По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

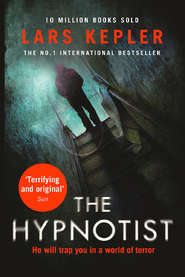

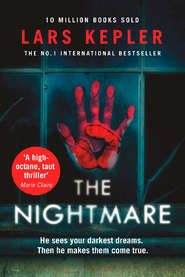

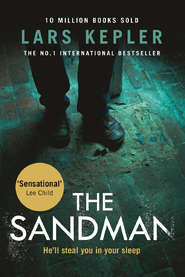

Joona Linna Crime Series Books 1-3: The Hypnotist, The Nightmare, The Fire Witness

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Inside the house,” says Svante.

“But you were only supposed to take a look.”

“The new owners let me in; they’re called Sjölin.” Someone says something in the background. “Sorry, Sjödin.” He corrects himself. “They’ve owned the house for over a year.”

“I see. Well, thanks for your help.” Kennet ends the call. A deep furrow appears in his forehead.

“What about the cottage where his sister was?” asks Simone.

“We’ve had people there several times. But you and I could drive out and take a look anyway.”

They fall silent, their expressions thoughtful, introverted. The letter box rattles; the morning paper is pushed through and thuds onto the hall floor. Neither of them moves. They hear the rattle of more letter boxes on the next floor down; then the outside door opens.

Kennet suddenly turns up the volume of the police radio. A call has gone out. Someone answers, demanding information. In the brief exchange, Simone picks up something about a woman hearing screams from a neighbouring apartment. A car is dispatched. In the background, someone laughs and launches into a long explanation about why his younger brother still lives at home and has his sandwiches made for him every morning. Kennet turns the volume down again.

“I’ll make some more coffee,” says Simone.

From his khaki bag, Kennet removes a pocket atlas of Greater Stockholm. He takes the candlesticks from the table and places them in the window before opening it. Simone stands behind him, contemplating the tangled network of roads, rail, and bus links crisscrossing one another in shades of red, blue, green, and yellow. Forests and geometric suburban systems.

Kennet’s finger follows a yellow road south of Stockholm, passing Älvsjö, Huddinge, Tullinge, and down to Tumba. Together they stare at Tumba and Salem. It is a pale map showing an old and once-isolated community that was saved from decay and irrelevance when a commuter train station was built there, creating a new town centre. The detailed map indicates a post-war boom: new construction of high-rise apartments and shops, a church, a bank, and a state-owned off licence has brought suburban convenience and comfort to the old town. Terrace houses and residential areas branch out from a central core. There are a few fields the colour of yellow straw just north of the community; after a few miles these give way to forests and lakes.

Kennet traces the street names and circles a point among the narrow rectangles that lie parallel to one another like ribs.

“Where the hell is that messenger?” he mutters.

Simone pours two mugs of coffee and pushes the box of sugar cubes over to her father. “How did he get in?” she asks.

“Josef Ek? Well, presumably he had a key, or else somebody opened the door to him.”

“Couldn’t he have broken in?”

“Not with this kind of lock, it’s too difficult; much easier to break down the door.”

She nods, trying to think methodically. “Should we take a look at Benjamin’s computer?”

“We should have done that before. I did think about it, but then I forgot. I must be getting tired,” says Kennet.

Simone notices that he’s looking old. She’s never thought about his age before. He looks at her, his mouth sad. “Try and get some sleep while I check the computer,” she says.

“Forget it.”

When Simone walks into Benjamin’s room with Kennet, it feels desolate. Benjamin seems so terrifyingly far away. Another wave of nausea sweeps over her. She swallows and swallows, wanting to return to the lighted kitchen where the police radio murmurs and hums. Death waits here in the darkness, a final emptiness from which she will never recover.

She switches on the computer and the screen flashes; the lights come on with a click, the fans begin to whir, and the hard drive issues its command. When she hears the welcome melody from the operating system, it feels as if something of Benjamin has come back.

Father and daughter each pull out a chair and sit down. Simone clicks on the miniature picture of Benjamin’s face to log in.

“We need to take this slowly and methodically,” says Kennet. “Let’s start with his e-mails.” But the computer demands a password. “Try his name,” says Kennet. She types BENJAMIN, but is denied access. She tries AIDA, turns the names around, puts them together. She tries BARK, BENJAMIN BARK, blushes as she tries SIMONE and SIXAN, tries ERIK, tries the names of the artists Benjamin listens to: SEXSMITH, ANE BRUN, RORY GALLAGHER, JOHN LENNON, TOWNES VAN ZANDT, BOB DYLAN.

“This is no good,” says Kennet. “We need to get someone over here who can hack in for us.”

