По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

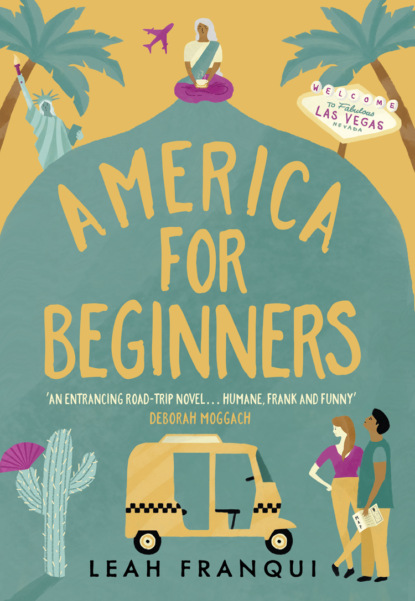

America for Beginners

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She heard a cough. “Thank you, Sarya, you can go.” Her voice had wavered but held firm, she thought to herself with no small amount of satisfaction. She heard Sarya sob petulantly behind her, and she knew this would be another piece of gossip for the servants’ quarters, the cruelty of madam, her refusal to even look them in the face.

Once Pival was sure that the girl was gone, she allowed herself to turn back and look at the meal she had been given. She noted that the cook had left her tea and a light repast of digestive biscuits, but no sugar or cream. They must not have thought she deserved those luxuries.

The quiet of the apartment felt strange. Normally it was a hive of activity, or it had been during Ram’s life. A host of people began to arrive as early as six in the morning, starting with the milkman who brought their milk daily, delivering to them first as the result of a few well-timed extra rupees each year. Then there was her breathing instructor, who arrived at seven; the yoga instructor, at eight; and at least three times a week a priest would arrive at nine to lead them in prayers and bless their shrine. Ram’s departure for work at ten would empty things out a bit but soon a stream of people delivering things would begin again, and then, of course, the visiting hours, the memory of which made her shiver despite the steam rising up from the cup of tea in front of her. The clock struck two, which meant teatime was upon her. Small wonder she felt uneasy, she thought, her mouth twisting. Although she had eliminated teatime the day Ram died, memories of it haunted her still. She looked around her, reassuring herself that she was alone.

When Ram had been alive tea had not been a beverage. Tea had been an event. Although Ram was rarely home at that hour, the timing of tea was strictly maintained in his absence. From two P.M. to five thirty P.M. a daily stream of visitors poured through the door, a stark contrast to the workers who entered in the mornings. They would include all the cousins, aunts, distant acquaintances, and close friends, implicitly demanding drinks and snacks and, most importantly, conversation. If not quite the cream of Bengali society, it was the richest milk of it, wealthy and well educated, and if not quite Brahmins, trying to make up for it at every turn. Ram, a barrister in Kolkata’s high court, was not expected to be present. In fact, his absence was a point of pride for his many female admirers, who beamed and remarked happily, “So busy he is with his work!” Between the countless cups of weakly brewed, milky tea and the vast amounts of commentary, Pival often felt like she was drowning in a caffeinated sea. She wished Ram would return home at two, at first because she missed him, and later because when he was there she could retreat and be permitted some relief and stillness.

She took a sip of her tea, savoring the simplicity of the liquid and the pure silence filling the room. She couldn’t help but think of all the teatimes that had felt endless, when she had watched the clock from the corner of her eye and groaned inwardly when the eagle-eyed gaze of disapproving relatives seemed to pin her in place.

Pival’s parents had raised her with gentle curation, like the caretakers of a small private museum. Her parents’ strict rationality and disdain for superstition had made them disapprove of blind adherence to any custom that could not be explained logically. Pival had grown up trusting herself and her own judgment, and it had come as an unpleasant surprise to find out that her husband and his large and ever-present family did not.

