings she believes I’ve started to show more responsibility … and now she’s actually going on her first trip to Freetown.’

He runs his fingers through his messy black hair and leans forward.

‘Sammy’s had a pretty tough time. It’s probably my fault, I don’t know, his life is very different to mine … I’m not for a minute thinking I can repair our relationship, but I am actually looking forward to getting to know him a little better.’

‘Thanks for sharing,’ one of the women says quietly.

Rex Müller has spent the past two years as the resident chef on a popular morning programme on TV4. He’s won silver in the Bocuse d’Or contest, has worked with Magnus Nilsson at Fäviken Magasinet, has published three cookbooks, and last autumn he signed a lucrative contract with the Grupp F12 restaurant company, making him head chef at Smak.

After three hours in the new restaurant he hands things over to Eliza, the sous chef, changes into a blue shirt and suit, and heads over to the inauguration of a new hotel at Hötorget. He gets photographed with Avicii, then takes a taxi out to Dalarö to meet his associates.

David Jordan Andersen – or DJ, as everyone calls him – is thirty-three years old, and set up the production and branded content company that bought the rights to Rex’s cooking. In three years he has taken Rex from one of the country’s foremost chefs to genuine celebrity status.

Now Rex sweeps into the restaurant of the Dalarö Strand Hotel, shakes DJ’s hand and sits down across from him.

‘I thought Lyra was thinking of coming?’ Rex says.

‘She’s meeting her art school friends.’

DJ resembles a modern-day Viking with his full blond beard and blue eyes.

‘Did Lyra think I was difficult last time?’ Rex asks with a frown.

‘You were difficult last time,’ DJ replies frankly. ‘You don’t have to give the cook a lecture every time you go to a restaurant.’