По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

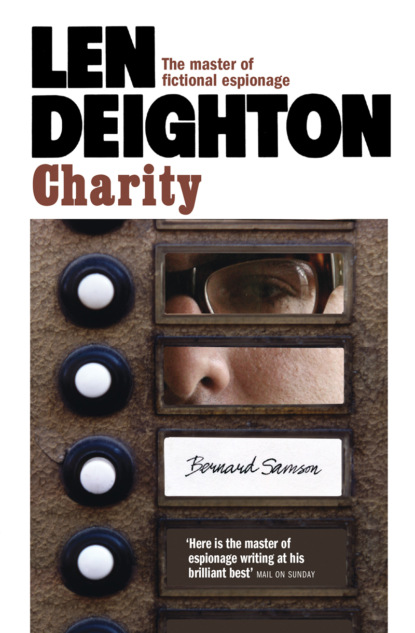

Charity

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Did the cat eat them willingly, or did you dose it?’

‘What are you getting at?’ he said indignantly. ‘I didn’t choke the cat, if that’s what you mean. I was dosing farm animals before you were born.’ I’d forgotten how highly he cherished his credentials as a country gentleman.

‘If it was a very old cat …’

‘I don’t want you discussing this with my daughter or with anyone else,’ he ordered.

‘Was this what you wanted to ask me?’ I said. ‘The dead cat and whether to report it?’

‘It was one of the things,’ he admitted reluctantly. ‘I wanted to ask you to take a note of it off the record. But since then I have decided that it’s better all forgotten. I don’t want you to repeat it to anyone.’

‘No,’ I said, although such a stricture hardly conformed to the way in which he identified me with the powers of government. I recognized this ‘confidential anecdote’ about his son-in-law’s homicidal inclinations as something he wanted me to take back to work and discuss with Dicky and the others. In fact I saw this little cameo as David’s way of hitting his son-in-law with yet another unanswerable question, while keeping himself out of it. The only hard fact I could infer from it was that David and George had fallen out. I wondered why.

‘Forget it,’ said David. ‘I said nothing, do you hear me?’

‘It’s just a family matter,’ I said, but my grim little joke went unnoticed. He was still standing in the window, and now he turned his head to look out at the garden again. Fiona and the children were heading back. Seeing David profiled, and in conjunction with the snowman at the bottom of the lawn, I wondered if the children had intended it to be a caricature of their grandfather. Now that the belly had been restored and the shoulders built up a little it had something of David’s build, and that old hat and walking-stick provided the finishing touches. It was something of a surprise to find that my little children were now judging the world around them with such keen eyes. I would have to watch myself.

‘They’re growing up,’ said David.

‘Yes, I’m afraid so.’

He didn’t respond. I suppose he knew how I felt. It wasn’t that I liked them less as grown-ups than as children. It was simply that I liked myself so much more when I was being a childlike Dad with them, an equal, a playmate, occupying the whole of their horizon. Now they were concerned with their friends and their school, and I couldn’t get used to being such a small part of their lives.

‘I’ve got two suitcases belonging to that friend of yours.’ David meant Gloria of course. ‘When she brought the children over here to us, she left two suitcases with their clothes and toys and things. Expensive-looking cases. I don’t know where to contact her, apart from the office, and I know you people don’t like personal phone calls to your place of work. I thought perhaps you would be able to take them and give them back to her.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I don’t go to the London office, I work in Berlin nowadays.’

‘I didn’t want to ask Fiona.’

He displayed characteristic delicacy in not wanting to ask Fiona about the whereabouts of my one-time mistress. He didn’t really care of course. The question about the suitcases that Gloria had left with him was just a warning shot across my bows. Now he got on to more important matters.

‘She’s still not well.’ He was looking at Fiona and the kids.

‘She’s tired,’ I said. ‘She works too hard.’

‘I’m not talking about being tired,’ said David. ‘We all work too hard. My goodness …’ He gave a short laugh. ‘…I’d hate to show you my appointments diary for next week. As I keep telling those trade union buggers, if I worked a forty-hour week I’d be finished by lunchtime Tuesday. I haven’t got even a lunch slot to spare for at least six weeks.’