When they spoke to her, offering what they considered to be deeply helpful ways to improve her life, they did so with the assumption that she would already know their expectations, which left her confused, them disappointed, and Ram derisive. Her husband’s frustration at her inquiries about these rituals and habits, which seemed so natural and self-explanatory to him, submerged Pival further into silence. The quieter she became, the more he chastised her. Seeing how her husband treated her, his family followed suit. After a daily serving of their disdain, swallowed with her own snacks at teatime, Pival’s confidence had faded and died, replaced by a reserved meekness and deep inner pain.

And then there had been Ram, who had isolated her with his judgments. No one was ever good enough to be their friend, so now she had none. Who could measure up to the Sengupta standards? It had been easier not to argue, easier to just quit. Her brother had died in an accident when he was twenty-seven, so when her parents passed away, her last ties to anyone outside of the Sengupta clan had been effectively severed. Now, she realized, she knew no one else.

Pival took another sip of her tea, trying to force that pale shadow of herself back into the past. Stop haunting my living room, she told it in her mind. Today she was alone. She no longer had to bend and mold herself into the shapes others had left for her to fill.

After Ram’s death, many of her former visitors had maintained their teatime arrivals to comfort her in her time of need. At least, that was what they said they were doing, but Pival had been aware that their real goal was to ensure that her grief followed the prescribed paths set out for her by the Senguptas. Carefully they observed her, as if she were an animal at the zoo. Even in mourning there was a host of customs for Pival to neglect and perform incorrectly. That must give them a great deal of happiness, Pival thought, finishing her tea. Pival sometimes found herself speaking to her husband in her mind in a way she never could have in life. At least I’m good for something, Ram.

A crash and then the sound of angry protests floated up to her window. She returned to the balcony and looked down below. A car had collided into a cart full of supplies to decorate the goddess, and now brightly colored paper and paints and flowers filled the narrow road. The owner of the cart screamed at the driver, demanding compensation for his damaged goods. The driver, on the other hand, was furious at the injury to the car, which seemed to have suffered no ill effects that Pival could see, other than a few splatters of paint and a shower of flower petals. Certainly his vehicle would face more such damage during the festival itself, which flooded the city with people and left cars covered in its decorations for days.

Inside the car, the passenger was rapping loudly at the window, and the screaming driver’s face shifted instantly from angry to servile. He bowed to the car’s occupant, who had rolled down the window an inch or two and was slipping a slim handful of rupees rolled into a neat cylinder into the cart owner’s hand. The man accepted the compensation happily as the driver grumbled and spat a large stream of paan right at the cart owner’s feet. The driver resumed his position within the car, and the cart owner dragged his cart, now with a cracked wheel, in the other direction. The small street was silent once more, with only the spattered remains of the decorations as evidence that anything had happened. A flicker of movement caught her eye. There was a child crouched in the gutter, begging. She hadn’t even noticed.

When she was young, Pival had loved Durga Puja, but as an adult all the joy of the holiday had died for her the day that Rahi left. Without him in the house, her celebrations felt hollow. Rahi had always loved to take his lantern and dance in front of the goddess, thanking her for her triumph over the evil demon and imploring her for her grace. Ram would watch, disapproving of his son’s dancing but unable to say anything because it was traditional. Once Rahi was gone they didn’t decorate their house or their shrine; instead they visited with others during the holiest days of the event, leaving their own house empty and allowing the servants time off.

She had thought she had nothing to thank the goddess for this year, but as she watched the empty street she realized Durga Puja was giving her the opportunity to escape. It would be like the child in the road. People would be so distracted by the festival that they would never see her slip away. She watched the child scratch at his scabs and made a mental note to send down some food from the kitchen if there was extra. The cook had yet to learn how to prepare meals for Pival alone, and they always had too much. The child would have something to eat that night, at least.