She tries a few film titles and directors that Benjamin talks about, but she gives up after a while; it’s impossible.

“We should have gotten the plans by now,” says Kennet. “I’ll call Charley and see what’s happening.”

They both jump at the knock on the front door. Simone stays at the computer and watches, her heart pounding, as Kennet goes into the hallway and turns the latch.

48

sunday, december 13 (feast of st lucia): morning

The December sky is as pale as sand; the temperature is a few degrees above zero as Kennet and Simone drive into the part of Tumba where Josef Ek was born and grew up and where, at the age of fifteen, he slaughtered his family. The house looks just like the other houses on the street: neatly kept, unremarkable. If not for the black-and-yellow police tape, nobody would suspect that a week ago this house was the scene of two of the country’s most long-drawn-out and merciless murders.

A bicycle with training wheels sits near a sandpit at the front of the house. One end of the police tape has come loose and blown about, finally getting stuck in the letter box opposite. Kennet doesn’t stop but drives past slowly. Simone peers in the windows. The curtains are drawn and the place looks completely deserted. The whole row of houses seems to have been abandoned. Could she live on a street where something like this had happened? She shudders. They roll to the end of the cul-de-sac, swing around, and are approaching the scene of the crime once more when Simone’s phone suddenly rings.

She answers quickly—“Hello?”—and listens for a moment. “Has something happened?”

Kennet stops the car, turns off the engine, and gets out. From the capacious boot he takes a crowbar, a tape measure, and a torch. He hears Simone say that she has to go before he slams the boot shut.

“What do you think?” Simone yells into the phone.

Kennet can hear her through the car windows and carefully gauges her distressed expression as she gets out of the passenger seat with the house plans in her hand. Without speaking they walk together towards the white gate in the low fence. It squeaks slightly as it opens. Kennet tips a key out of an envelope, continues to the door, and unlocks it. Before he goes in he turns back to look at Simone and he nods briefly, noting the resolute look on her face.

As soon as they walk into the hallway they are hit by the sickening smell of rancid blood. For a brief moment Simone feels panic rising in her chest: the stench is rotten, sweet, not unlike excrement. She glances at Kennet. He doesn’t seem troubled, just focused, his movements carefully considered. They go past the living room. From the corner of her eye Simone has an impression of the bloodstained walls and soapstone fireplace, the overwhelming chaos, the fear lifting from the floor.

They can hear a strange creaking noise from somewhere inside the house. Kennet stops dead, calmly takes out his former service pistol, removes the safety catch, and checks that it is loaded.

They hear something else: a swaying, heavy, dragging noise. It doesn’t sound like footsteps. It sounds more like someone slowly crawling.

49

sunday, december 13 (feast of st lucia): morning

Erik wakes in the narrow bed in his office at the hospital. It’s the middle of the night. Glancing at the clock on his mobile, he sees it’s almost three. He takes another pill and lies shivering under the covers until the tingling spreads through his body and the darkness comes sweeping back in.

When he wakes up several hours later, he has a splitting headache. He takes a painkiller, goes over to the window, and lets his eyes roam over the gloomy façade with its hundreds of windows. The sky is white, but every window is still in darkness.

He puts his phone down on the desk and gets undressed. The small shower stall smells of disinfectant. The warm water flows over his head and the back of his neck, and thunders against the Plexiglas.

When he has dried himself he wipes off the mirror, moistens his face, and covers it with shaving foam. He is thinking about the fact that Simone said the front door of the apartment had been open the night before Josef Ek ran away from the hospital. She was awake, and she went and closed it. But it couldn’t have been Josef Ek on that occasion. Erik tries to understand what happened during the night, but there are too many unanswered questions. How did Josef get in? Did he simply knock on the door until Benjamin woke up and opened it?

Erik imagines the two boys standing there regarding each other in the faint light from the stairwell. Benjamin is barefoot, his hair on end; he is wearing his childish pyjamas and blinking with tired eyes at the taller boy. You could say they are not unlike each other, except that Josef has murdered his parents and his younger sister, has just killed a nurse at the hospital with a scalpel, and seriously injured a man at the Northern Cemetery.

“No,” Erik says to himself. “I don’t believe this. It doesn’t make sense.”

Who would be able to get in, who would Benjamin open the door to, who would Simone or Benjamin trust with a key? Perhaps Benjamin was expecting a nocturnal visit from Aida. Not unheard of; Erik has to think of everything. Perhaps Josef was working with someone who helped him with the door, perhaps Josef had actually intended to come on the first night but couldn’t manage to get away, and his partner had left the door open for him in accordance with their plans.

Erik finishes shaving and brushes his teeth, picks up the phone, checks the time, and calls Joona.