По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

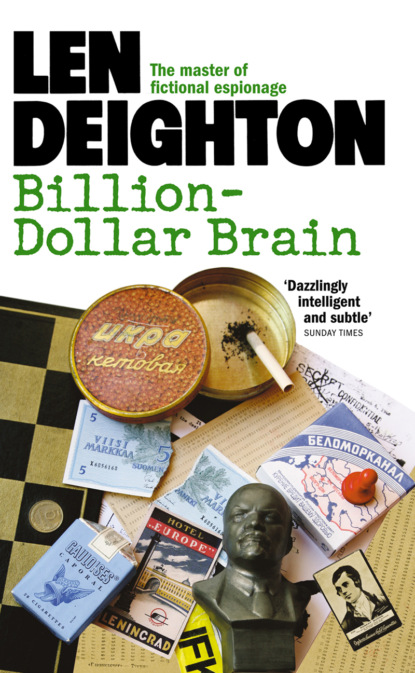

Billion-Dollar Brain

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Fine,’ said the man in gardening clothes. He lit his cigar with care and sat down in a hard chair to avoid soiling the chintz.

Dr Felix Pike said, ‘I see our Corrugated Holdings dropped a packet, Ralph.’

Ralph exhaled without haste. ‘Sold Thursday. Sell while they’re rising; don’t I always tell you that? Certum voto pete finem, as Horace says.’ Ralph Pike turned to me and said, ‘Certum voto pete finem: set a limit to your desire.’ I nodded and Dr Felix Pike nodded and Ralph smiled kindly.

Ralph said, ‘When I go public I’ll look after you, never fear. I’ll give you a green form, Felix. And hold on to them this time. Don’t do an in-and-out as you did with the Waldner shares. If you want a word of advice: unload your coppers and tins; they’re going to take a nasty drop. Mark my advice, a nasty drop.’

Dr Felix Pike didn’t like taking advice from his younger brother. He stared at him fixedly and moistened his lips with the tip of his tongue.

Ralph said, ‘You should remember that, Felix.’

‘Yes,’ said Dr Felix Pike. His mouth slammed down like a guillotine blade. It was a nasty mouth, an all-or-nothing device that closed like a trap, and when it opened you expected a greyhound to leap out.

Ralph smiled, ‘Been down to the boat lately?’

‘Was going today.’ He stabbed a thumb at me as though soliciting a ride on a lorry. ‘Then this came up.’

‘Bad luck,’ said Ralph. He pinged my empty goblet with his fingernail. ‘Another?’

‘No thanks.’

‘Felix?’

‘No,’ said Dr Felix Pike.

‘Did Nigel like the sub-machine gun?’

‘Loved it. He wakes us up every morning. I’m not supposed to thank you because he’s writing to you himself; with chalk on brown paper.’

‘Ha ha,’ said Ralph. ‘Arma virumque cano.’ He turned to me and said, ‘Of arms and the man I sing. Virgil.’

I said, ‘Adeo in teneris consuescere multum est. As the twig is bent the tree inclines. Also Virgil.’ There was a silence, then Dr Pike said ‘Nigel loved it’ again, and they both stared at the garden. ‘Do have another,’ Ralph offered.

‘No,’ said Dr Felix Pike. ‘I must change, we have people coming.’

‘Mr Dempsey will be wanting the package,’ said Ralph, as if I wasn’t listening.

‘That’s right,’ I said, to prove I was.

‘Good man.’ He kissed the cigar affectionately but fearfully, as if there was a good chance it might explode. ‘I brought it today,’ he said. ‘It’s switched on.’

‘Good,’ I said.

I reached into my back pocket and produced my torn half of the five-mark note. Dr Felix Pike walked across to one of the illuminated nooks. He moved two soft-focus portraits of his wife, another of those shiny brown spheres that I’d seen at the surgery – and finally found his half of the note under one of the Staffordshire figures that were drawn up in ranks along the glass shelves. He passed the half banknote to his brother Ralph, who fitted the two halves together in the same casual but careful way that he had handled the spade and cigar.