Why had Mr. Munshi not returned her calls? Was there some problem with the guide, or worse, the companion? Mr. Munshi, whom Pival would not want to insult but who sounded vaguely Bangladeshi to her, had assured her, “All is possible, probably, prepared, madam!” Now she feared that this was not the case. Her tickets had been booked. She left in a week, at the height of the festival. What would she do if there were no tour guide and companion waiting? She hated to admit it but Tanvi’s dire warning echoed in her brain.

She wished she had kept more of herself whole throughout her long marriage. She could have used her youthful boldness now, but it was gone. In its place was fear, and what could that help her now? She thought about Rahi. Why had he left her all alone? What had he found in America?

4 (#ulink_df75931e-b827-500b-8325-ad671794fafd)

Jacob Schwartz fell in love for the first time sitting in a traffic jam on the way back from the airport and it was only because of the horrible congestion of the Los Angeles freeway that he realized it. If he had lived in another kind of place, who knows what might have been possible? But he looked over at the face next to him, the strong jaw, the straight nose, the smooth tanned skin, and the mouth stretched wide as Bhim belted out a power ballad from the early nineties, and there it was. Love. They were two miles from their exit and in the half an hour it took to travel that distance Jake had convinced Bhim to kiss him back, and by the time they reached Jake’s apartment their inhibitions were long gone, as were their shirts.

For as long as he could remember, Jake’s life had been dictated by traffic. He had grown up in Los Angeles, so commuting had been a way of life. His mother, a divorcée and part-time yoga teacher living in Venice Beach, had carted him from school to guitar lessons to soccer practice to the mall to movies and finally, three nights a week, to his father’s condo in East Hollywood for awkward meals from nearby Chinese food takeout joints. Together he and his father would eat moo shu chicken in silence, with his father’s tentative overtures met with surly rebuffs. What they talked about, because they couldn’t talk about anything else, was traffic. How to get where, what route they had taken that day, what its potential benefits and downsides were. Traffic was the language of neutrality in Los Angeles and Jake learned it young.

The early years after his parents’ separation, which occurred just after his tenth birthday, had been filled to the brim with activities, as if his life could be made too full for him to notice the difference. Jake, as he had been called by everyone in his life but Bhim, had observed his parents carefully after they split up, like a scientist monitoring a long-term experiment, noting changes and constants, variations and radical outliers. He kept a diary with carefully maintained charts, as he was, according to all his teachers, a visual learner. His ultimate conclusion, after several years, was that in fact the best situation for them all was this, for his parents to live in two separate bubbles, with Jake as the only connection between them. This hadn’t stopped Jake from craving a partner, however, though it did make him wary about finding one.

Like many children of divorce, Jake was so good at telling the story of his family that by the time he was an adult he could gauge which detail would amuse his listener the most and play to it. When he had first met Bhim through mutual friends at a bar outside of San Francisco called Bangers and Mash, which served neither, their conversation had eventually shifted from hours of discussion on the nature of monotheism, marine life, and architecture to Jake’s family. When Jake had cheerfully described the divorce, wringing it for the kind of humor he thought this quiet Indian graduate student might enjoy, Bhim had turned pale and quite seriously apologized to Jake for his “broken home.” Jake, having never heard that phrase outside of Lifetime original movies, laughed hysterically. His home was far from broken, he gently explained to Bhim. The other man looked at him with such compassion in his eyes, and Jake had to admit, he couldn’t help but lean into it, hoping it might turn into something more.

There was something about Bhim that was completely hidden from Jake, and although it should have driven him insane, he loved it. Right off the bat, Jake could tell that Bhim had the gift of real empathy, something Jake always worried he lacked. Bhim could put himself in the shoes of any person; he could get complete strangers to speak to him about their lives, their fears, what lived in their hearts, all without sharing anything of himself. He had perfected the art of imitating a deep conversation, all without the other participant’s ever realizing that it was entirely one-sided.

To Jake, right from that first conversation, Bhim seemed so apart from things, his own island. He was unexplored territory, and Jake wanted to be the explorer.

