По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

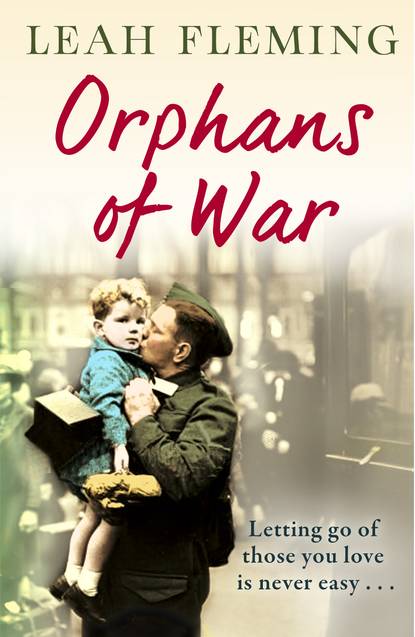

Orphans of War

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Not now you don’t, love. All that timber and thatch, gone up like tinder. I’m sorry. We’re digging them out across the road. It’s not safe if the petrol tank goes up…The airfield got it bad tonight,’ said the blackened-faced fireman, trying to be kind, but she didn’t want to hear his words.

Another man in uniform was talking to a woman in a uniform.

‘Two survivors for you, Mavis,’ he said, pointing them out. ‘Take them for some tea.’

‘We’ve had our supper, thank you,’ Maddy said. ‘What about my dog, Bertie? You’ve got to look for him too.’

‘Bertie’ll be fine, love. Let the men get on with their jobs. I don’t think he went in the cellar. He’ll be hiding until it’s safe. We can look for him later,’ Ivy offered, putting her arm round her, but Maddy shook it off. She must find Bertie.

Maddy could see Mr Finlay from the garage across the road, standing in a daze with a shawl around his shoulders and the children from the house up the lane, clutching teddy bears and whimpering. But when she turned to see if anyone was coming out of the pub she saw only smoke and firemen and burning wood. It was a terrible smell and she started to shake.

Someone led them away but her legs were all wobbly. This was all a bad dream…but why could she feel the heat searing her face and still she didn’t wake up?

Later they stood wrapped in blankets sipping tea, feeling sick after inhaling the choking smoke, as the sky turned orange. The fire brigade did their best to quell the flames but it was all too late and the whole town seemed to be on fire.

Maddy would never forget the smell of burning timbers and the flashes and explosions as the bottles cracked and kegs exploded as the poor pub went up in smoke. Nothing would be safe in the world after this. She was shaking, too shocked to take in the enormity of what was happening as they were led shivering, covered in black dust, to the Miner’s Arms, to be given a makeshift bed in the bar, along with all the other victims of the blitz.

They drank sweet tea until they were choking with the stuff. Only then did someone prise the newspaper package out of Maddy’s hand.

On that September night, the whole area was brought to rubble by stray bombs offloaded on a raid. Nothing would ever be the same again. Suddenly Maddy felt all floaty and strange as if she was watching things from on top of the church tower.

In the days that followed the blitz she roamed over the ruins and the back roads of Chadley, calling out for Bertie. How could her poor old dog try to dodge fire, run for shelter, scavenge around or fight off mangy waifs and strays? She called and called until she was hoarse but he never appeared and she knew Bertie was gone.

Then it was as if her throat closed over and no sound could come out. Miss Connaught came and offered her place back in the school–but with no money to her name, she bowed her head and refused to budge from her makeshift billet in the Miner’s.

Ivy took her home to the cottage down the street where she had to share a bed with Ivy’s little sister, Carol. All Maddy wanted to do was sit by the scorched apple tree and wait for Bertie, but the sight of the ruined timbers was so terrible she couldn’t bear to stay for more than a few minutes. If she could find him then she would have someone in the world to hug for comfort while the authorities decided what to do with her.

Telegrams were cabled to the Bellaires in Durban. Maddy had to sign forms in her best joined-up handwriting to register for immediate housing and papers.

The funeral arrangements were taken out of Maddy’s hands by the vicar and his wife. He suggested a joint service for all the bomb victims in Chadley parish church. She overheard Ivy whispering that the coffins would be filled with sand because no trace of Granny and George had been found. The thought of them burned up gave her nightmares and she screamed and woke up all the Sangsters.

Ration books were granted, and coupons for mourning clothes, but everything just floated past her as if in some silent dream. She shed no tears at the service. Maddy stood up straight and looked ahead. They weren’t in those boxes by the chancel steps. There were other boxes, and two little ones: the children from the garage, who had died in the explosion. The family clung together, sobbing.

Why weren’t Mummy and Daddy here? Why were they off out of it all? All Maddy felt was a burning heat where her heart was. Everything was destroyed–her home, her family–and just the comfort of strangers for company. Where would she go? To an orphanage or back to St Hilda’s?

Then a telegram appeared from an address in Yorkshire.

YOUR FATHER HAS INSTRUCTED YOU TO COME NORTH. WILL MEET YOU ON LEEDS STATION. WEDNESDAY. PRUNELLA BELFIELD. LETTER. MONEY ORDER TO FOLLOW. REPLY.

Maddy stared at this turn-up, puzzled, and pushed it over for Ivy to read.

