По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

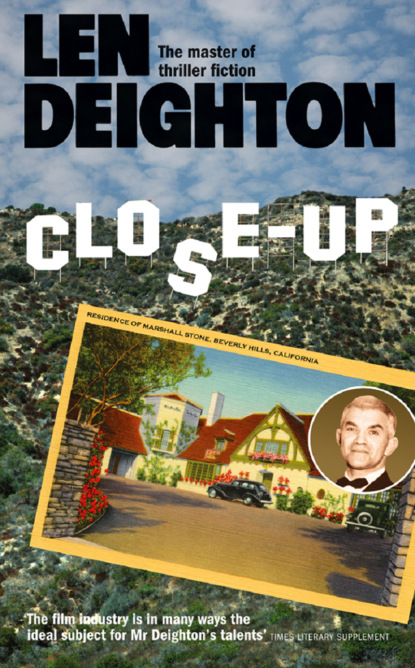

Close-Up

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What?’

‘Take it from you. Winning the role fair and square: yes. I’ll fight you tooth and nail for the part, but I don’t want the part as a last resort of a nervous flack.’

‘Don’t be so stupid. If I don’t get it and then you turn it down they’ll give it to some other actor. Where does that get me.’

‘I’ll not take it, Edgar. You’ll see. These Hollywood bastards behave like Lorenzo the Magnificent, it will do them a power of good to hear an actor telling them to stuff a contract. Screw Hollywood!’

‘I could never live here,’ said Nicolson.

‘The stage,’ said Stone. ‘An actor needs the stage and an audience. The juices drain out of a man who spends his days transfixed by a bloody one-eyed machine.’

‘I like films –’ said Nicolson.

‘Films,’ said Stone. ‘Yes, we all like films. If you are talking about De Sica and Visconti. If you’re talking about Bicycle Thieves or Open City: everyone likes real films about real people in true life conditions.’

‘But there’s a new realism here in films –’

‘Hollywood films are about murderers, psychopaths, gunmen. What I’m talking about is the starkness of Bataille du Rail, the poetry of Belle et la Bête. No, Hollywood is a fine place to earn some money and to see some great professionals at work, but Englishmen like us are rooted in European culture. We die if we stay out here. Look around you, look at the limeys who live here.’

‘You think so?’

‘Sure of it. You charge your batteries in the theatre – here you just flash the headlights.’ He nodded. ‘What are you drinking, Edgar. It is Edgar?’

‘Diet soda. Yes, Edgar Nicolson.’

‘What you want is strong black coffee with a slug of something in it.’ He took a hip flask from his jacket and poured both coffee and brandy. ‘And stop looking so bloody worried, Edgar. We English have got to stick together. Am I right? Stick together and we can beat the bastards.’

Until that moment Nicolson had still been confident that the part he wanted would be his. Nicolson had the right build for a cowboy, a better walk and his voice was far far better than this fellow’s. But now he knew that Stone would stop at nothing to wrest the part from him. He’d been in the profession long enough to know the desperation with which actors fight to secure work but usually they had been crude oafs who could not stand up to Nicolson or measure up to his skills. Stone was not just another stupid actor. He was as smooth and as hard as an aerial torpedo and just as dangerous, but not perhaps as self-destructive. Stone surely didn’t expect Nicolson to believe that soft soap about turning the offer down, it was his way of declaring that he was going to do battle. Stone smiled a silky smile.

Nicolson said, ‘Yes, we must all stick together,’ and then he pushed the coffee to the far side of the table. If Bookbinder smelled the alcohol he would be marked down as a lush, and that was enough to lose him the part without this stupid girl going dramatic on him. Stone noticed him move the coffee. ‘Don’t feel like it, eh?’

‘I get tense,’ said Nicolson, ‘and then my stomach just rejects everything.’

‘I understand,’ said Stone. He understood.

A dish broke in the kitchen and there was a brief snatch of Spanish. The swearing was quiet and ritualistic as if there were too many breakages for a man to waste much energy on any one of them.