‘Right,’ he said, and went to get my half-dozen eggs for Helsinki. The package was wrapped in that plain discreet green paper that Harrods use. It was tied with a little loop to carry it. Before we left Ralph said that coppers would take a nasty drop again.

Dr Pike would like very much to have given me a lift back to the centre of town but … I understood, didn’t I? Yes. I took a bus.

The fog had become thicker and was that sort of green they call a ‘pea-souper’. The shoe shops were prisms of yellow light and past them buses were trumpeting, ambling aimlessly like a herd of dirty red elephants looking for a place to die.

I held the green-wrapped package on my knees and developed a distinct impression that it was ticking. I wondered why the second Mr Pike had said it was switched on but I didn’t intend to find out the hard way.

Waiting for me at Charlotte Street was one of the ‘bombers’.

‘Here it is,’ I said. ‘Easy does it, I’d like to deliver it in one piece.’

‘I’m not taking chances today,’ said the duty bomber. ‘I’ve got a steak-and-kidney pudding waiting for me tonight.’

‘Take your time,’ I said. ‘It’s the long slow simmering that produces the flavour.’

‘You got a little huffy last night,’ Dawlish said.

I said, ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be,’ said Dawlish. ‘You were right. You have instinct that comes from training and experience. I won’t interfere again.’ I made noises like a man who doesn’t want compliments.

Dawlish smiled. ‘I don’t say I won’t have you fired or transferred, but I won’t interfere.’ He toyed with his fountain-pen as though uncertain how to break the news. ‘They don’t like it,’ he said finally. ‘The written memo went to the Minister this morning.’

‘What did the memo say?’

‘Precious little,’ said Dawlish. ‘One sheet of foolscap double-spaced. I pretended it was a précis.’ He smiled again. ‘We’ve known about this organization run by Midwinter but we’ve never had it linked to this country before. Both these Pike brothers are Latvian; they hold extreme right political views and the one named Ralph is a top biochemist. That’s what the memo said and it worried the Minister sick. I’ve been over there twice today and neither time did I have to wait longer than three minutes. It’s a sure sign. Worried sick.’ Dawlish tutted and I tutted in sympathy. ‘Stick close to your friend Newbegin,’ said Dawlish. ‘Get into this Midwinter organization and take a good look at it. I only hope yesterday won’t make it dangerous for you.’

‘I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘The Americans are not spiteful, whatever other faults they have.’

‘Good,’ said Dawlish. He poured me a glass of port and talked about the set of six dram glasses he had bought in Portobello Road.

‘Might be eighteenth-century. They call that trumpet-bowled, see?’

‘Great,’ I said. ‘But aren’t there only five glasses?’

‘Ahh! Set of six with one missing.’

‘Ahh,’ I said.

Dawlish’s squawk-box buzzed and the bomber’s voice said, ‘Can I talk, Mr D?’

‘Go ahead,’ Dawlish said.

‘I’ve got it on the X-ray. It’s got electrical wiring in it so I want to go slowly, Mr Dawlish.’

‘Good Heavens yes,’ said Dawlish. ‘One doesn’t want the building blown to smithereens.’

‘Two doesn’t,’ said the duty bomber, and then he laughed and said it again, ‘two doesn’t.’

The small metal box that the Pike brothers had given me contained six fertile eggs and an electrical device that kept them at a constant temperature of 37° Centigrade. Each egg-shell had a wax-pencilled number, a filled notch and a puncture. Through the hyaline membrane of each egg a hypodermic needle had inserted a living virus. The eggs had been stolen from the Microbiological Research Establishment at Porton. The duty driver took them back to that quiet and picturesque corner of old England at five o’clock that morning, using a blanket and hot-water bottle to keep them warm and alive.

For my trip to Helsinki Dawlish and I put six medium-grade new-laid into the metal box. We got them from the canteen, but had a terrible job removing the little lion stamp-marks that guarantee purity.