По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

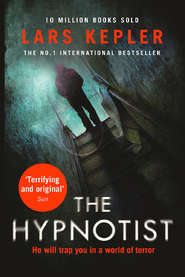

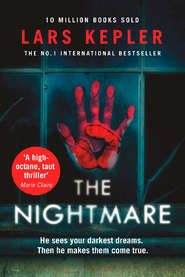

Joona Linna Crime Series Books 1 and 2: The Hypnotist, The Nightmare

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Yes,” says Kennet. “I realise you’ve checked it out. I’ve had a look at the report.”

The other person continues talking. Simone closes her eyes and listens to the hum of the police radio, which becomes part of the muted bumblebee buzz of the voice on the phone.

“But you haven’t measured the house?” she hears her father ask. “No, of course not …”

She opens her eyes and suddenly feels a brief adrenaline rush chase away the tiredness.

“Yes, that would be good … Can you send the plans over here by messenger?” says Kennet. “And any planning applications … Yes, the same address … Thanks a lot.” He ends the call.

“Could Benjamin really be in that house? Could he, Dad?”

“That’s what we’re going to find out.”

“Well, come on then,” she says impatiently.

“Charley’s sending the plans over.”

“Plans? I don’t give a shit about the plans. What are you waiting for? We need to get over there. I can smash down every little—”

“That’s not a good idea. I mean, it’s urgent, but I don’t think we’ll gain any time by going over there and starting to knock down walls.”

“But we have to do something.”

“That house has been crawling with police for the past few days,” he explains. “If there was anything obvious they would have found it, even if they weren’t looking for Benjamin.”

“But—”

“I need to look at the plans to see where it might be possible to build a secret room, get some measurements so I can compare them with the actual measurements when we’re in the house.”

“But what if there is no room? Then where can he be?”

“The Ek family shared a summer cottage outside Bollnäs with the father’s brothers. I have a friend there who promised to drive over. He knows the area very well. It’s in the older part of a development.” Kennet looks at his watch and dials a number. “Svante? Kennet here, I was just wondering—”

“I’m there now,” his friend says.

“Where?”

“Inside the house,” says Svante.

“But you were only supposed to take a look.”

“The new owners let me in; they’re called Sjölin.” Someone says something in the background. “Sorry, Sjödin.” He corrects himself. “They’ve owned the house for over a year.”

“I see. Well, thanks for your help.” Kennet ends the call. A deep furrow appears in his forehead.

“What about the cottage where his sister was?” asks Simone.

“We’ve had people there several times. But you and I could drive out and take a look anyway.”

They fall silent, their expressions thoughtful, introverted. The letter box rattles; the morning paper is pushed through and thuds onto the hall floor. Neither of them moves. They hear the rattle of more letter boxes on the next floor down; then the outside door opens.

Kennet suddenly turns up the volume of the police radio. A call has gone out. Someone answers, demanding information. In the brief exchange, Simone picks up something about a woman hearing screams from a neighbouring apartment. A car is dispatched. In the background, someone laughs and launches into a long explanation about why his younger brother still lives at home and has his sandwiches made for him every morning. Kennet turns the volume down again.

“I’ll make some more coffee,” says Simone.

From his khaki bag, Kennet removes a pocket atlas of Greater Stockholm. He takes the candlesticks from the table and places them in the window before opening it. Simone stands behind him, contemplating the tangled network of roads, rail, and bus links crisscrossing one another in shades of red, blue, green, and yellow. Forests and geometric suburban systems.

Kennet’s finger follows a yellow road south of Stockholm, passing Älvsjö, Huddinge, Tullinge, and down to Tumba. Together they stare at Tumba and Salem. It is a pale map showing an old and once-isolated community that was saved from decay and irrelevance when a commuter train station was built there, creating a new town centre. The detailed map indicates a post-war boom: new construction of high-rise apartments and shops, a church, a bank, and a state-owned off licence has brought suburban convenience and comfort to the old town. Terrace houses and residential areas branch out from a central core. There are a few fields the colour of yellow straw just north of the community; after a few miles these give way to forests and lakes.

Kennet traces the street names and circles a point among the narrow rectangles that lie parallel to one another like ribs.

“Where the hell is that messenger?” he mutters.

Simone pours two mugs of coffee and pushes the box of sugar cubes over to her father. “How did he get in?” she asks.

“Josef Ek? Well, presumably he had a key, or else somebody opened the door to him.”

“Couldn’t he have broken in?”

“Not with this kind of lock, it’s too difficult; much easier to break down the door.”

She nods, trying to think methodically. “Should we take a look at Benjamin’s computer?”

“We should have done that before. I did think about it, but then I forgot. I must be getting tired,” says Kennet.

Simone notices that he’s looking old. She’s never thought about his age before. He looks at her, his mouth sad. “Try and get some sleep while I check the computer,” she says.

“Forget it.”

When Simone walks into Benjamin’s room with Kennet, it feels desolate. Benjamin seems so terrifyingly far away. Another wave of nausea sweeps over her. She swallows and swallows, wanting to return to the lighted kitchen where the police radio murmurs and hums. Death waits here in the darkness, a final emptiness from which she will never recover.

She switches on the computer and the screen flashes; the lights come on with a click, the fans begin to whir, and the hard drive issues its command. When she hears the welcome melody from the operating system, it feels as if something of Benjamin has come back.

Father and daughter each pull out a chair and sit down. Simone clicks on the miniature picture of Benjamin’s face to log in.

“We need to take this slowly and methodically,” says Kennet. “Let’s start with his e-mails.” But the computer demands a password. “Try his name,” says Kennet. She types BENJAMIN, but is denied access. She tries AIDA, turns the names around, puts them together. She tries BARK, BENJAMIN BARK, blushes as she tries SIMONE and SIXAN, tries ERIK, tries the names of the artists Benjamin listens to: SEXSMITH, ANE BRUN, RORY GALLAGHER, JOHN LENNON, TOWNES VAN ZANDT, BOB DYLAN.

“This is no good,” says Kennet. “We need to get someone over here who can hack in for us.”

She tries a few film titles and directors that Benjamin talks about, but she gives up after a while; it’s impossible.

“We should have gotten the plans by now,” says Kennet. “I’ll call Charley and see what’s happening.”

They both jump at the knock on the front door. Simone stays at the computer and watches, her heart pounding, as Kennet goes into the hallway and turns the latch.

48

sunday, december 13 (feast of st lucia): morning