Bhim had never dated a man before. In fact, he had never dated anyone before. Although men were what he wanted, or rather, what his heart desired, as he told Jake in his serious way, it felt wrong to him, because he knew, as he had been taught, that it was unnatural to feel this way. As the bar lights flickered around them and the once-roars of the crowd turned to the murmurs of a handful of other patrons, Bhim told him that while he wanted Jake, he knew that this was because he had lost his morality under the influence of America, and he didn’t want to become corrupt for his whole life, the way Jake was. He put his hand on Jake’s knee and Jake felt the warmth of his palm radiate through his body as Bhim asked him if he would be with him for one night only, so that Bhim would know what it was like before he agreed to marry a woman.

The scent and feel of this man so close was intoxicating to Jake. He had been with others before, but something about Bhim resonated with him in ways no one else ever had. Perhaps it was the fact that this was the first crack in Bhim’s reserve, the first spark of emotion he had displayed. Or perhaps it was the way Bhim said such horrible things in such beautiful ways, the smooth tenor of his voice and slurring affect of his accent making bigotry sexy. He could almost forget what was being said and concentrate solely on the mouth that was saying it.

Jake had been more than a little afraid to come out to his parents. It wasn’t that Jake’s parents had ever expressed the opinion that homosexuality was in any way negative. They had gay friends, knew gay couples, described gay people in their lives with the same adjectives and nouns they would have used for anyone else. Nevertheless, Jake had no idea what their reactions would be when they heard it from their own child. He had never dared displease his parents in any respect during his entire young life. He had had a Bar Mitzvah for his father, and spent vacations in spas devoted to raw foods and meditation with his mother. He was the poster child for a happy product of an unhappy union. What would they think of him now?

But it turned out what they thought of him was exactly the same as it always had been. And from the day he came out, life was fairly simple. Jake was what he was, and anyone who didn’t like it could go to hell, including those who remained closeted themselves.

The first time he had ever even questioned that was when he met Bhim, the boy in the bar in Berkeley. Jake wanted to give Bhim what he wanted. He wanted to do it for his younger self, the child of wealthy liberals who nevertheless was petrified of being an outcast. He knew what it was to wish you were something different even when it was the thing that made you yourself.

But he also knew even in those first moments that one night wouldn’t be enough. He wanted possession, to have Bhim totally, and that could never happen if it was just an experiment, a way for a closeted man to tell himself he was over his youthful folly.

So when Bhim, drowsy and bold, with the scent of a mojito on his breath, asked him if he would be with him for that night and that night alone, Jake removed Bhim’s warm hand on his thigh and shook his head. He walked away from the handsome young Indian man with the soul of a guru and the eyes of a supplicant, and forced himself not to look back.

After he had returned to Los Angeles, Jake thought about Bhim often. He saw Bhim’s face in his daily runs and during his drive each day to work, as he sketched blueprints and researched indigenous plant varieties. He could not rid himself of Bhim’s eyes; they floated in Jake’s mind as he tried to sleep, dark and enticing. They blinked at him, big, widely set, lushly fringed cow’s eyes, and he thought he could see tears in their corners and woke up crying himself for no reason. When he checked his email several weeks after his trip to San Francisco and saw a message from a Bhim Sengupta he was thrilled, and terrified. Bhim was sorry; he had begged for Jake’s email from the friend who had introduced them (who, when Jake interrogated him later, admitted that he had always thought Bhim, closeted though he was, would be a good fit for Jake) and just wanted to apologize. No, more than that, he wanted to be friends. Jake felt sick. He responded anyway, thinking himself an idiot and not caring.

They began by emailing, once or twice a week, then daily. In writing, Bhim was freer than he had been in person, giving little glimpses into his thoughts, displaying new things in each message: a wicked yet silly sense of humor, a love of nature, a fear of snakes. The communication came in waves, inundating Jake with information, with questions, with thrills up and down his spine. Soon came texts and phone calls, and before long they were wishing each other good night and sending each other photos in increasing states of undress. Jake had started it, being the bolder one of the pair, but Bhim surprised him with his own images, his responses, and his tentative innovation.