‘Poor you,’ I said.

‘My little girl is sick.’ I’d never heard him speak of Fiona like that; his voice was strained and his manner intense. ‘It’s no good the pair of you telling each other that she’s just tired and that a relaxing holiday and a regime of vitamin tablets are going to make her fit and well again.’

‘No?’

‘No. Tonight we have a few people coming to dinner. One of the guests is a top Harley Street man, a psychiatrist. Not a psychologist, a psychiatrist. That means he’s a qualified medical man too.’

‘Does it?’ I said. ‘I must try and remember that.’

‘You’d do well to,’ he said gruffly, suspecting that I was being sarcastic but not quite certain. He moved away from the window and said: ‘He agrees with me; Fiona will never be fit enough to take charge of the children again. You know that, don’t you, Bernard?’

‘Has he examined Fiona?’

‘Of course not. But he’s met her several times. Fiona thinks he’s just a drinking chum of mine.’

‘But he’s been spying on her.’

‘I’m only saying this for your sake, and for the sake of Fiona and your wonderful children.’

‘David. If this is a prelude to your trying to get legal custody of the children, forget it.’

He sighed and pulled a long face. ‘She’s sick. Fiona is slowly coming round to face that truth, Bernard. I wish you would face it too. You could help me and help her.’

‘Don’t try any of your legal tricks with me, David.’ I was angry, and not as careful as I might have been.

With an insolent calm he said: ‘Dr Howard has already said he’d support me. And I play golf with a top-rate barrister. He says I would easily get custody if it came to it.’

‘It would break Fiona’s heart,’ I said, trying a different angle.

‘I don’t think so, Bernard. I think without the children to worry about she’d be relieved of a mighty weight.’

‘No.’

‘Why do you think she’s been putting it off so long? Having the children back with her, I mean. She could have come down here as soon as she returned from California. She could have taken the children up to the apartment in Mayfair – there are spare bedrooms, aren’t there? – and made all the necessary arrangements to send them to school and so on. So why didn’t she do that?’ There was a long pause. ‘Tell me, Bernard.’

‘She knew how much you both liked having the children with you,’ I said. ‘She did it for you.’

‘Rather than for you,’ he said, not bothering much to conceal his glee at my answer. ‘I would have thought that you would have liked having the children with you, and that she would have liked having the children with her.’

‘She loves being with them. Look at her now.’

‘No, Bernard. You can’t get round me with that one. She likes coming down here to see the children. She’s pleased to see them so happy and doing well at school. But she doesn’t want to take on the responsibility and the time-consuming drudgery of being a Mum again. She can’t take it on. She’s mentally not capable.’

‘You’re wrong.’

‘I’m surprised to hear you say that. According to what Fiona tells me you yourself have said all these things to her …’ He waved a hand at my protest. ‘Not in as many words, but you’ve said it in one way or another. You’ve told her repeatedly that she’s trying to avoid having the children back home again.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I never said anything like that.’

He smiled. He knew I was lying.

David’s dinner party seemed as if it was going to last all night. He was wearing his new dinner suit with satin lapels, and his patent Gucci loafers with red silk socks that matched his pocket handkerchief, and he was in the mood for telling long stories about his club and his golf tournaments and his vintage Bentley. The guests were David’s friends: men who spent their working week in St James’s clubs and City bars but made money just the same. How they did it mystified me; it wasn’t a product of their charm.

By the time the dinner guests had departed, and the family had exchanged goodnights and gone upstairs to bed, I was pretty well beat, but I felt compelled to put a direct question to Fiona. Casually, while undressing, I said: ‘When do you plan to have the children living with us, darling?’

She was sitting at the dressing-table in her nightdress and brushing her hair. She always brushed her hair night and morning, I think it was something that they’d made her do at boarding school. Looking in the mirror to see me she said: ‘I knew you were going to ask me that.’

‘Did you?’

‘I could see it coming ever since we arrived here.’