Bookbinder came back to the car with the doctor. They stood outside talking, and then the doctor went away. When Bookbinder came back inside, he poured himself coffee from the Silex on the burner and drank a lot of it before he spoke. ‘It’s happened before, Edgar, and it will happen again. The studio publicity guys spend more time keeping news out of the papers than getting it in.’

Nicolson said, ‘She took an overdose, you said?’

‘The whole bottle. The label of the studio pharmacy on it.’

Stone said, ‘Are you going to remove the bottle?’

‘That’s another department.’ Bookbinder pulled the curtain aside as another Ford arrived. The door pinged and a young curly-haired man entered. He wore a dark-blue wind-cheater, flannel trousers and white sneakers. He looked like a young stockbroker on vacation, or a half-back who’d broken training. Already he was showing the plumpness about the face and arms that predicted the huge middle-aged man he was to become.

‘Weinberger! Am I glad to see you,’ said Bookbinder.

‘Wie gehts?’ said the young man. Bookbinder nodded but was not amused. ‘You really screwed up a heavy date.’

‘Complain to Nicolson,’ said Bookbinder, ‘it’s his party.’

‘I want to see her,’ said Nicolson.

‘Sit down and shut up,’ said Weinberger. He put his hand on Nicolson’s shoulder and pushed him down on to his seat. ‘You do exactly what you are told and you might come out of this unscarred. First, her real name.’

‘Rainbow,’ said Nicolson, ‘Ingrid Rainbow.’

‘So why did she check in as Petersen?’ asked Weinberger harshly. It was a new side of Weinberger that Stone and Nicolson were seeing: he frightened them.

‘I don’t know. Perhaps that’s –’

‘You stick to not knowing. I don’t want you doing any guessing.’

‘Can I see her?’ said Nicolson.

Weinberger shook his head.

Edgar didn’t protest. He wanted to see the poor child. He wanted to talk to her, reassure her and tell her that he was worried. But he didn’t want to do it right now. The atmosphere was not sympathetic; even if Stone and Bookbinder remained here he would still be inhibited by them.

‘The doc’s been?’ said Weinberger.

‘That will be OK,’ said Bookbinder.

Bookbinder turned in his seat, stubbed out his cigar and bit his lower lip. Weinberger said to Nicolson, ‘You’ve visited her here? Here at the motel? The receptionist would recognize you?’

Nicolson nodded.

‘Oh well,’ sighed Weinberger, ‘we’ll sort that one out too.’ He nodded to Bookbinder.

Weinberger got up and steered him across the room to the service door. As they went through it there was a smell of burned fat and the strangled scream of a mixer. Just inside the kitchen Weinberger leaned close to the producer and gestured angrily. The service doors flapped, each swing providing a frame of a jerky old film. Nicolson knew they were deciding.

Eddie Stone was sitting well back from the table on the far side from Nicolson. He caught his eye and Stone smiled. As a child, Stone’s smiles had been nervous ones, but he’d soon learned the advantage of preceding all his remarks with an unhurried smile. ‘I didn’t know about it, Edgar. I was with Kagan when you phoned.’ He moved his chair back even more. Nicolson felt like telling him that whatever the trouble was, it wasn’t contagious. But they both knew it was. Nicolson looked at the service door. He could see the feet of the gods.

Weinberger said, ‘It’s not impossible to do it the other way: it’s tricky but not impossible, Kagan.’

‘What the Nicolson kid does once, he’ll do again. If Stone fouls up we can both say we’re surprised. But if Nicolson even gets a parking ticket, front office will want our balls.’

‘I’ll try to keep them both out of it.’

‘I know you will. You talked to New York?’

‘I can’t get New York for a couple of hours. But if you say Stone, he’ll stay as clean as a whistle. I promise.’

‘Stone,’ said Bookbinder and nodded.

‘Whatever you say,’ said Weinberger. Bookbinder grabbed him as he began to turn away. He reached for the top of the half-door and pulled it closed. ‘Don’t give me that, you bastard!’