Then, as suddenly as it had begun, it stopped. It was as if Jake had been an imaginary friend that Bhim had played with for a while but no longer needed. Jake tried not to care, he tried to remember that Bhim was from a different culture, that he was closeted and racked with self-hatred, and that they hadn’t been dating, they hadn’t been anything, really. But it hurt. It hurt everywhere, like sleeping on a sunburn. Jake started agreeing to dates with anyone who even thought about asking. After one, a brunch in downtown Los Angeles, Jake was driving home, cursing the traffic, when he got a call from Bhim, who was at the airport, waiting for Jake to pick him up.

When Jake saw Bhim on the sidewalk by Arrivals, Bhim’s face was as stiff as a mask. Jake looked at him for a moment, waiting for his eyes to flicker with affection, recognition, anything. It was like watching a statue come to life, the way expression poured into Bhim’s face as he saw Jake. Jake wondered if this was why he liked Bhim so much, the way he felt like maybe Bhim was coming to life just for him.

They didn’t say much to each other in the car. There were many smiles, tentative and deeply aware. There were no apologies or explanations. Bhim had a small bag, and he informed Jake that he would be spending the weekend with him. There was nothing more to say. Instead, Bhim sang along with the radio. It was the second time they’d met in person, and Jake knew it was love.

Bhim had never had sex with anyone before, man or woman, which he confessed once they had survived the Los Angeles traffic and were standing in Jake’s immaculate bedroom, with its coordinating shades of blue and gray. Jake had lowered the blinds and curtained the windows, but Bhim still looked at them like they might let the whole world in to see him. Jake thought of his first times, his drunken nights in college dorms and his pain afterward, and he vowed to himself that he would make this good for Bhim, that they would go slow and enjoy everything. Bhim lasted all of five minutes into their naked foreplay before he spent himself on Jake’s coverlet. They spent the rest of the evening doing laundry and eating Chinese food and trying again, and again, until it was good, for both of them, better than good, it was perfect. Jake bit back the words he wanted to say and enjoyed sleeping next to someone, but he couldn’t help but think about the way Bhim had looked at the airport before he had seen Jake, like a dead person, like someone who was already gone.

5 (#ulink_d065c224-d948-5c35-8b5b-8c8f48a00773)

Pival always blamed herself for her marriage, for the way it became and the way it began. Pival had been the first one to say hello, in a fashion. Ram Sengupta had been sitting in the canteen, reading her university newspaper. It was very much her university newspaper, as Pival was the editor, a fact that her delighted father would recount to anyone he could force to listen. Ram Sengupta, then thirty years old and somehow, to the grave distress of his family, unmarried, had picked up a copy of the Calcutta College Courier with amusement as he waited for his friend Charlie Roy, a professor teaching at the school, who was always late.

Pival, young and alive with purpose, watched this tall, slim, yet commanding stranger sneer at her paper and saw red. Who was this man? What did he know of journalism? She could not stand by and watch him scorn her hard work, her long nights of setting type and editing articles. A closer look revealed that this stranger, handsome as he was, was laughing at her own article, a piece she’d been quite proud of, detailing the city’s architecture as a troubling metaphor for the continued influence of British colonialism on Indian mentality and cultural consciousness. Her article was cautiously tinged with Naxalite rigor, coated in intellectual argument, and she was deeply proud of it. Pival was not one to stand by while her work was being impugned in such a cavalier manner. She marched up to this strange man and asked him in polite and careful English:

“What, exactly, is so very funny?”

Ram Sengupta looked up at this serious young woman, with her dark eyes glinting, and asked her to join him for tea. Pival was so flustered that she sat down without another word. When Charlie Roy finally showed up some thirty minutes later, he found his friend, a confirmed bachelor, assessing his future wife.