‘Who’s Prunella Belfield? What a funny name,’ she smiled.

‘She must be a relation I don’t know,’ said Maddy. ‘My grandma Belfield, I expect.’

Whoever she was, this relative expected a reply by return and there was nothing to stop her from going north. At least it would be far away from all terrors of the past weeks. There was nothing for her in Chadley now.

2 (#ulink_8dafadf7-a5b5-58da-aa4b-89bb245d7a02)

Sowerthwaite

‘They must be picked fast before the frost Devil gets them!’ yelled Prunella Belfield, burying her head into the blackberry bushes, while shouting instructions to her line of charges to fill their bowls to the brim.

It was a beautiful autumn afternoon and the new evacuees needed airing and tiring out before Matron began the evening bed routine in earnest.

‘But they sting, miss!’ moaned Betty Potts, the eldest of the evacuees, who never liked getting her fingers mucked up.

‘Don’t be a big girl’s blouse,’ laughed Bryan Partridge, who’d climbed over the stone wall to reach a better cluster of bushes, unaware that Hamish, the Aberdeen Angus bull, was eyeing him with interest from across the meadow.

‘Stay on this side, Bryan,’ Prunella warned, to no avail. This boy was as deaf as a post when it suited him. He had runaway from four billets so far and was in danger of tearing the only pair of short trousers that fitted him.

‘Miss…’ whined bandy-legged Ruby Sharpe, ‘why are the biggestest ones always too high to reach?’

Why indeed? What could she say to this philosophical question? Life was full of challenges and just when you thought you had it all sorted out, along came another bigger challenge to make you stretch up even further or dig deeper into your reserves.

Just when she and Gerald had settled down after another sticky patch in their marriage, along came the war to separate them. Just when she thought she was pregnant at long last, along came a second miscarriage and haemorrhage to put paid to that hope for ever.

Just when she thought they could leave Sowerthwaite and her mother-in-law’s iron grip, along came the war to keep her tied to Brooklyn Hall and grounds as a glorified housekeeper.

If anyone had told her twelve months ago she would be running a hostel for ‘Awkward Evacuees’, most of whom had never seen a cow, sheep or blackberry bush in their lives before, she’d have laughed with derision. But the war was changing everything.

When the young Scottish billeting officer turned up at Pleasance Belfield’s house, he stared up at the Elizabethan stone portico, the mullioned windows and the damson hues of the Virginia creeper stretched over the walls, and demanded they take in at least eight evacuees immediately.

Mother-in-law refused point-blank and pointed to the line of walking sticks in the hallstand under the large oak staircase.

‘I have my own refugees, thank you,’ she announced in her patrician, ‘don’t mess with me’ tones that usually shrunk minor officials into grovelling apologies. But this young man was well seasoned and countered her argument with a sniff.

‘But there is the dower house down the lane, I gather that belongs to you?’

He was talking about the empty house by the green. It was once the Victory Tree public house, but had been shuttered up for months after some fracas with the last tenant. It had lain empty, undisturbed, the subject of much conjecture by the Parish Council of Sowerthwaite in Craven, tucked away by the gates to the old Elizabethan manor. Not even Pleasance could wriggle out of this.

‘I have plans for that property,’ Mother countered. ‘In due course it will be rented out.’

‘With respect, madam, this is an emergency. With the blitz we need homes for city children immediately. Your plans can wait.’

No one talked to Pleasance Belfield like that. He deserved an award for conspicuous bravery. Her cheeks flushed with indignation and her bolster bosom heaved with disapproval at this inconvenient conversation. If ever a woman belied her name, it was Gerald’s mama, Pleasance. She ruled the town as if it was her feudal domain. She sat on every committee, checked that the vicar preached the right sermons and kept everyone in their proper places as if the twentieth century hadn’t even started.

The war was an inconvenience she wanted to ignore but it was impossible. There was not a flag or a poster or any recruitment drive without her approval, and now she was being faced with an influx of strangers and officials who didn’t know their place.

‘My dear fellow, anyone can see that place’s not suitable for children. It was a public house with no suitable accommodation for children. Who would take responsibility? I can’t have city ruffians racing round the streets disturbing the peace. Let them all be put up in tents somewhere out of the way.’

‘Oh, yes, and when a bomb drops on hundreds of them, will you take the responsibility of telling their poor mothers?’ he replied, ignoring her fury at his insolence. ‘We’re hoping young Mrs Belfield would see to things.’ The officer looked straight at Plum, giving her a look of desperation but also just the escape she needed from the tyranny of life with Mother-in-law and her gang.

‘But I don’t know anything about children,’ Plum was quick to add. Gerald and she had not managed to take a child to term and now that she was nearly forty, her chances of conceiving were very slim.

‘You’ll soon learn,’ said the billeting officer. ‘We’ll provide a proper nurse and domestic help. I see you have dogs,’ he smiled, pointing to her red setters, Sukie and Blaze, tearing round the paths like mad things. ‘Puppies and kiddies, there’s not much difference, is there? The ones we have in mind are a bit wayward, you see, runaways from their billets mostly. You look just the type to lick them into shape.’ The man winked at her and she blushed.

It was time she did some war work, and a house full of geriatric relatives hoping to sit out the war in comfort was not her idea of keeping the home fires burning.