The two fused into a unit almost immediately. Ram’s authority destroyed Pival’s own sense of herself and replaced it with a version that Ram created, a version she liked better, for a time. For Pival’s part she had never met a man who looked at her with such a mix of calculation and interest, and she mistook his manipulative speculation for a deep true love. So, for that matter, did he. They were engaged within a month.

Looking back on her excitement at the time, Pival cursed herself for being ten times a fool. She had thought Ram would be the antidote to the loneliness and longing she had begun to feel. Instead, he became the cause of both. She had thought for a while that her marriage was normal, no worse than many, better than most. But it had proved weak, and in the end, rotten to the core.

But Ram was gone now. And she could have her son back, just as soon as she could wrench him from the grasp of the man in California. They could be together. And if he was really gone, if it hadn’t been, as she hoped, a kindly meant act that pierced her heart with its cruelty, she could die with Rahi. Even if she couldn’t live with him.

6 (#ulink_5b220f44-08f5-5773-8300-b694a9f21916)

The morning after Jake and Bhim had slept together for the first time, Jake, as he had done every morning for the last twelve years, took a run. His lifetime of waiting in traffic had bred in him a need for movement. He had run through college, through his early twenties, and even now, curled up in the arms of a man he wanted and hadn’t known he could have, his muscles still tensed and prepared themselves. He shifted carefully in Bhim’s embrace, inching out of it in slow degrees, and then, grabbing his shorts and his phone, he escaped the room and was gone, his feet pounding the pavement as he moved with tireless joy through the morning haze of the city.

On his daily runs, Jake would often see remnants of the Los Angeles nightlife haunting the city and wincing in the harsh light of the sunrise. What hurt their eyes made his glow; he loved the mornings. Jake worked for a large architecture firm located in downtown L.A., which catered to the elite and the effete, as his bosses liked to joke. The firm included both landscape architecture and residential and commercial work, and often attracted clients interested in combined design, updating or creating new spaces that integrated natural design as well as buildings. Jake worked in the landscape department. He enjoyed any work that took him outside, that had him under the sun for hours on end. He loved the smell of dirt and the way plants anchored into it.

After college, Jake had floated for a bit, uncertain what he wanted to do next. He had enjoyed working on Brown’s organic farm so he got a job at the New York Botanical Garden as a researcher. But he soon realized that biology wasn’t as interesting to him as space, and the way plants and buildings could fill it. He enrolled in architecture school the following fall. Within two years he had his master’s and, weary of the East Coast winters, chose a job in Los Angeles, to the delight of his parents, and started working at Space Solutions. Once he settled into that it seemed that he settled into everything. Life became pleasant, compartmentalized, and predictable. The job was good, the people were nice, the high school friends who like him had come back were happy to reconnect, the guys he met were fit and a little dim, but open and friendly and never hard to catch or lose. His apartment was spacious, his world was small.

Now someone had joined him, and the apartment no longer was empty. Suddenly he wondered why he was running away from home, not toward it. What would Bhim say, when he woke up? Would he regret this? Jake’s breath caught in his chest. This had been one of the best moments of his life, the first time he had felt truly with someone else, in sync with him. What if Bhim hated what they had done, what if he woke up horrified with Jake and with himself? He tried to shake off these thoughts, to run again, but his feet had turned to lead. He walked home, dragging his body the few blocks back to his apartment, and opened the door with dread.

Bhim was still in the bed, sleeping. His lashes formed spiky uneven crescents on his cheeks and Jake felt a sense of relief that there was something in Bhim’s face that wasn’t perfect. He watched him sleep deeply and got into the shower. Jake washed himself off briskly, trying to ignore the fear that had struck his heart. What if, what if, what if resounded in his brain and he wished he could drown out the noise of his worries. He almost wanted to wake Bhim up, to face his judgment and his disgust sooner rather than later, but each moment gave him more time to feel like they were together.